Difference between revisions of "America First Committee"

(fairer language) |

DavidB4-bot (Talk | contribs) (clean up & uniformity) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

The committee collapsed after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. It had been thoroughly discredited and most of the activists reversed positions. Interventionists for years attacked their opponents as "America Firsters". | The committee collapsed after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. It had been thoroughly discredited and most of the activists reversed positions. Interventionists for years attacked their opponents as "America Firsters". | ||

| − | In recent years [[Pat Buchanan]] has supported a new political party, the America First Party, that is organized in several states. Critics of Buchanan, who favors non-interventionism in foreign policy, have said that he has justified anti-semitism or Naziism in so doing. Some historians have rejected his interpretations of the 1940s and wondered about his treatment of Nazi foreign policy.<ref> See Alan J. Levine, "Buchanan's Flawed History of World War II," ''World and I,'' Vol. 15, August 2000 [http://www.questia.com/read/5002356598?title=Buchanan's%20Flawed%20History%20of%20World%20War%20Ii online edition]</ref> | + | In recent years [[Pat Buchanan]] has supported a new political party, the America First Party, that is organized in several states. Critics of Buchanan, who favors non-interventionism in foreign policy, have said that he has justified anti-semitism or Naziism in so doing. Some historians have rejected his interpretations of the 1940s and wondered about his treatment of Nazi foreign policy.<ref>See Alan J. Levine, "Buchanan's Flawed History of World War II," ''World and I,'' Vol. 15, August 2000 [http://www.questia.com/read/5002356598?title=Buchanan's%20Flawed%20History%20of%20World%20War%20Ii online edition]</ref> |

[[File:Go-war1940.jpg|thumb|350px|Approximate positions on war of major players; America First would be at the very top]] | [[File:Go-war1940.jpg|thumb|350px|Approximate positions on war of major players; America First would be at the very top]] | ||

==Debate on war== | ==Debate on war== | ||

| − | The debate on America's role in World War II, which began in September 1939, split the country in very complex fashion. Both parties split into "interventionists" and "isolationists." The conservatives split on the issue, and so did liberals. The America First movement gained support from both parties, and from liberals and conservatives. For example, prominent liberal members included Montana Senator [[Burton K. Wheeler]], North Dakota Senator [[Gerald P. Nye]], and [[Socialist Party ]] leader [[Norman Thomas]]. Many people sympathized with the movement without joining. The many student chapters included future celebrities, such as author [[Gore Vidal]] (a student at Phillips Exeter Academy), and future presidents Kennedy at Harvard and [[Gerald R. Ford]], at Yale. | + | The debate on America's role in World War II, which began in September 1939, split the country in very complex fashion. Both parties split into "interventionists" and "isolationists." The conservatives split on the issue, and so did liberals. The America First movement gained support from both parties, and from liberals and conservatives. For example, prominent liberal members included Montana Senator [[Burton K. Wheeler]], North Dakota Senator [[Gerald P. Nye]], and [[Socialist Party]] leader [[Norman Thomas]]. Many people sympathized with the movement without joining. The many student chapters included future celebrities, such as author [[Gore Vidal]] (a student at Phillips Exeter Academy), and future presidents Kennedy at Harvard and [[Gerald R. Ford]], at Yale. |

The most prominent member was aviator [[Charles Lindbergh]]. | The most prominent member was aviator [[Charles Lindbergh]]. | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

At its peak, America First may have had 800,000 members in 650 chapters, located mostly in a 300 mile radius of Chicago. It claimed 135,000 members in 60 chapters in Illinois, its strongest state.<ref>Schneider p 198</ref> Fundraising drives produced about $370,000 from some 25,000 contributors. Nearly half came from a few millionaires such as [[William H. Regnery]], [[H. Smith Richardson]] of the [[Vick Chemical Company]], General [[Robert E. Wood]] of Sears-Roebuck, [[Sterling Morton]] of [[Morton Salt Company]], publisher [[Joseph M. Patterson]] (New York ''Daily News'') and his cousin publisher [[Robert R. McCormick]] (''[[Chicago Tribune]]''). Future President [[John F. Kennedy]], then a student, sent a contribution, with a note saying "What you are doing is vital." | At its peak, America First may have had 800,000 members in 650 chapters, located mostly in a 300 mile radius of Chicago. It claimed 135,000 members in 60 chapters in Illinois, its strongest state.<ref>Schneider p 198</ref> Fundraising drives produced about $370,000 from some 25,000 contributors. Nearly half came from a few millionaires such as [[William H. Regnery]], [[H. Smith Richardson]] of the [[Vick Chemical Company]], General [[Robert E. Wood]] of Sears-Roebuck, [[Sterling Morton]] of [[Morton Salt Company]], publisher [[Joseph M. Patterson]] (New York ''Daily News'') and his cousin publisher [[Robert R. McCormick]] (''[[Chicago Tribune]]''). Future President [[John F. Kennedy]], then a student, sent a contribution, with a note saying "What you are doing is vital." | ||

| − | The movement was quite weak in the South, where both liberals and conservatives (and whites and blacks) supported FDR's foreign policy. America First did try to organize local chapters in the South, sponsor noninterventionist rallies, distribute pamphlets and solicit cash. None of the chapters became effective units and no major rallies were held in the South.<ref> See Wayne S. Cole, "America First and the South, 1940-1941." ''Journal of Southern History'' 1956 22(1): 36-47. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2955258 in JSTOR]</ref> | + | The movement was quite weak in the South, where both liberals and conservatives (and whites and blacks) supported FDR's foreign policy. America First did try to organize local chapters in the South, sponsor noninterventionist rallies, distribute pamphlets and solicit cash. None of the chapters became effective units and no major rallies were held in the South.<ref>See Wayne S. Cole, "America First and the South, 1940-1941." ''Journal of Southern History'' 1956 22(1): 36-47. [http://www.jstor.org/stable/2955258 in JSTOR]</ref> |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

* Doenecke, Justus D. ''The Battle Against Intervention, 1939-1941'' (1997), includes short narrative and primary documents; by a leading conservative historian | * Doenecke, Justus D. ''The Battle Against Intervention, 1939-1941'' (1997), includes short narrative and primary documents; by a leading conservative historian | ||

** Doenecke, Justus D. ''Storm on the Horizon: The Challenge to American Intervention, 1939-1941'' (2000). | ** Doenecke, Justus D. ''Storm on the Horizon: The Challenge to American Intervention, 1939-1941'' (2000). | ||

| − | ** Doenecke, Justus D. "American Isolationism, 1939-1941" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Summer/Fall 1982, 6(3), pp. | + | ** Doenecke, Justus D. "American Isolationism, 1939-1941" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Summer/Fall 1982, 6(3), pp. 201–216. [http://www.mises.org/journals/jls/6_3/6_3_1.pdf online version] |

| − | ** Doenecke, Justus D. "Explaining the Antiwar Movement, 1939-1941: The Next Assignment" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Winter 1986, 8(1), pp. | + | ** Doenecke, Justus D. "Explaining the Antiwar Movement, 1939-1941: The Next Assignment" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Winter 1986, 8(1), pp. 139–162. [http://www.mises.org/journals/jls/8_1/8_1_10.pdf online version] |

| − | ** Doenecke, Justus D. "Literature of Isolationism, 1972-1983: A Bibliographic Guide" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Spring 1983, 7(1), pp. | + | ** Doenecke, Justus D. "Literature of Isolationism, 1972-1983: A Bibliographic Guide" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Spring 1983, 7(1), pp. 157–184. [http://www.mises.org/journals/jls/7_1/7_1_10.pdf online version] |

| − | ** Doenecke, Justus D. "Anti-Interventionism of Herbert Hoover" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Summer 1987, 8(2), pp. | + | ** Doenecke, Justus D. "Anti-Interventionism of Herbert Hoover" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Summer 1987, 8(2), pp. 311–340. [http://www.mises.org/journals/jls/8_2/8_2_10.pdf online version] |

* Gordon, David. ''America First: the Anti-War Movement, Charles Lindbergh and the Second World War, 1940-1941''; [http://libraryautomation.com/nymas/americafirst.html presentation] to The [[New York Military Affairs Symposium]] in 2003 | * Gordon, David. ''America First: the Anti-War Movement, Charles Lindbergh and the Second World War, 1940-1941''; [http://libraryautomation.com/nymas/americafirst.html presentation] to The [[New York Military Affairs Symposium]] in 2003 | ||

* Jonas, Manfred. ''Isolationism in America, 1935-1941'' (1966). | * Jonas, Manfred. ''Isolationism in America, 1935-1941'' (1966). | ||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

* Parmet, Herbert S., and Marie B. Hecht; ''Never Again: A President Runs for a Third Term'' 1968. | * Parmet, Herbert S., and Marie B. Hecht; ''Never Again: A President Runs for a Third Term'' 1968. | ||

* [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=105486029 Schneider, James C. ''Should America Go to War? The Debate over Foreign Policy in Chicago, 1939-1941'' (1989)] | * [http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=105486029 Schneider, James C. ''Should America Go to War? The Debate over Foreign Policy in Chicago, 1939-1941'' (1989)] | ||

| − | * [http://www.questia.com/library/history/military-history/world-war-ii/world-war-ii-u-s-neutrality.jsp online books on U.S. Neutrality before World War II | + | * [http://www.questia.com/library/history/military-history/world-war-ii/world-war-ii-u-s-neutrality.jsp online books on U.S. Neutrality before World War II] |

===Primary sources=== | ===Primary sources=== | ||

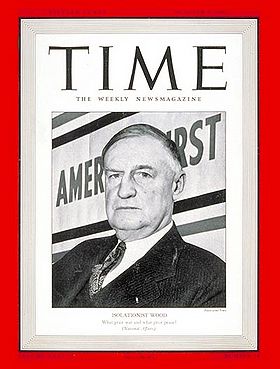

*[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,790233,00.html "Follow What Leader?" in ''Time'' Oct. 6, 1941 online] | *[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,790233,00.html "Follow What Leader?" in ''Time'' Oct. 6, 1941 online] | ||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

| − | [[Category: World War II]] | + | [[Category:World War II]] |

[[Category:United States Political Organizations]] | [[Category:United States Political Organizations]] | ||

Revision as of 05:04, June 27, 2016

The American First Committee was an "isolationist" organization that opposed United States involvement in World War II. It was highly visible in 1940-41, but failed to stop President Franklin D. Roosevelt from forming an informal alliance with Britain,, or stop Congress from passing legislation to aid Britain and Russia fight Nazi Germany. It concentrated almost exclusively on Europe; most members favored a hard line against Japan, even at the cost of war.

The committee collapsed after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. It had been thoroughly discredited and most of the activists reversed positions. Interventionists for years attacked their opponents as "America Firsters".

In recent years Pat Buchanan has supported a new political party, the America First Party, that is organized in several states. Critics of Buchanan, who favors non-interventionism in foreign policy, have said that he has justified anti-semitism or Naziism in so doing. Some historians have rejected his interpretations of the 1940s and wondered about his treatment of Nazi foreign policy.[1]

Contents

Debate on war

The debate on America's role in World War II, which began in September 1939, split the country in very complex fashion. Both parties split into "interventionists" and "isolationists." The conservatives split on the issue, and so did liberals. The America First movement gained support from both parties, and from liberals and conservatives. For example, prominent liberal members included Montana Senator Burton K. Wheeler, North Dakota Senator Gerald P. Nye, and Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas. Many people sympathized with the movement without joining. The many student chapters included future celebrities, such as author Gore Vidal (a student at Phillips Exeter Academy), and future presidents Kennedy at Harvard and Gerald R. Ford, at Yale.

The most prominent member was aviator Charles Lindbergh.

America First had four basic policies: the AFC advocated four basic assumptions:

- The United States must build an impregnable defense for America.

- No foreign power, nor group of powers, can successfully attack a prepared America.

- American democracy can be preserved only by keeping out of the European war.

- "Aid short of war" weakens national defense at home and threatens to involve America in war abroad.

The center was in Chicago, where the national headquarters was established.

Lindbergh

On June 20, 1940 Lindbergh spoke to a rally in Los Angeles billed as "Peace and Preparedness Mass Meeting". He attacked movements that he perceived as leading America into the war. He proclaimed that the United States was in a position that made it virtually impregnable and he pointed out that when interventionists said "the defense of England" they really meant "defeat of Germany." The rhetoric escalated in Lindbergh's famous speech in Des Moines, Iowa, on September 11, 1941. he identified the forces pulling America into the war as the British, the Roosevelt administration, and the Jews. While he expressed sympathy for the plight of the Jews in Germany, he argued that America's entry into the war would serve them little better. He said in part:

- It is not difficult to understand why Jewish people desire the overthrow of Nazi Germany. The persecution they suffered in Germany would be sufficient to make bitter enemies of any race. No person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution the Jewish race suffered in Germany. But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy, both for us and for them.

- Instead of agitating for war the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way, for they will be among the first to feel its consequences. Tolerance is a virtue that depends upon peace and strength. History shows that it cannot survive war and devastation. A few farsighted Jewish people realize this and stand opposed to intervention. But the majority still do not. Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government.[2]

Supporters

At its peak, America First may have had 800,000 members in 650 chapters, located mostly in a 300 mile radius of Chicago. It claimed 135,000 members in 60 chapters in Illinois, its strongest state.[3] Fundraising drives produced about $370,000 from some 25,000 contributors. Nearly half came from a few millionaires such as William H. Regnery, H. Smith Richardson of the Vick Chemical Company, General Robert E. Wood of Sears-Roebuck, Sterling Morton of Morton Salt Company, publisher Joseph M. Patterson (New York Daily News) and his cousin publisher Robert R. McCormick (Chicago Tribune). Future President John F. Kennedy, then a student, sent a contribution, with a note saying "What you are doing is vital."

The movement was quite weak in the South, where both liberals and conservatives (and whites and blacks) supported FDR's foreign policy. America First did try to organize local chapters in the South, sponsor noninterventionist rallies, distribute pamphlets and solicit cash. None of the chapters became effective units and no major rallies were held in the South.[4]

See also

- Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, the chief interventionist group

Bibliography

- Cole, Wayne S. Charles A. Lindbergh and the Battle against American Intervention in World War II (1974)

- Cole, Wayne S. America First: The Battle against Intervention, 1940-41 (1953)

- Doenecke, Justus D. The Battle Against Intervention, 1939-1941 (1997), includes short narrative and primary documents; by a leading conservative historian

- Doenecke, Justus D. Storm on the Horizon: The Challenge to American Intervention, 1939-1941 (2000).

- Doenecke, Justus D. "American Isolationism, 1939-1941" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Summer/Fall 1982, 6(3), pp. 201–216. online version

- Doenecke, Justus D. "Explaining the Antiwar Movement, 1939-1941: The Next Assignment" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Winter 1986, 8(1), pp. 139–162. online version

- Doenecke, Justus D. "Literature of Isolationism, 1972-1983: A Bibliographic Guide" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Spring 1983, 7(1), pp. 157–184. online version

- Doenecke, Justus D. "Anti-Interventionism of Herbert Hoover" Journal of Libertarian Studies, Summer 1987, 8(2), pp. 311–340. online version

- Gordon, David. America First: the Anti-War Movement, Charles Lindbergh and the Second World War, 1940-1941; presentation to The New York Military Affairs Symposium in 2003

- Jonas, Manfred. Isolationism in America, 1935-1941 (1966).

- S. Everett Gleason and William L. Langer; The Undeclared War, 1940-1941 1953 Policy toward war in Europe; pro FDR

- Kauffman, Bill, America First! Its History, Culture, and Politics (1995) ISBN 0-87975-956-9

- Parmet, Herbert S., and Marie B. Hecht; Never Again: A President Runs for a Third Term 1968.

- Schneider, James C. Should America Go to War? The Debate over Foreign Policy in Chicago, 1939-1941 (1989)

- online books on U.S. Neutrality before World War II