Difference between revisions of "Quantum mechanics"

(The fundamental principle of quantum mechanics is that there is an uncertainty in the location of a subatomic particle until attention is focused on it by observing its location.) |

Conservative (Talk | contribs) m (Reverted edits by Thorin Oakenshield (talk) to last revision by DavidB4) |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''Quantum mechanics''' is the branch of [[physics]] that describes the behavior of systems on very small length and energy scales, such as those found in [[atom]]ic and subatomic interactions. | + | '''Quantum mechanics''' is the branch of [[physics]] that describes the behavior of systems on very small length and energy scales, such as those found in [[atom]]ic and subatomic interactions. The fundamental principle of quantum mechanics is that there is an uncertainty in the location of a subatomic particle until attention is focused on it by observing its location. This insight is essential for understanding certain concepts that [[classical physics]] cannot explain, such as the discrete nature of small-scale interactions, [[wave-particle duality]], the [[uncertainty principle]], and [[quantum entanglement]]. Quantum mechanics forms the basis for our understanding of many phenomena, including [[chemical reaction]]s and [[radioactive decay]], and is used by all [[computer]]s and electronic devices today. |

| − | The | + | '''''The order created by [[God]] is on a foundation of [[uncertainty]]'''''. The [[Book of Genesis]] explains that the world was an abyss of [[chaos]] at the moment of [[creation]]. Quantum mechanics is predicted in several additional respects by the [[Biblical scientific foreknowledge#Quantum mechanics|Biblical scientific foreknowledge]]. |

The name "Quantum Mechanics" comes from the idea that energy is transmitted in discrete quanta, and not continuous. Another historical name for "quantum mechanics" was "wave mechanics." | The name "Quantum Mechanics" comes from the idea that energy is transmitted in discrete quanta, and not continuous. Another historical name for "quantum mechanics" was "wave mechanics." | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | Until the early | + | Until the early 1900s, scientists believed that [[electron]]s and [[proton]]s were small discrete lumps. Thus, electrons would orbit the nucleus of an [[atom]] just as planets orbit the sun. The problem with this idea was that, according to classical [[electromagnetism]], the orbiting electron would emit energy as it orbited. This would cause it to lose rotational kinetic energy and orbit closer and closer to the proton, until it collapses into the proton! Since atoms are stable, this model could not be correct. |

The idea of "quanta", or discrete units, of energy was proposed by [[Max Planck]] in 1900, to explain the energy spectrum of [[black body]] radiation. He proposed that the energy of what we now call a photon is proportional to its frequency. In 1905, [[Albert Einstein]] also suggested that light is composed of discrete packets (''[[quanta]]'') in order to explain the [[photoelectric effect]]. | The idea of "quanta", or discrete units, of energy was proposed by [[Max Planck]] in 1900, to explain the energy spectrum of [[black body]] radiation. He proposed that the energy of what we now call a photon is proportional to its frequency. In 1905, [[Albert Einstein]] also suggested that light is composed of discrete packets (''[[quanta]]'') in order to explain the [[photoelectric effect]]. | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

In 1915, [[Niels Bohr]] applied this to the electron problem by proposing that [[angular momentum]] is also quantized - electrons can only orbit at certain locations, so they cannot spiral into the nucleus. While this model explained how atoms do not collapse, not even Bohr himself had any idea why. As Sir James Jeans remarked, the only justification for Bohr's theory was "the very weighty one of success".<ref name="VA">http://galileo.phys.virginia.edu/classes/252/Bohr_to_Waves/Bohr_to_Waves.html</ref> | In 1915, [[Niels Bohr]] applied this to the electron problem by proposing that [[angular momentum]] is also quantized - electrons can only orbit at certain locations, so they cannot spiral into the nucleus. While this model explained how atoms do not collapse, not even Bohr himself had any idea why. As Sir James Jeans remarked, the only justification for Bohr's theory was "the very weighty one of success".<ref name="VA">http://galileo.phys.virginia.edu/classes/252/Bohr_to_Waves/Bohr_to_Waves.html</ref> | ||

| − | It was Prince | + | It was Prince Louis de Broglie who explained Bohr's theory in 1924 by describing the electron as a wave with wavelength λ=[[Planck's Constant|h]]/[[momentum|p]]. Therefore, it would be logical that it could only orbit in orbits whose circumference is equal to an integer number of wavelengths. Thus, angular momentum is quantized as Bohr predicted, and atoms do not self-destruct.<ref name="VA" /> |

