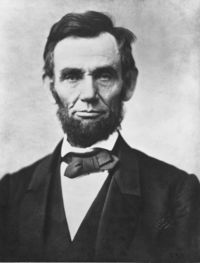

Abraham Lincoln

| Abraham Lincoln | |

|---|---|

| |

| 16th President of the United States | |

| Term of office March 4, 1861 - April 15, 1865 | |

| Political party | Republican |

| Vice Presidents | Hannibal Hamlin (1861-1865) Andrew Johnson (1865) |

| Preceded by | James Buchanan |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Born | February 12, 1809 Hardin County, Kentucky |

| Died | April 15, 1865 (aged 56) Washington, D.C. |

| Spouse | Mary Todd |

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, and a man who led the country through its darkest chapter, the American Civil War. His humble origins, from his birth in a Kentucky log cabin, his early life of poverty, through his struggle with life in a frontier society gave him an all-too human, and humane, personality, which he used to great effect in his law practice, his politics, and ultimately the presidency. And despite a severe lack of a formal education, Lincoln is the author of some of the most profound and eloquent writings ever to have come from the pen of an American.

Contents

Early life

“I was born Feb. 12, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky. My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguished families-- second families, perhaps I should say. My mother, who died in my tenth year, was of a family of the name of Hanks, some of whom now reside in Adams, and others in Macon Counties, Illinois.” [1]

Abraham Lincoln was born in a backwoods cabin some three miles south of Hodgenville, Kentucky. His father was Thomas Lincoln, who himself was a descendant of a weaver’s apprentice who had migrated to Massachusetts from England some years after the Mayflower landed. Thomas was a sturdy man, committed to pioneering in the new lands of Kentucky and Indiana, despite his lack of prosperity. He married Nancy Hanks on June 12, 1806, and together they had three children: Sarah, Abraham, and Thomas, who did not survive infancy. Young Abraham’s earliest memories of his days in Kentucky were his helping his father plant some seeds of corn and sunflower, and of a flood that washed them away.

In December 1816 Thomas had to pack up his family and leave for southwestern Indiana to avoid a lawsuit which had threatened him with a takeover of his property. There he built what was a “half-faced” camp, just a crude log structure with one side open to the elements, and there the family stayed as squatters on public land until Thomas had finished a permanent cabin, and later would buy the land outright on which it stood. Helping Thomas clear the land and plowing the fields was Abraham, who would also take care of the crops but developed a dislike for tasks which put additional food on the table, hunting and fishing. The poverty, Lincoln recalled, was “pretty pinching” at times, and by the age of nine he was a tall, lanky boy dressed rather ragged and unkempt.

Then the fall of 1818 brought the hardest blow: Nancy had died of the “milk sickness”, leaving Abraham without the mother whom he deeply loved. Some time later, Thomas had taken the buckboard and the mule, and left Abraham and Sarah on their own for two weeks; when he returned, he was with a new wife, Sarah Bush Johnson; she immediately made up for the absence of Nancy by replacing Abraham’s corn husk mattress with one of down, winning him over the first day. The new step-mother treated both children with an even hand (she herself was a widow with three children, whom she had brought), but she became very fond of Abraham, and he in turn was fond of her, referring to her as his “angel mother” for the rest of his life.

Education

Both of Abraham’s parents were nearly completely illiterate, and he himself had not much more than one year of formal education. When he did go to school, it was by “littles” – a little here, a little there – and he would call it “blab” school, which meant that they had to recite their lessons constantly due to lack of paper, pencils, and chalk. “Of course, when I came of age I did not know much. Still, somehow, I could read, write, and cipher to the rule of three; but that was all.”

His step-mother encouraged his reading as much as possible, and although Abraham did not have access to a large number of books, he would read as much of what was there, and read voraciously. He read John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Aesop’s Fables, Daniel DeFoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Parson Weems's Life and Memorable Actions of George Washington, Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and undoubtedly he read many times the only book his family actually owned, the Bible. He would walk for miles to borrow a book he heard about, and after his chores he would collapse into a heap in front of the fire and read for hours. He would say years later that his best friend was the man who let him borrow a book he hadn’t read yet.

The Rail-Splitter

The Lincolns moved to Illinois in March, 1830, with Abraham driving the team of oxen himself, a young man of 21, rawboned and lanky at six feet four inches tall. But the years working on the Indiana farm have also made him physically powerful, and on his arrival in Illinois he was soon to demonstrate the skill with which he could wield an axe, putting it to good use by clearing the trees and laying the fence on his father’s new farm; the speed with which he could take tree trunks and split them into the rails needed for the fencing just by using his axe earned him the nickname “rail-splitter.” He could make an axe flash and bite deep; one neighbor saying “He could sink an axe deeper into wood than any man I ever saw.” And after a good deal of chopping, he could take the axe by its handle and hold it straight out away from his body, without a single quiver. (Sandburg, pg. 14) Good-natured as well, he would make friends easily, despite his awkward-looking stride and backwoods language.

Soon, he signed on as a deckhand on a flatboat, and made a voyage down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. When he returned he settled in a small town on the Sangamon River called New Salem, working as a store keeper, surveyor, or a postmaster, the later of which allowed him to be the first to read the arriving newspapers. Then talk went about town of Lincoln’s utter honesty, how he would walk six miles to return a few cents to a customer he had accidentally overcharged, or the woman that had bought some tea, and having used the wrong weight for the purchase, Lincoln made the correction and walked the many miles to her house to ensure she got the right order (Sandburg, pp 24-25).

In 1832 he enlisted in the Black Hawk War, and was elected captain of his company, but the only fighting he admitted seeing action in was the “many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes.” After he was mustered out of his company, he aspired for the state legislature, losing the contest the first time he ran, then getting elected and re-elected several times afterward. He had briefly thought about practicing the trade of blacksmithing, but his craving of reading led him to law books, which caused some serious studying. Lincoln passed the bar in 1836, and began a new career practicing law.

Springfield

The following year he moved to the new state capital of Illinois, Springfield, becoming law partners with John T. Stuart, Stephan T. Logan, and finally William H. Herndon in 1844, who, although junior in age to Lincoln by a decade, made a good, balanced partner. Few records exist of their law business, and when they got paid for their services they split the cash, no matter who was paid. Lincoln would earn $1,200 - $1,500 annually within just a few years; by comparison circuit judges earned $750. But to earn it he kept busy and worked hard; often he would climb into his buggy and travel the circuit of neighboring counties and practice before the courts there. And often the cases he would be involved in were petty

Years before he had tried, and failed, to push legislation through the state assembly to have the Sangamon River made navigable to New Salem; by 1850 the railroads were bringing business and prosperity to Illinois, and Lincoln, by virtue of the ease the railroad made in traveling to his courts, profited more. He had served as a lobbyist for the Illinois Central Railroad, enabling it to get a state charter; he would defend the company against McClean County’s unsuccessful efforts to tax it. He handles cases for other railroads, banks, manufacturing, and other large companies in the state; he handled some patent suits and a few criminal trials. And he also saved the first bridge to cross the Mississippi River from demolition, when river interests demanded the bridge be taken down.

The moonlight murder

In Lincoln’s New Salem days he was introduced to the Clary’s Grove Boys, a group of rowdy men from that nearby town would come into New Salem to bully some of the male townsfolk. The leader of the group was Jack Armstrong, who’s challenge to wrestle the Salem men usually resulted in Armstrong throwing the unfortunate man to the ground in a very short time; when he saw Lincoln, Armstrong would dismiss the lanky young man as a pushover. It was when they fought that Armstrong discovered just how hard it was to throw Lincoln – in fact, it was impossible. The battle ended in a draw, and the good-natured Lincoln made a new friend. Armstrong would later be one of the men to elect Lincoln to lead the company of volunteers in the Black Hawk War.

In 1856, Jack Armstrong’s son, William (or “Duff”), was charged with murder. A witness had claimed that he had seen Duff and another kill a New Salem man late at night by the light of full moon. Lincoln pulled out an almanac and proved that the witness could not have seen anything at all, as the moon was at its quarter and had actually set over an hour before. Duff was acquitted, and Lincoln won the case.

Politics

Andrew Jackson, the hero of New Orleans in the War of 1812 and a Democrat from Tennessee, was in the White House when Lincoln first entered politics. He shared with Jackson the sympathies for the common man, but differed in the role of government as related to it; Jackson stated the government should be separated from the economic enterprise, while Lincoln was of the view that “the legitimate object of government is to do for a community of people whatever they need to have done, but cannot do at all, or cannot do so well, for themselves, in their separate and individual capacities.” Lincoln most associated himself with the Whig Party, as among their members Henry Clay and Daniel Webster both advocated a government should be encouraging business, and the development of the country to that end. It was an easy choice for Lincoln: he saw Illinois as needing such aid to improve the development of its own economy.

In the Illinois State Legislature Lincoln found that politics could be detrimental and harsh, as well as rewarding. An example of the former occurred in 1836, just as he gave a speech in support of his re-election. Democrat John Forquer, also seeking election, used his response and acid tounge to denounce him. "This young man needs to be taken down" he said, pointing to Lincoln, "and I'm afraid the task devolves upon me." The success of Forquer's speech convinced some of Lincoln's own allies that his career was over.

But when Lincoln rose to make his rebuttal, he thought of Forquer, and what he had done recently in conniving with President Jackson to change parties; in reward for doing so he was made Government Land Register with a $3,000 annual salary. Forquer was then able to construct a fine new house in Springfield, complete with a curiosity residents had heard about from science but had never seen before: a lightning rod. Before he entered the state house building that day, Lincoln spent a few minutes at Forquer's house staring at the thing, and having heard Forquer's speech later on, he thought of what he saw. Lincoln's reply was blistering, and sealed Forquer's fate.

- "Among other things he said, the gentleman commenced his speech by saying that 'this young man,' alluding to me, 'must be taken down.' I am not so young in years as I am in the tricks and the trades of a politician, but, live long or die young, I would rather die now than, like the gentleman, change my politics, and with the change receive an office worth $3,000 a year, and then feel obliged to erect a lightning-rod over my house to protect a guilty conscience from an offended God!" (Sandburg, pg.49)

Lincoln also proposed state funding to construct a network of roads, railroads, and canals. Both Whigs and Democrats would join in for the passing of this omnibus bill, but a business depression was created by the panic of 1837, and as a result most of the provisions in the bill were abandoned. 1837 was also marked by the murder of Elijah Lovejoy, a newspaperman from Alton who was killed by a mob due to his anti-slavery views. The legislature introduced resolutions defending Southern slavery while condemning abolitionist societies, as per the U.S. Constitution. In protest of the resolutions Lincoln, with a fellow legislator, drew up a declaration [2] which stated that slavery was “founded on both injustice and bad policy,” while also declaring that “the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its evils.”

He only served one term in the United States Congress, 1847 to 1849, during which time he did little on legislative matters. He did introduce a bill calling for a gradual emancipation of slaves within the District of Columbia, but since it hinged on the approval of the white citizens there, it only caused mild anger from abolitionists as well as slave holders, and was quietly dropped. His one main issue was over the Mexican War, in which he condemned the American entry into it on false pretenses, particularly blaming current president James K. Polk. He worked toward the nomination of Zachary Taylor for the presidency, and when Taylor had won, Lincoln expected to be rewarded with the job of land commissioner, but failed. He was voted out of office by his constituents, as they felt he was too critical of the war. Disillusioned, he left politics and reentered his law practice.

Return to politics

He stayed out for five years, winning several cases before the courts, then in 1854 he had read in the papers that Stephan A. Douglas, his political rival and Democratic senator from Illinois, had placed before Congress a bill which would reopen the territory of the Louisiana Purchase to slavery, as well as allow settlers in the Kansas and Nebraska territories to vote for themselves whether or not they wanted it, a concept which was called “popular sovereignty” by Douglas. The resulting Kansas-Nebraska Act would do nothing more than provoke violent opposition; a border war would result between Kansas and Missouri as both pro and anti-slavery forces would cause much bloodshed; and voters in the Old Northwest, Illinois among them, would react vehemently against it, resulting in the destruction of the Whigs as a political party, and the birth of the Republicans, of which Lincoln quickly became a member. The Dred Scott decision of 1856, in which a black man who sued for his freedom only to be told that he was never a citizen and had to remain a slave, only added more fuel to the fire, as the states were aligning slave versus free, North versus South.

As the leading member of the Republican Party in Illinois, Lincoln was nominated for the Senate seat held by Douglas at the Republican State Convention in Springfield on June 16, 1858. The acceptance speech he gave has been called the House Divided speech, after the opening lines, which were based upon Matthew 12:25:

- If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it. We are now far into the fifth year since a policy was initiated with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only not ceased, but has constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached and passed. "A house divided against itself cannot stand." I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved -- I do not expect the house to fall -- but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new -- North as well as South. [3]

August through October, 1858 saw seven Illinois towns witnessing the Lincoln-Douglas debates; Douglas the national figure defending the choice of voters whether to accept slavery or not, and the little-known Lincoln taking a stand against slavery on political, social, and moral grounds. Douglas never wavered from defending popular sovereignty, and he also played on the voters' fears of black integration. Stating blacks were inferior to whites, he appealed to racists by declaring that the government was "established upon the white basis. It was made by white men, for the benefit of white men." (TL 1, pg 106). Lincoln on the other hand knew Douglas was in a war of his own with President Franklin Buchanan's administration over acceptance of the Kansas constitution which barred slavery from the state, further alienating Southern Democratic support; the fear was that Douglas would be more appealing to moderate Republicans in the east. Lincoln's strategy therefore was to point out and use the vast difference between the moral indifference to slavery as embodied by Douglas's popular sovereignty, and the moral wrong that slavery actually was as embodied by Republican opposition to it. Douglas was, Lincoln insisted, a man who did not care whether slavery was "voted up or voted down." By his last debate, Lincoln would narrow the differences between himself and Douglas as the basic principle of right and wrong.

- "That is the real issue. That is the issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself shall be silent. It is the eternal struggle between these two principles -- right and wrong -- throughout the world. They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time; and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says, "You work and toil and earn bread, and I'll eat it." No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle." [4]

Douglas for his part knew how formidable his foe was, and declared that if he won, “it would be a hollow victory.” He did win, retaining his Senate seat, but by a narrow margin.

The presidency

- My friends, no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of the Divine Being who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail. Trusting in Him who can go with me, and remain with you, and be everywhere for good, let us confidently hope that all will yet be well. To His care commending you, as I hope in your prayers you will commend me, I bid you an affectionate farewell. Lincoln's Farewell Speech to the citizens of Springfield, February 11, 1861.

On May 18, 1860 at the Republican National Convention held in Chicago, Lincoln was nominated on the third ballot. He then set aside his law practice and gave full time to the direction of his campaign, with the object of first uniting the Republicans from anything with which the party could disagree over. The Democrats were already divided, having nominated Douglas in Baltimore on the Northern platform of popular sovereignty, and John C. Breckenridge who was elected on a platform of states’ rights and slavery by Southern Democrats. Lincoln won the election of 1860, winning a clear majority in popular votes as well as electoral votes, despite winning no votes in the South.

The state of South Carolina proclaimed its secession from the Union in December, 1860, soon after Lincoln’s victory. To try to prevent other states from following, compromises were hurriedly pushed through Congress, one of which, the Crittenden Amendment, guaranteed the existence of slavery in perpetuity where it already existed, and dividing the territories between slave and free; Lincoln, however, was opposed to it, as he believed that despite this slavery would still expand south of the U.S. border. Six more states seceded, joining with South Carolina to form the Confederate States of America.

A crisis was thus forced upon Lincoln before he even entered the White House. Fort Sumter, in South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor, was claimed by the Confederacy and ordered to be turned over; the commander, Major Robert Anderson, refused. Lincoln, still in Springfield, asked Winfield Scott, general in chief of the U.S. Army, to be prepared “to either hold, or retake, the forts, as the case may require, at, and after the inauguration.”

On the 4th of March, 1861, a few weeks after Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as president of the Confederacy, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the nation's 16th president. In his address he reiterated his stance, and what he believed the stance of the nation should be, namely non-interference with slavery where it existed, and preventing slavery to spread in the territories, and above all was his stand to preserve the Union. The substance of what he said was conciliatory, but it also mentioned the obvious

- "In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to "preserve, protect, and defend it." [5]

However, communications between the fort and Charleston broke down, and General P.G.T. Beauregard, believing Fort Sumter had a supply ship on the way, ordered the fort shelled on April 14, 1865. The Civil War had begun.

Civil War

Lincoln’s goal was to preserve the Union; he would have been happy to preserve the peace as well, but he was willing to engage in a war to preserve it as well, a war he thought would be short. After Fort Sumter he proclaimed a blockade of Southern ports and called for thousands of volunteers to enlist for ninety days. He also believed that an overland war was inevitable, and he ordered forces on a march on the Virginia front, resulting in the first great defeat for the Union at Bull Run (July 21, 1861). Shortly afterward, Lincoln issued a set of memorandums for the military, of which his basic thought was that armies in the field must advance concurrently and on several fronts.

Finding himself as the leader of a country now at war, Lincoln used a description of himself in which he let events control him, and then react to the problem. It was something of himself that was used with success as a politician. In this sense he was being practical, ready to employ an action or decision which would help the cause, and ready to abandon it and use another if the first failed. But his first insight with which he held fast to, that of taking the fight to the enemy’s army, failed many times when successive generals tried to take the fight to the enemy’s capitol and failed, or failed in following up on a rare victory. He had George McClellan on the Peninsula, but was beaten back during the Seven Days battles. His replacement, John Pope, lost in a repeat of Bull Run. McClellan was back again, winning a victory at Antietam, but failed to follow through in capturing the enemy’s army afterwards. Then Ambrose Burnside, followed by Joseph Hooker, led the Army of the Potomac to massive defeats at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, respectively. Then George Gordon Meade was put in, just in time for the Battle of Gettysburg; Meade would not finish off the enemy either. Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commented on the frequent changes in generals. “I’m afraid they’re going to find a general I cannot understand.”

Having seen what he done at Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga, Lincoln found the fighting general he was looking for in Ulysses S. Grant. In March 1864 he promoted Grant to lieutenant general and gave him command of all Federal armies. Grant would have his headquarters in the field with Meade’s Army of the Potomac, and his subordinates William T. Sherman, Philip Sheridan, and George H. Thomas would each lead an army to take the fight to the enemy. Halleck would be given a new title, chief of staff, and remain in Washington as the presidential liaison. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton would be responsible for the procurement of men and supplies. By this reorganization Lincoln created the structure of the high command in which all the energies of and resources of the country were mobilized into a grand strategy for the completion of the war. It was all the more remarkable as prior to 1861, he had no knowledge of military theory or affairs; he threw himself into studying the subject that by 1864, he was considered to be something of a military genius.

Personal life

Ann Rutledge played a part in stories as being the first woman Lincoln may have fallen in love with. However, evidence is scant, and what surviving letters and documents there are indicate they were close friends. She died in 1835 at the age of 22, and the entire community grieved with Lincoln.

The one true love of Lincoln’s life was a well-educated woman with a quick wit, Mary Todd, from a well-to-do family in Springfield. Lincoln endured a courtship that lasted two years (and was broken once), before they were married on November 4, 1842. Together they would have four boys: Robert Todd, Edward Baker (“Eddie”, who died at age 4), William Wallace (“Willie”), and Thomas (“Tad”). Willie and Tad were the first children in the White House, and the halls and gardens were filled with childish romps, especially from the rambunctious, uncontrollable Tad, who once took a group of office seekers there to see the president on a trip through a confusing maze of hanging laundry; drove a herd of goats inside; got into the attic and rang the servants’ bells for hours; and succeeded in getting his doll executed for sleeping on watch.

The Lincolns also had their share of quarrels, and stories passed through the years tended to exaggerate them, but existing letters between the two indicate they were like any other married couple. They were devoted to each other’s company, and when apart they missed each other. "I have fallen in love with her," Lincoln would write to a friend about Mary, "and have never fallen out." Mary did have fits of temper and a sense of insecurity; while in the White House she had spells of simple jealousy which she staged in front of guests; sometimes the scene would be quite embarrassing. She also rang up large bills for her personal wardrobe and redecorating the White House; Lincoln, when he found out one such bill which totaled near $20,000 and coupled with a request for Congress to appropriate the money needed to pay for it, displayed a rare occurrence of pure anger:

- "It would stink in the nostrils of the American people to have it said the President of the United States had approved a bill overrunning an appropriation of $20,000 for flub dubs, for this damned old house, when the soldiers cannot have blankets!" [6]

The early deaths of Eddie in 1850 and Willie in 1863 may have played a role in Mary’s eccentricity. Lincoln did what he could to support her, even pointing out the presence of a nearby building which housed a sanitarium, hinting that Mary could be placed there if she didn't control herself over Willie's death.

On slavery

In 1841, Lincoln had a flatboat trip down the Mississippi, and he saw sitting on board another boat a group of slaves chained together. He described the sight in a letter to Joshua Speed in 1855: “You may remember, as I well do, that from Louisville to the mouth of the Ohio there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border.”

Lincoln hated slavery. “I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself,” he declared. “I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world; enables the enemies of free institutions with plausibility to taunt us as hypocrites.” [7] In 1855, writing to his friend Joshua Speed, he recalled a steamboat trip the two had taken on the Ohio River14 years earlier. “You may remember, as I well do,” he said, “that from Louisville [Kentucky] to the mouth of the Ohio there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border.” [8]

Lincoln often penned fragments on slavery. He would begin it by starting a hypothetical vested interest in slavery, and end it with the only logical conclusion, that is was a great moral wrong.

- If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B.—why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A?

- You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.

- You do not mean color exactly? You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own.

- But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest; you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you. (Fragment on Slavery, April, 1854)

Lincoln was elected on a platform which pledged no interference with slavery where it had already existed, and he was hesitant to adopt an abolitionist policy. He was concerned about the reaction of the border states should such a policy be enacted. He was concerned about four million newly-freed blacks being incorporated into the country’s social, economic, and political life. Some individuals, such as General John C. Freemont, made it a point to proclaim freedom in districts which they had conquered; Lincoln revoked those proclamations. In a letter to Horace Greely, Lincoln plainly stated

- "My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that."

Lincoln was willing to play a major part in removing slavery altogether during the war. He first proposed an idea in which slaves were to be freed gradually by the actions of the states, with the federal government sharing the cost of compensation. None of the border states were willing to implement it, and no prominent African-American leader was willing to see newly-freed blacks sent to Africa, as part of the idea called for.

But with the victory at Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln brought out an idea which he read before his cabinet, that slaves held in the Confederate States were declared to be free. He would declare it formally with his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Although it did not include those areas under Union control, and officially it was a war measure, it had a great deal of significance as a symbol, and European countries who had toyed with the idea of recognizing the Confederacy abandoned it and supported the Union.

Lincoln also felt that the freed slaves would be put back in chains at war's end, as the Proclamation itself was not constitutional. But Lincoln was prepared for something else: he drafted the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which stated slavery was illegal except for crimes committed. He also urged the Republican Party to add the proposed amendment as a plank to the 1864 presidential campaign, stating slavery was the cause of the war, and that the Proclamation had aimed “a death blow at this gigantic evil;” only by a constitutional amendment could slavery be rendered extinct. After the election, Lincoln did not wait for the new Congress. He got the two-thirds needed for ratification before the year was over, and rejoiced when his state of Illinois led the way.

- "In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free - honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth. Other means may succeed; this could not fail. The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just - a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud, and God must forever bless." Annual Message to Congress, December 1, 1862.

Religion

Abraham Lincoln, like many other people of his day, believed that "Religion is a private affair between a man and his God." Doubts about Lincoln's faith have arisen mainly because he never officially joined a church, which his political opponents used sometimes to accuse him. He had a love of the Bible and memorized parts of the Bible. Lincoln said once that: "I doubt the possibility or propriety of settling the religion of Jesus Christ in the models of man-made creeds and dogmas. I cannot without mental reservations assent to long and complicated creeds and catechisms."

He also said on another occasion:

- "That I am not a member of any Christian church is true, but I have never denied the truth of the Scriptures, and I have never spoken with intentional disrespect of religion in general or of any denomination of Christians in particular."

He also made statements that suggest a strong faith, such as when his father was ill:

- "Tell father to remember to call upon and confide in our great, and good, and merciful Maker who will not turn away from him in any extremity. He notes the fall of a sparrow and numbers the hairs of our heads; and he will not forget the dying man who puts his trust in him. If it is to be his lot to go now, he will soon have a joyous meeting with many loved ones gone before; and where the rest of us, through the help of God, hope ere long to join them."

Rumors still circulate. Many Christians believe that he was a strong Christian. Others believe he was not one. Another opinion is that he became one while in office. After he was shot at Ford's theater two clergy claimed that he had made a secret trip from Washington to be baptized. Also a Roman Catholic Priest claimed that Lincoln received the sacrament of baptism in secret. Neither of these claims have any proof in White House records or his personal diary.[1]

Lincoln's style of writing

A White House visitor, Orville Browning, told Lincoln's personal secretary John Nicolay one day that he had spoke to Lincoln sometime in 1861 on the subject of slavery; that if the right thing about slavery wasn't done, God just couldn't be on the side of the Union. Browning remembered Lincoln's reply: "What if the Almighty takes a different view of slavery than we do?", and right then and there Browning realized that Lincoln had thought very deep on the subject, much deeper than Browning did. [9]

Lincoln was known to think long and deep on various topics, and often he would take notes, write them on little scraps of paper, and stuff them into his tall stovepipe hat for later use. When it was time for use, such as his "House Divided" speech, he pulled them out, laid them on a table, and would commence to writing. He would sift through the subject, adding this, removing that, and sometimes he would stand in his empty room and deliver it out loud to an imaginary audience, testing the effects of what he spoke, and altering it as needed. According to author Garry Wills, Lincoln brought to bear the rhetorical tone of the Greek Revival and Transcendental movements, in which spoken oratory was practiced in government and on the stage. The leading speakers of this time, and whom Lincoln looked upon, were Danial Webster and Henry Clay, both of the Senate, and Edward Everett, a speaker much in demand.

The training he had given himself also enabled him to write a simple letter or a speech on the spot. Words would flow clear when Lincoln wrote in his later years, and he didn't have to do twice one of his finest personal letters, one of consolation to Mrs. Bixby of Boston, who had lost five sons in the war.

- Executive Mansion,

- Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.

- Dear Madam,

- I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

- I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

- I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.

- Yours, very sincerely and respectfully,

- A. Lincoln

What many consider his masterpiece is the Gettysburg Address. Here Lincoln, going through perhaps a dozen writes and re-writes of what he had thought on the subject, entirely changed the meaning of the war itself in a mere 272 words, and in so doing, according to Wills, remaking America.

Politics in war

That there had to be a certain degree of support to win the war was a given, and Lincoln strove to have unity for that effort in the North. Politics was required, and Lincoln had a special knack for appealing to his fellows and talking to them at their own level and language. He would smooth over lingering differences, and held the loyalty of those who were antagonistic to one another.

But the Democrats remained strong, and frequently clashed. Its member included both war and peace Democrats; the peace side was called “Copperheads”, after the snake which strikes without warning while hidden. Lincoln tried conciliating with both, but with the latter he had to resort to arrest at times, most famously to an Ohio Congressman, Clement L. Valandigham, who was arrested after he had repeatedly exhorted soldiers to desert. He justified his actions on the grounds that the suspension of habeas corpus was necessary only in times of rebellion, insurrection, or when the public safety may require it, as stated in the Constitution; certainly the Civil War had met those specific conditions. Many would dissent, and openly criticize Lincoln for arbitrarily violating the Constitution that he had sworn to preserve. In response to the criticism in general, and the case of Valandigham in particular, Lincoln wrote:

- "Must I shoot a simple-minded soldier boy who deserts, while I must not touch a hair of a wiley agitator who induces him to desert? This is none the less injurious when effected by getting a father, or brother, or friend, into a public meeting, and there working upon his feeling, till he is persuaded to write the soldier boy, that he is fighting in a bad cause, for a wicked administration of a contemptable government, too weak to arrest and punish him if he shall desert. I think that in such a case, to silence the agitator, and save the boy, is not only constitutional, but, withal, a great mercy." [10]

Lincoln faced reelection against Democrat George McClellan in 1864, who promised a restoration of the Union, but waffled on many of its points, even abandoning the Democratic platform of armistice and peaceful separation. Lincoln was able to beat him in the election, assisted by the timely victories of Sheridan in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, and Sherman in Georgia. Overtures of peace from Confederates were not wholly rejected. On February 3, 1865, Lincoln met with Confederate commissioners, among them Vice President Alexander Stephens, on a steamship in Hampton Roads, Virginia. There would be peace, he insisted, if the South would quit the war, abandon slavery, and accept re-unification, and once these conditions were met he would gracious with pardons. But his terms satisfied neither the Confederacy nor the Radical Republicans in Congress. His postwar policy was one of compassion. As he explained to his top leaders on board a riverboat, the City Queen, he wanted peace above all else. His Second Inaugural Address expressed his point of healing the wounds caused by the war.

- With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

When asked specifically, he related the following, according to General Sherman, one of those present:

- Mr. Lincoln was full and frank in his conversation, assuring me that in his mind he was all ready for the civil reorganization of affairs at the South as soon as the war was over; and he distinctly authorized me to assure Governor Vance and the people of North Carolina that, as soon as the rebel armies laid down their arms, and resumed their civil pursuits, they would at once be guaranteed all their rights as citizens of a common country; and that to avoid anarchy the State governments then in existence, with their civil functionaries, would be recognized by him as the government de facto till Congress could provide others.

- I know, when I left him, that I was more than ever impressed by his kindly nature, his deep and earnest sympathy with the afflictions of the whole people, resulting from the war, and by the march of hostile armies through the South; and that his earnest desire seemed to be to end the war speedily, without more bloodshed or devastation, and to restore all the men of both sections to their homes. In the language of his second inaugural address, he seemed to have "charity for all, malice toward none," and, above all, an absolute faith in the courage, manliness, and integrity of the armies in the field. [11]

Final curtain

Lincoln received the news of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Virginia, on April 9, and he was called out to the balcony of the White House that night by a large crowd gathered in celebration. When asked to make a speech, Lincoln noticed a band among them, and made an unusual request.

- "I have always thought ‘Dixie’ one of the best tunes I have ever heard. Our adversaries over the way attempted to appropriate it, but I insisted that we fairly captured it. I presented it to the Attorney General, and he gave it as his legal opinion that it is our lawful prize. I now request the band to favor me with its performance."

He entered Richmond the following day, to the joyous delight of free blacks, who welcomed the arrival of "Father Abraham" as they called him, and he paid a visit to the Confederate White House, and sat at the desk of Jefferson Davis. The only thing he asked for was a glass of water.

Just four days later on April 14 he attended a play at Ford's Theater. It was called Our American Cousin, with well-known stage actress Laura Keane and comedian Harry Hawke in the title role. Unseen to the audience was another actor making his way quietly up the stairs to the president's private box, John Wilkes Booth, a Southern sympathizer who had hatched a conspiracy with a few others to kill the president and other leading officials. Booth entered the box, shot Lincoln in the head, stabbed a guest, and dropped to the stage, escaping behind the curtains. Taken across the street to a boarding house, the mortally-wounded Lincoln was laid across a small bed in humble surroundings, similar it seemed, to where he was born. He died at sunrise a few hours later.

"Now he belongs to the ages" Edwin Stanton was heard to say.

References

- McCollister, John C. God and the Oval Office, W Publishing Group, Nashville, Tennessee(2005)

- Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1954)

- Walsh, John E. Moonlight, St. Martin's Press, New York (2000)

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: the Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, Simon and Schuster, New York (2005)

- Hanchett, William. The Lincoln Murder Conspiracies, University of Illinois (1983)

- Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln, Jonathan Cafe (Random House), London (1995)

- Wills, Gary. Lincoln at Gettysburg: the Words that Remade America, Simon and Schuster, New York (1992)

- White, Ronald C. Jr. The Eloquent President: A Portrait of Lincoln Through His Words, Random House, New York (2005)

- Carwardine, Richard. Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power, Alfred A. Knopf, New York (2003)

- Time-Life Books The Civil War, vol. 1 (Brother Against Brother), Time Inc, New York (1983)

Links

- Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln

- Abraham Lincoln Online

- Lincoln Archive of original newspaper articles

- History Place: Lincoln timeline

- Lincoln's Home National Historic Site

- White House site; short bio on Lincoln

- Mr. Lincoln and Friends

- Declaration against slavery, Illinois State Legislature, March 3, 1837

- Lincoln's letter to Joshua Speed, August 24, 1855

- Speech in Peoria, Illinois, October 16, 1854

- Letter to Erastus Corning and Others, June 13, 1863, in which Lincoln explains his suspention of habeas corpus

- Memoirs of William T. Sherman