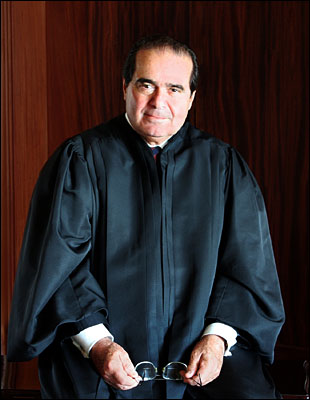

Antonin Scalia

Antonin "Nino" Scalia (b. 1936) joined the U.S. Supreme Court as an Associate Justice in 1986, and quickly became its most outspoken conservative jurist. He filled a vacancy created by the retirement of Chief Justice Warren Burger and nomination of Associate Justice William Rehnquist to become Chief Justice. President Ronald Reagan nominated Scalia at the same time that he nominated Rehnquist for Chief Justice, and Democrats in the U.S. Senate focused all their opposition on the Rehnquist nomination. Scalia was confirmed by unanimous vote, while Rehnquist was confirmed over substantial opposition.

Justice Scalia embraces a judicial philosophy of "textualism" or "original meaning" in interpreting the U.S. Constitution and federal statutes. He opposes speculation about the "intent" of the drafters or supporters of language that the Court must interpret. In speeches and legal writings, Justice Scalia emphasizes the "Rule of Law."[1].

Justice Scalia is easily the most outspoken member of the Court, and has been for two decades. He once quipped to the media, "Ah yes, esteemed jurist by day, man about town by night."[2] Sometimes Scalia's public commentary causes problems for himself, as when pro se litigant Dr. Michael Newdow successfully filed a motion forcing Justice Scalia's recusal of himself from Newdow's challenge to the Pledge of Allegiance.[3]

Justice Scalia is best known for his dissents, when his colorful and forceful style highlights weaknesses in his colleagues decisions. He lambasts the notion of an "evolving" Constitution, which other justices have used to justify decisions not grounded in the pure text of the Constitution (see Responsive interpretation). For example, when the Court held that the Constitution prohibits imposing the death penalty for any crime committed by someone under 18 years of age, Scalia was scathing in dissent:[4]

- In urging approval of a constitution that gave life-tenured judges the power to nullify laws enacted by the people's representatives, Alexander Hamilton assured the citizens of New York that there was little risk in this, since "[t]he judiciary . . . ha[s] neither FORCE nor WILL but merely judgment." The Federalist No. 78, p 465 (C. Rossiter ed. 1961). But Hamilton had in mind a traditional judiciary, "bound down by strict rules and precedents which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them." Bound down, indeed. What a mockery today's opinion makes of Hamilton's expectation, announcing the Court's conclusion that the meaning of our Constitution has changed over the past 15 years--not, mind you, that this Court's decision 15 years ago was wrong, but that the Constitution has changed. The Court reaches this implausible result by purporting to advert, not to the original meaning of the Eighth Amendment, but to "the evolving standards of decency," of our national society.

Justice Scalia has been less successful in forging majorities of his own on the Court, and has rarely written an important majority opinion for the Court. This may have been be due to the tendency for Chief Justice Rehnquist to assign key decisions to himself to draft.[5] Chief Justice John Roberts, who replaced Rehnquist, also seems to be keeping the key decisions for himself to write.[6]

References

- ↑ Scalia, "The Rule of Law as a Law of Rules," 56 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1175

- ↑ http://www.oyez.org/justices/antonin_scalia/

- ↑ supreme.lp.findlaw.com/supreme_court/briefs/02-1624/03-7.recuse.pdf

- ↑ Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551, 607-08 (2005) (Scalia, J., dissenting) (citations omitted. emphasis added)

- ↑ See, e.g., key 5-4 opinions written by Chief Justice Rehnquist in United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 (2000) (invaliding federal law over domestic violence based on federalism); Boy Scouts of Am. v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000) (holding that the Boy Scouts have a constitutional right not to allow openly homosexual scout leaders).

- ↑ Rumsfeld v. Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights, Inc., 547 U.S. 47 (2006)