Eventually, the mathematical formalism that became known as quantum mechanics was developed in the 1920s and 1930s by [[John von Neumann]], [[Hermann Weyl]], and others, after [[Erwin Schrodinger]]'s discovery of wave mechanics and [[Werner Heisenberg]]'s discovery of matrix mechanics. | Eventually, the mathematical formalism that became known as quantum mechanics was developed in the 1920s and 1930s by [[John von Neumann]], [[Hermann Weyl]], and others, after [[Erwin Schrodinger]]'s discovery of wave mechanics and [[Werner Heisenberg]]'s discovery of matrix mechanics. | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

In quantum mechanics, it is meaningless to make absolute statements such as "the particle is here". This is a consequence of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle which (simply put) states, "particles move," in an apparently random manner. Thus, giving a definite position to a particle is meaningless. Instead, scientists use the particle's "position function," or "wave function," which gives the probability of a particle being at any point. As the function increases, the probability of finding the particle in that location increases. In the diagram, where the particle is free to move in 1 direction, we see that there is a region (close to the y-axis) where the particle is more likely to be found. However, we also notice that the wave function does not reach zero as it moves towards infinity in both directions. This means that there is a high likelihood of finding the particle around the center, but there is still a possibility that, if measured, the particle will be a long ways away. | In quantum mechanics, it is meaningless to make absolute statements such as "the particle is here". This is a consequence of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle which (simply put) states, "particles move," in an apparently random manner. Thus, giving a definite position to a particle is meaningless. Instead, scientists use the particle's "position function," or "wave function," which gives the probability of a particle being at any point. As the function increases, the probability of finding the particle in that location increases. In the diagram, where the particle is free to move in 1 direction, we see that there is a region (close to the y-axis) where the particle is more likely to be found. However, we also notice that the wave function does not reach zero as it moves towards infinity in both directions. This means that there is a high likelihood of finding the particle around the center, but there is still a possibility that, if measured, the particle will be a long ways away. | ||

| − | When the particle is actually observed to be in a specific location, its wave function is said to have "collapsed". This means that if it is again observed immediately the probability that it will be found near the original location is almost 1. However, if it is not immediately observed, the wave function reverts | + | When the particle is actually observed to be in a specific location, its wave function is said to have "collapsed". This means that if it is again observed immediately the probability that it will be found near the original location is almost 1. However, if it is not immediately observed, the wave function reverts to its original shape as expected. The collapsed wave function has a much narrower and sharper peak than the original wave function. |

Collapsing of the wave function is by no means magic. In can be intuitively understood as this: You find a particle at a particular spot; if you look again immediately, it's still in the same spot. | Collapsing of the wave function is by no means magic. In can be intuitively understood as this: You find a particle at a particular spot; if you look again immediately, it's still in the same spot. | ||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

===The uncertainty principle=== | ===The uncertainty principle=== | ||

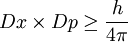

| − | As a result of the wave nature of a particle, neither position nor [[momentum]] of a particle can never be precisely known. Whenever its position is measured more accurately (beyond a certain limit), its momentum becomes less certain, and | + | As a result of the wave nature of a particle, neither position nor [[momentum]] of a particle can never be precisely known. Whenever its position is measured more accurately (beyond a certain limit), its momentum becomes less certain, and vice versa. Hence, there is an inherent uncertainty that prevents precisely measuring both the position and the momentum simultaneously. This is known as the [[Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle]]:<ref>http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/Hbase/uncer.html</ref> |

