Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) was the most famous physicist of the 20th century. He was born in Ulm, in Württemberg, Germany in a Jewish family. During his stay at the Swiss Patent Office Einstein produced much of his remarkable work. In 1905 he obtained his doctor's degree. He won the Nobel Prize for his work on the photoelectric effect in 1921. [1] Einstein immigrated to the United States in the late 1930s to take the position of Professor of Theoretical Physics at Princeton; upon the urging of a colleague in physics, recommended that President Franklin D. Roosevelt develop an atomic bomb project. [2] He later regretted this and became a passionate pacifist. In 1952, he was offered the Presidency of Israel, but he turned it down. Einstein collaborated with Dr. Chaim Weizmann in establishing the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Albert Einstein died on April 18, 1955 at Princeton, New Jersey at the age of 76.

Contents

Writings

- Special Theory of Relativity (1905)

- General Theory of Relativity (1916)

- Relativity: The Special and the General Theory (translation), 1st ed. (1920)

- Vier Vorlesungen über Relativitätstheorie (1922)

- Investigations on Theory of Brownian Movement (1926)

- About Zionism (1930)

- Why War? (1933)

- The World As I See It (My Philosophy) (1934)

- The Evolution of Physics (1938) with Leopold Infeld

- Out of My Later Years (1950)

- Einleitende Bemerkungen uber Grundbergriffe (1953)

- The Meaning of Relativity, 3rd ed. (1950), 4th ed. (1953), 5th ed. (1956)

...the daily effort comes from no deliberate intention or program, but straight from the heart.

Honors

Einstein received honorary doctorate degrees in science, medicine and philosophy from many American and European universities.

He won the Nobel Prize in 1921 for his work on the photoelectric effect.

- "It strikes me as unfair, and even in bad taste, to select a few individuals for boundless admiration, attributing superhuman powers of mind and character to them. This has been my fate, and the contrast between the popular assessment of my powers and achievements and the reality is simply grotesque." [3]

Einstein told a friend in 1930, "To punish me for my contempt of authority, Fate has made me an authority myself." [3]

He gained the Copley Medal of the Royal Society of London in 1925 and the Franklin Medal of the Franklin Institute in 1935.

Einstein was offered the presidency of Israel in 1952 [4] but respectfully declined, stating he believed his life-long study of objective matters made him an inappropriate candidate for a position in politics; he was also strongly opposed to nationalism.

In 1999, he was named "Person of the Century" by Time magazine.

Einstein and the A-bomb

In 1939 research done by several leading scientists including Enrico Fermi regarding chain reactions of nuclear fission prompted Leo Szilard to persuade Einstein to write a letter to President Roosevelt [5], to warn the President about the possibility of nuclear weapons and that Nazi Germany had already taken an interest in this technology.

Einstein himself had never been involved in the Manhattan project. He was considered a security risk, as he was a member, sponsor, or affiliated with thirty-four communist fronts between 1937 and 1954.[6] Later he condemned the use of nuclear weapons.

Controversy surrounding his death

Dr. Thomas Stoltz Harvey, then a pathologist, performed the autopsy on Einstein in the Princeton Medical Center several hours after his death. Upon completion, Dr. Harvey removed the brain and eyes [7]. There is controversy about whether or not Harvey had consent from the Einstein family to remove the brain and keep it, though letters from Otto Nathan, executor of the Einstein estate, suggest that Harvey did indeed have permission to keep the brain, as long as research performed on it was only described in scientific journals.

The brain was photographed and sliced into 240 pieces in order to be preserved and further studied. Harvey hoped some uniqueness would be discovered that distinguished Einstein's brain as "genius".

Although he sent pieces away for further study, the bulk of the brain remained with Harvey for over 40 years. His once-ambitious plans for doing research on Einstein's brain were never actualized, though there were at least two controversial studies performed which suggested a physical reason for Einstein's intelligence. In 1996 Harvey entrusted Elliot Krauss, chief pathologist at the Princeton Medical Center, with the brain. The brain now sits in a secret location, possibly only a few feet away from where it was first removed from Einstein's head. Krauss loans out pieces of the brain for scientific research, but he is very discriminating in deciding who shall receive a piece. [8]

Religious views

There is some controversy surrounding the religion of Albert Einstein.

Walter Isaacson reports him shortly after his fiftieth birthday explaining his religious views to an interviewer in this manner:“I'm not an atheist. I don't think I can call myself a pantheist. The problem involved is too vast for our limited minds. We are in the position of a little child entering a huge library filled with books in many languages. The child knows someone must have written those books. It does not know how. It does not understand the languages in which they are written. The child dimly suspects a mysterious order in the arrangement of the books but doesn't know what it is. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of even the most intelligent human being toward God. We see the universe marvelously arranged and obeying certain laws but only dimly understand these laws." [9]

In the same interview, Einstein spoke of his feelings regarding Christianity:

"As a child I received instruction both in the Bible and in the Talmud. I am a Jew, but I am enthralled by the luminous figure of the Nazarene."

And when asked if he accepted the historical existence of Jesus, Einstein replied:

"Unquestionably! No one can read the Gospels without feeling the actual presence of Jesus. His personality pulsates in every word. No myth is filled with such life."

Einstein also said

"In view of such harmony in the cosmos which I, with my limited human mind, am able to recognize, there are yet people who say there is no God. But what makes me really angry is that they quote me for support of such views."[10],

"[The fanatical atheists] are like slaves who are still feeling the weight of their chains which they have thrown off after hard struggle. They are creatures who—in their grudge against the traditional 'opium of the people' [Karl Marx's oft-cited description of religion]—cannot bear the music of the spheres."[10]

"God does not play dice with the universe."[11]

and

"Science without religion is lame. Religion without science is blind" [12]

"The word god is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honourable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish. No interpretation no matter how subtle can (for me) change this."[13]

"It was, of course, a lie what you read about my religious convictions, a lie which is being systematically repeated. I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly. If something is in me which can be called religious then it is the unbounded admiration for the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal it."[14]

Taken as a whole, it appears Einstein rejected the literal stories of God's personal involvement with the Hebrews, but he did believe in the existence of a higher power as a metaphor for what we did not know about the universe.

Views on Judaism and Zionism

In 1920, in a letter to the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith, Einstein wrote

"I am neither a German citizen, nor is there in me anything that can be described as ‘Jewish faith.’ But I am happy to belong to the Jewish people, even if I do not consider them in any way God's elect."

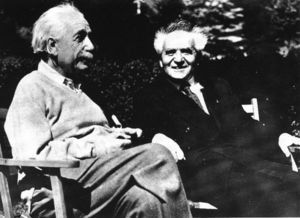

Einstein did not view fellow Jews as co-religionists, but as tribal companions. Einstein was made an honorary citizen of Tel Aviv during his visit in 1923. In 1952, Einstein was offered the position of president of Israel by the 1st prime minster of Israel David Ben-Gurion, but declined the offer. Before his death in 1955, Einstein wrote to the Zionist leader Kurt Blumenfeld:

"I thank you, even at this late hour, for having made me conscious of the Jewish soul."

Einstein willed that all his scholarly work be archived in Israel's Hebrew University after his death.

Einstein always expressed his anti-war views and staunchly opposed nationalism:

"He who joyfully marches to rank and file, has already earned my contempt. He has been given a large brain by mistake, since for him the spinal cord would surely suffice. This disgrace to civilization should be done away with at once. Heroism on command, how violently I hate all this, how despicable and ignoble war is; I would rather be torn to shreds than be a part of so a base of action. It is my conviction that killing under the cloak of war is nothing but an act of murder."

Einstein on Germany and the rise of Hitler

In 1944, in a message to a bulletin run by Polish Jews in New York, Einstein wrote

The Germans as an entire people are responsible for the mass murders and must be punished as a people if there is justice in the world and if the consciousness of collective responsibility in the nations is not to perish from the earth entirely. Behind the Nazi party stands the German people, who elected Hitler after he had in his book [Mein Kampf] and in his speeches made his shameful [genocidal] intentions clear beyond the possibility of misunderstanding.

Unsupported attributions

- Many ideas and quotes are falsely attributed to Einstein. He did not invent very much of we now call special relativity. The Principle of Relativity, that the law of physics should be the same in all inertial frames, had already been published before Einstein.[15] He did not discover the Lorentz transformation, or the Lorentz invariance of Maxwell's Equations for electromagnetism.[16] He was not the first to propose that the speed of light is constant for all observers, or that "the aether" is superfluous and not observable.[17] He was not the first to recognize and explain how special relativity causes an ambiguity in defining simultaneity.[18] He did not combine space and time into a four-dimensional spacetime in his special relativity papers until others had been doing it for a couple of years.

- Einstein did not invent the term "relativity theory", and did not even like the term. He called it the "so-called relativity theory" until 1911. Einstein did not banish the ether from Physics. In a 1920 lecture, he said, "More careful reflection teaches us, however, that the special theory of relativity does not compel us to deny æther."[19]

- Einstein was not the first to observe the equation E=mc2 as a consequence of special relativity,[20] or to foresee its application to nuclear binding energies or antimatter annihilation.

- Einstein only published faulty and incomplete proofs.[21]

- He did not foresee a nuclear chain reaction and had to be persuaded about the possibility of an atomic bomb.

- However, Einstein's interpretation of the E=mc2 equation was fairly popular.

- According to Einstein, a body losing energy through heat or radiation was losing mass.[22]

- Einstein did not originate the idea of using non-Euclidean geometry[23] metric tensors to reconcile gravity with special relativity.[24] It was not his idea to describe gravity in covariant equations, and he published papers supposedly showing that it was impossible.[25] He did not discover the Lagrangian formulation of general relativity, and was not the first to publish the field equations. He did not foresee the expansion of the universe (although this expansion is consistent with the field equations), the possibility of black holes, or dark energy.

- Einstein did not originate the idea that light is observable as particles. Max Planck published that a few years before Einstein, and received a Nobel prize for it.

- Einstein did not prove that matter was made of atoms. That had been known for a century when Einstein published his 1905 paper on Brownian motion.

- Einstein never developed a unified field theory of any significance. He published papers on quantum mechanics, but always insisted on a deterministic interpretation.

- Many quotes are falsely attributed to Einstein. Here are a few. "If the bee disappeared off the surface of the globe then man would only have four years of life left." "We use only 10% of our brains." "Evil is simply the absence of God." "Originality is the art of concealing your sources."

Quotes

Here are some quotes that have been attributed to Einstein, but which have not been verified.

- The difference between stupidity and genius is that genius has its limits.[26]

- Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning. [27]

- "Whoever is careless with the truth in small matters cannot be trusted with important matters." [28]

External links

- Relativity Science Calculator - e=mc2 derivation

- "The Nobel Prize in Physics, 1921" (2014). Nobelprize.org.

- Einstein, Albert (June 30, 1905). "On the electrodynamics of moving bodies". Translated in Perrett, Wilfred and Jeffery, George B. (1923), The Principle of Relativity: A Collection of Original Memoirs on the Special and General Theory of Relativity (London: Methuen), pp. 35-65. Translation of Das Relativatsprinzip (1922, Leipzig [Germany]: Teubner), 4th ed. Retrieved from Fourmilab [Switzerland] website.

- Einstein, Albert (September 27, 1905). "Does the inertia of a body depend on its energy-content?". Translated in Perrett, Wilfrid and Jeffery, George B. (1923), The Principle of Relativity (London: Methuen), pp. 67-71. Translation of Das Relativatsprinzip (1922, Leipzig [Germany]: Teubner), 4th ed. Retrieved from Fourmilab [Switzerland] website.

- Paterniti, Michael (2000). Driving Mr. Albert: A Trip Across America With Einstein's Brain (New York, NY: Random House).

- "Collected Quotes from Albert Einstein" [1]

References

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics, 1921" (2014). Nobelprize.org. Retrieved on January 23, 2015.

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (August 2, 1939). "Letter to F. D. Roosevelt, President of the United States". www.dannen.com. Retrieved from "Leo Szilard Online: Einstein's Letter to Roosevelt, August 2, 1939" on January 23, 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mallove, Eugene F., Sc. D. (July-August 2001). "The Einstein myths—of space, time and aether". Infinite Energy Magazine, iss. 38. Retrieved from Infinite Energy website on January 25, 2015.

- ↑ Küpper, Hans-Josef (2004 or bef.). "President of the State of Israel". Albert Einstein in the world wide web. Retrieved on January 25, 2015.

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (August 2, 1939). "Letter to F. D. Roosevelt, President of the United States". Hypertextbook/E-World. Retrieved on January 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Albert Einstein" (2004). Federal Bureau of Investigation website. Retrieved from August 10, 2004 archive at Internet Archive on January 25, 2015.

- ↑ "The long strange journey of Einstein's brain" (April 18, 2005). Review and excerpt from Burrell, Brian (2005), Postcards from the Brain Museum. National Public Radio website. Retrieved on January 25, 2015.

- ↑ Abraham, Carolyn (2001). Possessing Genius (U.K.: Icon Books), 2005 edition.

- ↑ Isaacson, Walter (April 27, 2007). "Einstein and the mind of God". Washington Post.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Jammer, Max (1999). Einstein and Religion (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

- ↑ Et Cetera (1943), p. 61. Retrieved from GoogleBooks archive on January 26, 2015.

- ↑ Isaacson, Walter (2007). Einstein: His Life and Universe (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster), p. 390. Retrieved from GoogleBooks archive on January 26, 2015.

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (January 3, 1954). Excerpt of "Letter to Eric Gutkind". Excerpt retrieved from Randerson, James (May 13, 2008), "Childish superstition: Einstein's letter makes view of religion relatively clear", Theguardian website [U.K.] on January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (March 24, 1954). Letter from Albert Einstein - The Human Side (1979), selected and edited by Dukas, Helen and Hoffman, Banesh (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

- ↑ Logunov, A. A. (2005). Henry Poincaré and Relativity Theory. Retrieved from Cornell University arXiv.org archive on January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Macrossan, Michael N. (1986) "A note on relativity before Einstein". British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, vol. 37, no. 2:, pp. 232-234. Retrieved from University of Queensland [Australia]/UQ eSpace archive on January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Rothman, Tony (March-April 2006). "Lost in Einstein's shadow". American Scientist, vol. 94, no. 2, p. 112. Retrieved on January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Fric, Jacques (June 2003). "Henri Poincaré: A decisive contribution to Special Relativity, the short story". www.everythingimportant.org. Retrieved on January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Quoted in Tipler, Frank J., astrophysicist of Tulane University (October 26, 2008). "The Obama-Tribe 'Curvature of constitutional space' paper is crackpot physics". Social Science Research Network website. Retrieved on January 31, 2015.

- ↑ Henri Poincaré published it in 1900. Hermann, Robert A. (January 1, 2004). "E=mc2 is not Einstein's discovery". Retrieved from December 17, 2008 archive at Internet Archive on January 24, 2015.

- ↑ Multiple references:

- Ohanian, Hans C. (September 2008). Einstein's Mistakes: The Human Failings of Genius. Retrieved on January 31, 2015.

- "Einstein's 23 biggest mistakes" (September 1, 2008). Discover magazine website. Retrieved on January 31, 2015.

- ↑ Multiple references:

- Einstein, Albert (September 27, 1905). "Ist die Trägheit eines Körpers von dessen Energieinhalt abhängig?", Annalen der Physik, vol. 18, pp. 639–643. Retrieved from December 17, 2008 Internet Archive archive of University of Augsburg/Annalen der Physik website on January 31, 2015.

- English translation: Einstein, Albert (September 27, 1905). Hypertext of "Does the inertia of a body depend on its energy-content?". Translated in Perrett, Wilfrid and Jeffery, George B. (1923), The Principle of Relativity (London: Methuen), pp. 67-71. Hypertext retrieved from Fourmilab [Switzerland] website on January 31, 2015.

- ↑ His friend Paul Ehrenfest pointed out the need for curved space. Kaku, Michio (2014). "Albert Einstein". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved on February 1, 2015.

- ↑ Walter, Scott (2006). "Breaking in the 4-vectors: the four-dimensional movement in gravitation, 1905–1910". University of Nancy 2 [France]/Department of Philosophy/Scott Walter website. Retrieved from December 5, 2006 archive at Internet Archive on February 1, 2015.

- ↑ Norton, John D. (March 1993). "General covariance and the foundation of general relativity: eight decades of dispute". Reports on Progress in Physics, no. 56, pp. 791-858. Retrieved from University of Pittsburgh/John D. Norton website on February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Applewhite, Ashton, et al. (2003). And I Quote: The Definitive Collection of Quotes, Sayings, and Jokes for the Contemporary Speechmaker (New York: St. Martin's), rev. ed., p. 146. Retrieved from GoogleBooks on February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Darbellay, Frédéric et al. (2008). A Vision of Transdisciplinarity: Laying Foundations for a World Knowledge Dialogue (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), p. xix. Retrived from GoogleBooks on February 2, 2015.

- ↑ Feld, Bernard T. (1979). "Einstein and the Politics of Nuclear Weapons". Albert Einstein: Historical and Cultural Perspectives: The Centennial (1982), edited by Holton, Gerald James and Elkana, Yehuda (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), p. 388. Retrieved from GoogleBooks on February 3, 2015.