:<math> Dx \times Dp \ge \frac{h}{4\pi}</math> | :<math> Dx \times Dp \ge \frac{h}{4\pi}</math> | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

Several interpretations have been advanced to explain how wavefunctions "collapse" to yield the observable world we see. | Several interpretations have been advanced to explain how wavefunctions "collapse" to yield the observable world we see. | ||

| − | * The "hidden variable" interpretation<ref>http://www.reasons.org/resources/non-staff-papers/the-metaphysics-of-quantum-mechanics</ref> says that there is actually a [[determinism|deterministic]] way to predict where the wavefunction will collapse; we simply have not discovered it. [[ | + | * The "hidden variable" interpretation<ref>http://www.reasons.org/resources/non-staff-papers/the-metaphysics-of-quantum-mechanics</ref> says that there is actually a [[determinism|deterministic]] way to predict where the wavefunction will collapse; we simply have not discovered it. [[John von Neumann]] attempted to prove that there is no such way; however, [[John Stuart Bell]] pointed out an error in his proof. |

* The many-worlds interpretation says that each particle does show up at every possible location on its wavefunction; it simply does so in alternate universes. Thus, myriads of alternate universes are invisibly branching off of our universe every moment. | * The many-worlds interpretation says that each particle does show up at every possible location on its wavefunction; it simply does so in alternate universes. Thus, myriads of alternate universes are invisibly branching off of our universe every moment. | ||

| − | * The currently prevailing interpretation, the Copenhagen interpretation, states that the wavefunctions do ''not'' collapse until | + | * The currently prevailing interpretation, the Copenhagen interpretation, states that the wavefunctions do ''not'' collapse until the particle is observed at a certain location; until it is observed, it exists in a quantum indeterminate state of simultaneously being everywhere in the universe. However, [[Schrodinger]], with [[Schroedinger's Cat|his famous thought experiment]], raised the obvious question: who, or what, constitutes an observer? What distinguishes an observer from the system being observed? This distinction is highly complex, requiring the use of ''quantum decoherence theory'', parts of which are not entirely agreed upon. In particular, quantum decoherence theory posits the possibility of "weak measurements", which can indirectly provide "weak" information about a particle ''without'' collapsing it.<ref>http://quanta.ws/ojs/index.php/quanta/article/view/14/21</ref> |

==Applications== | ==Applications== | ||

An important aspect of Quantum Mechanics is the predictions it makes about the [[radioactive decay]] of [[isotopes]]. Radioactive decay processes, controlled by the wave equations, are random events. A radioactive atom has a certain probability of decaying per unit time. As a result, the decay results in an exponential decrease in the amount of isotope remaining in a given sample as a function of time. The characteristic time required for 1/2 of the original amount of isotope to decay is known as the "half-life" and can vary from quadrillionths of a second to quintillions of years. | An important aspect of Quantum Mechanics is the predictions it makes about the [[radioactive decay]] of [[isotopes]]. Radioactive decay processes, controlled by the wave equations, are random events. A radioactive atom has a certain probability of decaying per unit time. As a result, the decay results in an exponential decrease in the amount of isotope remaining in a given sample as a function of time. The characteristic time required for 1/2 of the original amount of isotope to decay is known as the "half-life" and can vary from quadrillionths of a second to quintillions of years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Quantum Mechanics has important applications in chemistry. The field of Theoretical Chemistry consists of using quantum mechanics to calculate atomic and molecular orbitals occupied by electrons. Quantum Mechanics also explain different spectroscopy used everyday to identify the composition of materials. | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 60: | Line 62: | ||

*[[Schrodinger equation]] | *[[Schrodinger equation]] | ||

*[[Heisenberg uncertainty principle]] | *[[Heisenberg uncertainty principle]] | ||

| − | + | ||

===Important contributors to quantum mechanics=== | ===Important contributors to quantum mechanics=== | ||

*[[Erwin Schrodinger]] | *[[Erwin Schrodinger]] | ||

| Line 69: | Line 71: | ||

*[[Max Planck]] | *[[Max Planck]] | ||

| − | ==External | + | ==External links== |

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

For an excellent discussion of quantum mechanics, see: | For an excellent discussion of quantum mechanics, see: | ||

| − | http://www.chemistry.ohio-state.edu/betha/qm/ | + | * http://www.chemistry.ohio-state.edu/betha/qm/ |

*[http://www.relativitycalculator.com/compton_effect.shtml The Compton Effect] | *[http://www.relativitycalculator.com/compton_effect.shtml The Compton Effect] | ||

Revision as of 00:35, September 9, 2016

Quantum mechanics is the branch of physics that describes the behavior of systems on very small length and energy scales, such as those found in atomic and subatomic interactions. The fundamental principle of quantum mechanics is that there is an uncertainty in the location of a subatomic particle until attention is focused on it by observing its location. This insight is essential for understanding certain concepts that classical physics cannot explain, such as the discrete nature of small-scale interactions, wave-particle duality, the uncertainty principle, and quantum entanglement. Quantum mechanics forms the basis for our understanding of many phenomena, including chemical reactions and radioactive decay, and is used by all computers and electronic devices today.

The order created by God is on a foundation of uncertainty. The Book of Genesis explains that the world was an abyss of chaos at the moment of creation. Quantum mechanics is predicted in several additional respects by the Biblical scientific foreknowledge.

The name "Quantum Mechanics" comes from the idea that energy is transmitted in discrete quanta, and not continuous. Another historical name for "quantum mechanics" was "wave mechanics."

Contents

History

Until the early 1900s, scientists believed that electrons and protons were small discrete lumps. Thus, electrons would orbit the nucleus of an atom just as planets orbit the sun. The problem with this idea was that, according to classical electromagnetism, the orbiting electron would emit energy as it orbited. This would cause it to lose rotational kinetic energy and orbit closer and closer to the proton, until it collapses into the proton! Since atoms are stable, this model could not be correct.

The idea of "quanta", or discrete units, of energy was proposed by Max Planck in 1900, to explain the energy spectrum of black body radiation. He proposed that the energy of what we now call a photon is proportional to its frequency. In 1905, Albert Einstein also suggested that light is composed of discrete packets (quanta) in order to explain the photoelectric effect.

In 1915, Niels Bohr applied this to the electron problem by proposing that angular momentum is also quantized - electrons can only orbit at certain locations, so they cannot spiral into the nucleus. While this model explained how atoms do not collapse, not even Bohr himself had any idea why. As Sir James Jeans remarked, the only justification for Bohr's theory was "the very weighty one of success".[1]

It was Prince Louis de Broglie who explained Bohr's theory in 1924 by describing the electron as a wave with wavelength λ=h/p. Therefore, it would be logical that it could only orbit in orbits whose circumference is equal to an integer number of wavelengths. Thus, angular momentum is quantized as Bohr predicted, and atoms do not self-destruct.[1]

Eventually, the mathematical formalism that became known as quantum mechanics was developed in the 1920s and 1930s by John von Neumann, Hermann Weyl, and others, after Erwin Schrodinger's discovery of wave mechanics and Werner Heisenberg's discovery of matrix mechanics.

The work of Tomonaga, Schwinger and Feynman in quantum electrodynamics led to the modern framework of quantum mechanics, currently applicable in quantum electrodynamics and quantum chromodynamics.

Principles

- Every system can be described by a wave function, which is generally a function of the position coordinates and time. All possible predictions of the physical properties of the system can be obtained from the wave function. The wave function can be obtained by solving the Schrodinger equation for the system.

- An observable is a property of the system which can be measured. In some systems, many observables can take only certain specific values.

- If we measure such an observable, generally the wave function does not predict exactly which value we will obtain. Instead, the wave function gives us the probability that a certain value will be obtained. After a measurement is made, the wave function is permanently changed in such a way that any successive measurement will certainly return the same value. This is called the collapse of the wave function.

Collapse of The Wave Function

In quantum mechanics, it is meaningless to make absolute statements such as "the particle is here". This is a consequence of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle which (simply put) states, "particles move," in an apparently random manner. Thus, giving a definite position to a particle is meaningless. Instead, scientists use the particle's "position function," or "wave function," which gives the probability of a particle being at any point. As the function increases, the probability of finding the particle in that location increases. In the diagram, where the particle is free to move in 1 direction, we see that there is a region (close to the y-axis) where the particle is more likely to be found. However, we also notice that the wave function does not reach zero as it moves towards infinity in both directions. This means that there is a high likelihood of finding the particle around the center, but there is still a possibility that, if measured, the particle will be a long ways away.

When the particle is actually observed to be in a specific location, its wave function is said to have "collapsed". This means that if it is again observed immediately the probability that it will be found near the original location is almost 1. However, if it is not immediately observed, the wave function reverts to its original shape as expected. The collapsed wave function has a much narrower and sharper peak than the original wave function.

Collapsing of the wave function is by no means magic. In can be intuitively understood as this: You find a particle at a particular spot; if you look again immediately, it's still in the same spot.

The uncertainty principle

As a result of the wave nature of a particle, neither position nor momentum of a particle can never be precisely known. Whenever its position is measured more accurately (beyond a certain limit), its momentum becomes less certain, and vice versa. Hence, there is an inherent uncertainty that prevents precisely measuring both the position and the momentum simultaneously. This is known as the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle:[2]

where:

- Dx = uncertainty in position

- Dp = uncertainty in momentum

- h = Planck's Constant

Interpretations

Several interpretations have been advanced to explain how wavefunctions "collapse" to yield the observable world we see.

- The "hidden variable" interpretation[3] says that there is actually a deterministic way to predict where the wavefunction will collapse; we simply have not discovered it. John von Neumann attempted to prove that there is no such way; however, John Stuart Bell pointed out an error in his proof.

- The many-worlds interpretation says that each particle does show up at every possible location on its wavefunction; it simply does so in alternate universes. Thus, myriads of alternate universes are invisibly branching off of our universe every moment.

- The currently prevailing interpretation, the Copenhagen interpretation, states that the wavefunctions do not collapse until the particle is observed at a certain location; until it is observed, it exists in a quantum indeterminate state of simultaneously being everywhere in the universe. However, Schrodinger, with his famous thought experiment, raised the obvious question: who, or what, constitutes an observer? What distinguishes an observer from the system being observed? This distinction is highly complex, requiring the use of quantum decoherence theory, parts of which are not entirely agreed upon. In particular, quantum decoherence theory posits the possibility of "weak measurements", which can indirectly provide "weak" information about a particle without collapsing it.[4]

Applications

An important aspect of Quantum Mechanics is the predictions it makes about the radioactive decay of isotopes. Radioactive decay processes, controlled by the wave equations, are random events. A radioactive atom has a certain probability of decaying per unit time. As a result, the decay results in an exponential decrease in the amount of isotope remaining in a given sample as a function of time. The characteristic time required for 1/2 of the original amount of isotope to decay is known as the "half-life" and can vary from quadrillionths of a second to quintillions of years.

Quantum Mechanics has important applications in chemistry. The field of Theoretical Chemistry consists of using quantum mechanics to calculate atomic and molecular orbitals occupied by electrons. Quantum Mechanics also explain different spectroscopy used everyday to identify the composition of materials.

See also

Concepts in quantum mechanics

Important contributors to quantum mechanics

External links

For an excellent discussion of quantum mechanics, see: