Difference between revisions of "Atlas Shrugged"

(→Characters) |

(→Characters) |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

* The United States government | * The United States government | ||

** Executive Branch | ** Executive Branch | ||

| − | *** [[Mr. Thompson]], | + | *** [[Mr. Thompson]], Head of State |

*** [[Cuffy Meigs]], Director of Unification (Railroad Unification Plan) | *** [[Cuffy Meigs]], Director of Unification (Railroad Unification Plan) | ||

*** Charles "Chick" Morrison, Secretary of Morale Conditioning (i.e., Secretary of [[Propaganda]]) | *** Charles "Chick" Morrison, Secretary of Morale Conditioning (i.e., Secretary of [[Propaganda]]) | ||

*** "Tinky" Holloway, another senior administration official, portfolio unclear | *** "Tinky" Holloway, another senior administration official, portfolio unclear | ||

| − | ** The | + | ** The unicameral Legislature |

| − | *** Kip Chalmers, a candidate for the [[ | + | *** Kip Chalmers, a candidate for the Legislature from [[California]] |

**** Emma Chalmers, his mother, who conceives her own government program after her son dies | **** Emma Chalmers, his mother, who conceives her own government program after her son dies | ||

** Bureau of Economic Planning and Natural Resources | ** Bureau of Economic Planning and Natural Resources | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

** Andrew Stockton, a foundry operator and maker of coal furnaces | ** Andrew Stockton, a foundry operator and maker of coal furnaces | ||

** [[Ellis Wyatt]], President, Wyatt Oil Company | ** [[Ellis Wyatt]], President, Wyatt Oil Company | ||

| − | ** [[Quentin Daniels]], | + | ** [[Quentin Daniels]], a physicist who tries to reverse-engineer an electrostatic motor from a ruined prototype |

* Two notorious men to watch: | * Two notorious men to watch: | ||

Revision as of 18:27, March 24, 2012

Atlas Shrugged is a novel by Ayn Rand, first published in 1957 in the United States. It was partially an allegory to promote the author's philosophy of Objectivism, and initially intended to suggest that pure reason ought to be rated superior to emotion. The plot concerns the crumbling of the United States economy due to collectivism and altruism, which Rand considered detrimental to society, and the identity of John Galt, the mysterious protagonist of the story, a man whose name is spoken chiefly in slang.

Contents

History and development

Thematic Development

Ayn Rand would later say that she had in mind to write a novel on the theme of the tension between the mind and the heart, and the inherent superiority of reason to emotion.[1] In 1943, while she was considering how she could develop this theme, she had a conversation with her friend Isobel Paterson.[2] Paterson suggested that Ayn Rand ought to write a non-fiction expository book on her philosophy, a thing that Rand did not wish to write. Paterson then said that her readers "needed" such a work. Rand became incensed at this mode of expression, and replied:

| “ | Oh, they do? What if I went on strike? What if all the creative minds of the world went on strike? That would make a good novel. | ” |

Rand finished her conversation with Paterson. And then her husband, Frank O'Connor, who had been listening to her side of the conversation, said to her, "You know, it would make a good novel."[2]

This was only the beginning, of course, for now Rand turned her full attention to the thing that she would later describe as the novel's primary theme: the role of the mind in man's existence. She asked herself what would happen to any society if "the creative minds of the world went on strike," which is to say, withdrew their talents from the world.[1] She then asked herself what would drive them to call such a strike. This process carried through to the development of all the various heroes, villains, and anti-villains in the story.

In addition to these themes, Rand expounded on a theme that one might describe as "the fallacy of the mind-body dichotomy." Rand attacked this apparent split between mind and body in two contexts, each based on a fallacious notion:

- That sexual feelings were inherently dishonorable and distasteful and therefore not only immoral, but amoral—and thus a man's choice of a sexual partner could never be a moral one.

- That the best exercise of the mind was in "pure" or abstract scientific research and not in the practical application of science to real human needs and desires.

Character Development

The Ayn Rand Institute suggests that the two heroes of the novel were Dagny Taggart and John Galt.[1] This is not actually in accord with literary convention. Dagny Taggart certainly is the novel's heroine, but the other hero is Henry Rearden. They are heroes precisely because each must make a life-altering re-evaluation and decision in order to serve the causes that motivate them, a thing that John Galt does not do.

John Galt is actually an anti-villain: one who pursues the cause of justice with the same single-mindedness of purpose with which a classical villain might pursue his own greed or an insane desire for vengeance. His major decision to call the great strike is a decision he makes before, not during, the time frame of the novel's action.

Rand's character development decisions sometimes reflected the philosophical points she wished to make, and at other times reflected her almost free association between those characters and certain real-life counterparts. Some of her choices might seem bizarre; for example, her archetype for Mr. Thompson was President Harry S. Truman, and that for Robert Stadler was J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the Manhattan Project.

Rand herself was the archetype of the novel's heroine, Dagny Taggart. Rand later said that Dagny Taggart was herself at the top of her form at all times.

Characters

- The Taggart Transcontinental Railroad

- James Taggart, President

- Dagny Taggart, his sister, Vice-President in Charge of Operations

- Edwin "Eddie" Willers, Miss Taggart's special assistant

- A track walker in the New York City terminal, unidentified until near the end

- Clifton Locey, a temporary VP-Operations

- David Mitchum, superintendent, Colorado Division

- William "Bill" Brent, a dispatcher

- Various conductors, brakemen, track walkers, etc.

- Rearden Steel

- Henry "Hank" Rearden, founder and President

- Lillian Rearden, his wife

- Philip Rearden, his ne'er-do-well brother

- Henry Rearden's mother

- The Wet Nurse, aka "Non-Absolute," a government bureaucrat who has a change of heart and dies trying to protect Rearden from a staged riot at the mill

- Gwen Ives, his secretary

- Mills superintendent, infirmary physician, and various millworkers

- Associated Steel

- Orren Boyle, President

- Twentieth-Century Motor Company

- Gerald "Jed" Starnes, President (deceased)

- His children:

- Gerald Starnes, Jr.

- Eric Starnes

- Ivy Starnes

- William Hastings, former chief design engineer (deceased)

- Jeff Allen, former shop foreman

- Amalgamated Labor of America

- Fred Kinnan, President

- The United States government

- Executive Branch

- Mr. Thompson, Head of State

- Cuffy Meigs, Director of Unification (Railroad Unification Plan)

- Charles "Chick" Morrison, Secretary of Morale Conditioning (i.e., Secretary of Propaganda)

- "Tinky" Holloway, another senior administration official, portfolio unclear

- The unicameral Legislature

- Kip Chalmers, a candidate for the Legislature from California

- Emma Chalmers, his mother, who conceives her own government program after her son dies

- Kip Chalmers, a candidate for the Legislature from California

- Bureau of Economic Planning and Natural Resources

- Wesley Mouch, Senior Co-ordinator (formerly the Washington lobbyist for Rearden Steel)

- Eugene Lawson, former President, Community National Bank, Rome, Wisconsin

- State Science Institute

- Robert Stadler, PhD, Director (formerly Chairman, Department of Physics, Patrick Henry University)

- Floyd Ferris, PhD, Associate Director

- Dr. Potter, a representative

- Executive Branch

- Various "vanished" or "vanishing" persons:

- Hugh Akston, PhD, former Chairman, Department of Philosophy, Patrick Henry University

- Kenneth Dannager, President, Dannager Coal Company

- Richard Halley, composer

- Lawrence Hammond, President, Hammond Car Company

- Owen Kellogg, former railroad executive in Dagny Taggart's department

- Kay Ludlow, a stage actress

- Michael "Midas" Mulligan, a banker

- Judge Narragansett

- Andrew Stockton, a foundry operator and maker of coal furnaces

- Ellis Wyatt, President, Wyatt Oil Company

- Quentin Daniels, a physicist who tries to reverse-engineer an electrostatic motor from a ruined prototype

- Two notorious men to watch:

- Francisco Domingo Carlos Andres Sebastián d'Anconia, current head of D'Anconia Copper SA of the Republic (later "People's State") of Argentina, who has developed a reputation as a playboy

- Ragnar Danneskjöld, a privateer, i.e. a "pirate."

- The man behind the apparent economic collapse and raft of "vanishings":

- John Galt, known only by the appearance of his name in a question—"Who is John Galt?"—asked sometimes in cynicism, sometimes in fear.

Plot

Non-contradiction

Dagny Taggart is an unusual woman. Though she is named after the wife of the founder of the Taggart Transcontinental Railroad (Nathanial Taggart, whose statue still stands in the New York Terminal), her brother once said that she reminded people more of Nat Taggart than of his wife—a comparison that she has always taken as a compliment. Her brother is the current president of the railroad, but Dagny, as Vice-President of Operations, is the one who keeps the trains running, and they both know it.

Henry Rearden is more than the head of the most successful steelmaker in America. He has invented a new alloy that, like steel, contains iron, but also contains copper. This metal is so much stronger (yet lighter) than steel that it actually has its own name: Rearden Metal.

But for all his success, Henry Rearden is unhappy at home. His wife does not begin to appreciate the significance of his work, and neither does anyone else in his immediate family.

Henry Rearden and Dagny Taggart meet when Dagny has embarked on a great project: to reclaim a railroad line that has fallen into shocking disrepair, and to lay rail made of the new Rearden Metal. While James Taggart prefers to use political lobbying to further the interests of the railroad, Dagny is determined to lay rail and make trains run the old-fashioned way. She and Rearden both face political obtacles—Dagny must overcome the rumors that Rearden Metal is not as claimed, and Henry Rearden finds his business hampered by legislation. But Dagny also faces another obstacle: nearly every good businessman to whom she sends a request-for-proposal suddenly quits business and vanishes, leaving no forwarding address or even any practical trace.

While this is happening, Dagny reduces service and moves rolling stock out of a line that extends into Mexico, because she anticipates that the Mexican government, or "People's State," will nationalize it. As she predicted, Mexico does nationalize the line, and the copper mines that it was intended to serve—but then the Mexicans discover that they have nationalized a worthless mine. What shocks Dagny more is that the mines were a project of an old childhood friend of hers: Francisco d'Anconia, head of D'Anconia Copper SA of Argentina. Dagny goes to see Francisco and demand an explanation. He offers none beyond this cryptic clue: that "contradictions do not exist," and that if she finds his behavior strange, she should "check [her] premises."

Despite all the obstacles, Dagny and Henry complete their project, and together they ride in the first locomotive to make a run on the new line (which also contains a new bridge made entirely of Rearden Metal). After that, they begin an often tempestuous romance.

Shortly after that, they drive together to a deserted factory town in Wisconsin, to see a factory that had once had a branch line from Taggart Transcontinental, until Dagny had ordered it discontinued. There Dagny finds the remains of a prototype of an electrostatic motor, one that runs on static electricity from the atmosphere. Together Dagny and Rearden try to track down the engineer who built this motor, but no one seems to remember anything about the motor. They remember much, however, about the Twentieth Century Motor Company and its decline. Dagny interviews several people, including two of the surviving children of Gerald "Jed" Starnes, the founder of the Twentieth Century, and Hugh Akston, once a philosophy professor and now a short-order cook.

Then Congress passes a set of new laws that will make doing business next to impossible for some of the customers on the refurbished railroad line. Those laws prompt most of those companies to join the ever-swelling ranks of businessmen who have quit and vanished. One of them—Ellis Wyatt, who extracts oil from shale in the mountains of Colorado—not only quits and vanishes, but also burns his oil fields and leaves a sign on the border of his property:

| “ | I am leaving it as I found it. Take over. It's yours. | ” |

The fire that he lights, thereafter known as Wyatt's Torch, will not be extinguished until long after the action in the novel is finished.

Either-or

The United States government is doing more than pass bad laws. Robert Stadler, director of the State Science Institute, tries to call his associate director on the carpet with regard to a book that tells its readers that they ought to stop thinking or even believe that they are thinking. Stadler also wants to know about a mysterious "Project X" that has a large budget but no apparent accountability. The associate refuses to answer, and one gathers very quickly that Dr. Stadler is a mere figurehead, chosen for his reputation, and that Dr. Floyd Ferris, the nominal associate, is the real director.

Meanwhile, Dagny and Rearden each continue as best as he or she can. Rearden must accept a low-level bureaucrat, or "Deputy Director for Distribution," to ensure that he never delivers more than anyone's "fair share" of Rearden Metal to any one customer—except those who can wangle special exceptions from Washington. The workers at the plant call this man the Wet Nurse; Rearden takes to calling him Non-Absolute because his favorite thing to say seems to be that "there are no absolutes." Dagny, for her part, hires a consulting engineer, one Quentin Daniels, to attempt to reverse-engineer the mysterious electrostatic motor that she discovered at the Twentieth Century plant. Ironically, Daniels comes recommended by Robert Stadler, though Stadler said that a mind that could produce a working electrostatic motor belonged in "pure," that is to say abstract, research and not in something as "vulgar" as a commercial enterprise.

Politics aside, Dagny is now convinced that some person or persons unknown is/are deliberately destroying the American economy by encouraging its most talented movers to quit and vanish. When Ken Dannager abruptly retires from the coal business, after being indicted for exceeding his "fair share" of Rearden Metal, he lets slip that he had had a visitor who was that very "destroyer." Dannager gives her one clue: that his visitor had told him that he had a right to exist. He also predicts that Dagny will someday join him.

Rearden goes to trial for his part in the fair-share violation—though the real reason is that Rearden refused to fulfill an order of Rearden Metal for the State Science Institute for the benefit of Project X, a project the nature of which Rearden has no clue. At the trial, Rearden defiantly tells the court that he will not honor the proceedings, nor recognize the court's authority. The court imposes a $5000 fine and then suspends the sentence, a spectacle that provokes laughter among the spectators.

Rearden plans another "violation" of the Fair Share Directive, by ordering enough copper to pour several thousand tons of rail made of Rearden Metal. The problem: he orders it from D'Anconia Copper, only to read that the notorious pirate Ragnar Danneskjold has attacked a convoy of d'Anconia ships and sent them, with their loads, to the bottom of the Caribbean. In fact, Ragnar Danneskjold by now "owns" the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico, and no government relief ship, nor any vessel of d'Anconia Copper, is safe from him. But though he seizes the relief cargoes, he never takes the copper. No one can figure out why.

The political situation continues to worsen. The apparent culmination is Directive 10-289, an attempt to "freeze" the economy in place and forbid people to quit or change their jobs. In response, Dagny announces her resignation and retires to a summer home in the Berkshire Mountains. Francisco d'Anconia visits her there. And now he reveals that the "playboy" persona that he has cultivated over the last twelve years has been a careful disguise for his real activity: to destroy his old family firm, so that when the Argentine government nationalizes it, as he predicts that they inevitably will, they will have nothing to work with.

Their conversation is interrupted by a shocking report: a catastrophic explosion involving the Taggart Comet (the premiere coast-to-coast express) and a special ammunition train has collapsed the eight-mile Taggart Tunnel through the Rocky Mountains. Against Francisco d'Anconia's fervent protests, Dagny returns to work.

Dagny Taggart is not Francisco d'Anconia's only target. He has been trying to cultivate a relationship with Henry Rearden, not knowing that he and Rearden are in essence pursuing the same woman, i.e. Dagny. When the two men discover their mutual interest in her, Rearden strikes d'Anconia, but d'Anconia refuses to strike back. In fact, d'Anconia's interest in Rearden is far more important than any such consideration: he is trying to induce Rearden to quit his business and vanish, by reminding Rearden that he is no longer his own master and is serving the interests of those who must ultimately destroy him.

Rearden has his own crisis with Directive 10-289. Among its provisions is one that sets aside all intellectual property law and forces everyone to release all inventions, writings, etc. into the public domain. Rearden is forced to release Rearden Metal into the public domain by a threat of blackmail in connection with the driving trip that he and Dagny took to Wisconsin. But the first company to attempt to make Rearden Metal without Rearden's help (Orren Boyle's Associated Steel company) has its blast furnaces shelled to bits by long-range naval guns, after a voice identifying itself as that of Ragnar Danneskjold warns all the workers to evacuate. As Rearden walks home one evening, brooding on his political reverses, Ragnar Danneskjold actually confronts him on the road and hands him an ingot of gold, which he describes as "a small payment on a very large debt" which is "the money that was taken from you by force."

On the night following her return to work, Dagny Taggart travels westward in her private railcar, attached to the Taggart Comet which must now pass through a new route. She is trying to reach Quentin Daniels, because his last communication indicated that he might be ripe for quitting and vanishing. When a conductor finds a stowaway (Jeff Allen) on board, Dagny abruptly invites him to stay with her. She learns that he was once a skilled lathe operator who once worked for twenty years at the Twentieth Century Motor Company, until "the owner of the plant died, and the heirs that took it over, ran it into the ground." From him she obtains a description of the way the heirs destroyed the company: by introducing an explicitly Marxian system of compensation, or "distribution of alms." Then he provides the first clue she has had in a long time to the raft of vanishings of gifted individuals: that on the day of the inauguration of that plan, a young engineer had stood up and announced his intention to "stop the motor of the world." The engineer's name was John Galt—a name she is used to hearing as a slang phrase, but a name that for the first time she realizes belongs to a real person.

That night the train stops. It has become a "frozen train," whose conductor, trainmen, and crew have simply stopped and abandoned. Dagny appoints the former lathe operator to take charge of the restive passengers while she walks forward to try to get another crew out to move the train. Then she travels on her own, eventually renting a private plane to continue her search for Quentin Daniels.

When she discovers that Quentin Daniels has climbed into another aircraft that has only recently taken off, Dagny takes off in pursuit. As she follows the fleeing craft, that craft suddenly vanishes into thin air over a valley that looks entirely rocky. Not believing that a plane could simply disappear, she starts to descend. Then a bright flash of light blinds her, and when she recovers her eyesight, she realizes that her plane's engine has stopped and that she is almost in free fall. Defiant to the end, she fights to regain some semblance of control before she crashes.

A is A

The first person she sees on awakening is the face of a smiling man, a man of commanding presence. He shocks her by telling her his name: John Galt. Gently he picks her up from the green grass onto which she has fallen, and she barely perceives the wreck of her plane (badly damaged, but still reparable) before he carries her into the center of a town bustling with activity. She is surprised to see several men whom she knows from her list of the "vanished ones," including Michael "Midas" Mulligan, famous for vanishing and orchestrating a "controlled run" on his own bank. Those men speak to Mr. Galt in a curious code, using the word scab to describe her.

She is also told the secret of the seclusion of the valley: a screen of "refractor rays" that create a mirror in the sky for any passing aircraft, at an altitude of 8700 feet (700 feet above the altitude of the valley). Dagny Taggart is the first pilot brave (or foolhardy) enough to descend to that altitude, and the rays destroyed the electronic systems and shut down the aircraft's motor, causing the crash.

John Galt takes her to his house, and gives her a room he describes as "the room I never meant for you to occupy." The wall of that room is filled with short messages of encouragement, signed by the vanished ones, including Ellis Wyatt, Ken Danneger, and others. Later that evening, she attends a party at Mulligan's house. There the vanished ones, and John Galt, bluntly tell her their secret:

| “ | We are on strike. | ” |

Galt explains that the strike began with him, and continued with Francisco d'Anconia and Ragnar Danneskjold, then with Professor Hugh Akston, his former (now-deceased) boss William Hastings, and Midas Mulligan. Mulligan owns the valley, originally his private retreat and now a thriving economic center. The explanations solve the mystery of the vanishings, all right—but then Galt informs her that she must take time to decide whether to join this community.

Dagny receives an even greater shock the next day when Ragnar Danneskjold comes calling and describes the true intent of his privateering activities: to seize government "humanitarian" cargoes, sell the goods for gold, deposit the gold with Midas Mulligan's bank, and have the gold credited to various accounts in the names of the vanished ones and of prospects like Dagny herself, and Henry Rearden. Simply put, Danneskjold proposes to refund all income taxes paid by the vanished ones over the previous twelve years—the length of time that people have been vanishing. After Danneskjold leaves, Galt informs her that she must stay in the valley until the end of June, and must pay her way while there. She agrees—by hiring on as his personal cook and housemaid. For reasons that are not clear to her at all, the prospect provokes Galt to a belly laugh.

She remains in the secluded town—a town known as "Mulligan's Valley" to Galt and "Galt's Gulch" to every other inhabitant—for a month. During that time she observes a copper mine that Francisco has started in the side of one of the mountains. She at first proposes to build a railroad to carry the copper to the valley, but then despairs of laying such a short line and "abandon[ing] a transcontinental system." At the end of a month, she is not prepared to give up that system, and John Galt reluctantly takes her out of the valley and leaves her at the nearest airport.

When she returns, she finds that James Taggart has brokered a cynical deal called the "Railroad Unification Plan," under which all the railroads "pool" their resources and receive revenue according to the track they own (productive or not). She comments drily that that situation cannot last, but throws herself into the apparent mystery of frequent train wrecks.

One event that she has not witnessed is the actual demonstration of "Project X," which turns out to be a sonic weapon that can flatten any desired target within a very long range. Robert Stadler does attend the demonstration, and Floyd Ferris actually hands him a speech to deliver on that occasion.

Dagny is asked to speak at a special radio show to celebrate the "generosity" shown by Rearden when he signed the release of Rearden Metal into the public domain. (Signature or no, no one else dares attempt to make Rearden Metal without Rearden, for fear that Ragnar Danneskjold will blow up their furnaces as he did Orren Boyle's furnaces.) Dagny shocks her audience and the engineers by telling them the real reason for Rearden's action: that she had been his mistress, and that the governmental authorities had used that fact as blackmail. Rearden, noting her use of the pluperfect tense, acknowledges that he has lost her affections to another man, and is astonished to find that that other man is the mysterious John Galt.

Toward the end of summer, the Chilean government announces its intention to nationalize the D'Anconia Copper company. The legislative session for passing the nationalization act is set for September 2. But as the speaker of the Chilean parliament strikes his gavel, an explosion destroys the D'Anconia docks. The Chileans later find that they have nationalized a pile of junk, because Francisco d'Anconia blew everything up on the last second that he actually owned it. To boast of his act, Francisco alters the message on the scrolling calendar display in New York City, to read:

| “ | Brother, you asked for it! | ” |

Throughout September and October, three crippling disasters strike the country, usually in areas that Dagny has just managed to save rail service to. Then at last the Terminal shuts down when the signal interlocking system fails. Dagny organizes a lantern brigade to move trains in and out. Then, to her shock, she discovers John Galt among the unskilled labor force. After she finishes giving her orders, she rushes to an abandoned tunnel. Galt follows, and the two of them finally come together. Galt reveals that he has spied on her for ten years, that he went to work for Taggart Transcontinental as a track walker after he quit the Twentieth Century Motor Company, that he knows that he has now placed his life in jeopardy by letting Dagny know that he is that close to her, and that when the time comes for her to quit, she should draw a dollar sign in chalk on the plinth of the statue of Nathaniel Taggart that stands in the Terminal concourse, and he will come for her at her apartment. She is not, of course, prepared to do this. Yet.

In November, the government attempts to persuade Rearden to sign on to the Steel Unification Plan, similar to the Railroad Unification Plan. Rearden refuses and returns to his mills. There he finds a riot in progress. The "Wet Nurse," shot in the back and dying, tells him that the riot is staged and is being carried out by infiltrators who were never really Rearden's employees. Rearden's regular workers, led by the recently hired furnace foreman, beat back the rioters and stop some of them from killing Rearden. The furnace foreman is in fact Francisco d'Anconia, who now persuades Rearden to quit business. When he quits, several other regulars quit with him.

Dagny is then asked to participate in another radio and television program in which President Thompson will deliver "a report on the world crisis." But when the appointed hour falls, the government engineers have lost control of the airwaves and are off the air.

Then a voice begins to speak:

| “ | Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Thompson will not speak to you tonight. His time is up. I have taken it over. You were to hear a report on the world crisis. That is exactly what you are going to hear. | ” |

Three people recognize the voice at once: Dagny, Dr. Robert Stadler, and Dagny's assistant, Edward "Eddie" Willers. The voice in fact belongs to John Galt, and identifies itself as such. But Robert Stadler remembers John Galt as one of three students who once majored both in physics and philosophy at his old university—and the other two were Francisco d'Anconia and Ragnar Danneskjold. Eddie Willers remembers the voice as belonging to an anonymous track walker whom he used to tell his troubles to over lunch in the Terminal. What becomes clear now is that John Galt was spying on Dagny Taggart for ten years, and sometimes when Eddie Willers would foolishly drop a name to Galt (whom he never identified until this occasion), the owner of that name would "vanish."

For three hours, John Galt expounds on his actions: that he and the vanished ones are "on strike" and will settle for nothing less than a system in which the government never interferes with anyone.

Dagny then does a foolish thing: she tracks down John Galt to his apartment in New York. The federal authorities have her watched, and thus are able to arrest John Galt. For about a week they attempt to persuade John Galt to become the "Economic Dictator" of the country, but he refuses, after demonstrating that no person in any such position could possibly make the broken-down system work. Nevertheless the authorities insist on announcing the "John Galt Plan for renewed prosperity" and even try to have Galt address the nation—at the point of a gun. In reply, Galt waits until the last second, and then says,

| “ | Get...out of my way. | ” |

Robert Stadler has known all along that Galt would never cooperate, so he rushes to the site of Project X, intending to seize control of it for himself. But another government operative named Cuffy Meigs has beaten him to it. The two men then struggle over the controls of the so-called Xylophone, and when Meigs pulls one lever too many, the weapon destroys the complex and everything within a hundred miles, including the one remaining railroad bridge across the Mississippi River.

Dagny watches as Galt is led away, and is now determined to quit the world herself, before anyone suspects her true feelings for Galt. She packs very light, and receives with indifference the report that the Taggart Bridge has been destroyed by sound rays from Project X and that the two halves of the country are now cut off. She leaves her headquarters for the last time— chalking a dollar sign on Nat Taggart's plinth as she leaves, just "because it's there"—and meets Francisco d'Anconia, to whom she finally swears the oath that John Galt wrote twelve years before:

| “ | I swear, by my life and my love of it, that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine. | ” |

In the final scenes, Floyd Ferris, Wesley Mouch (Coordinator of Economic Planning and Natural Resources), and James Taggart take Galt to the secret laboratory of the State Science Institute and try to torture Galt into cooperating. When the torture machine malfunctions and only John Galt knows how to repair it, the technician flees the scene, Wesley Mouch loses his nerve, and James Taggart goes insane with the realization that all he has ever wanted to do was to make better men than he suffer. Shortly afterward, Dagny, Francisco, Hank Rearden, and Ragnar all descend on the secret laboratory, kill some of its guards, and rescue Galt. As the rescue plane heads west, the entire eastern seaboard is plunged into darkness.

Eddie Willers, who has traveled westward to negotiate a settlement with a radical faction who has seized power in California and imposed a "departure tax" on trains, is aboard the Comet when it breaks down for the last time. No one is able to start the train again, and Eddie finds himself left alone with the abandoned train as a wagon train takes all the passengers and crew off.

Eventually, the people of Mulligan's Valley realize that the American economy, the last of the world's economies, has collapsed totally and that the federal government essentially has nothing to govern anymore. John Galt declares that "the road is clear" and that his people will emerge from their valley and rebuild the economy on their own terms.

Spoilers end here.

Themes

The role of the mind

"The role of the mind in man's existence" was, by her own account, Rand's primary theme in this novel. Man cannot exist qua man if he does not think. Furthermore, human thought, applied to practical concerns, makes possible every improvement in human lifestyle since the beginning of civilization. Wealth is the product of thought, and is produced, not gathered like fruit or grass. Therefore, if all the most creative and talented people were to "go on strike," the economy that those talents made possible would collapse.

History provides ample precedent for the collapse of human civilization whenever the mind cannot function or communicate for one reason or another. The fall of the Roman Empire caused a collapse of law and order, with the result that the remarkable technology that the Romans had either developed or successfully copied from the Greeks was lost. Serious students of ancient and medieval history are often surprised to learn that the Romans had running water, indoor plumbing, central heating, and metalled roads; all these things fell into disrepair, and the technology for these things was forgotten and required near-complete reinvention.

Until recently, no one has threatened to call such a "strike of the men of the mind" as John Galt calls. But socialist societies, or democratic republics who flirt with socialist ideas, have all suffered from varying rates of defection, or "brain drainage," in which talented people move elsewhere, seeking a society that will appreciate their talents without burdening them with disproportionate taxes and regulations. The growth of the Tax Day Tea Party movement has included calls for just such a strike, in which the men of the mind do not defect, but neither do they work as hard as they otherwise would.

Workability of the strike

The price for John Galt's strike is high. John Galt provides no "strike fund," and the only such fund is the savings that any given striker might have. Furthermore, the collapse of the economy, and even of civilization, affects striker and "scab" alike—at least until Ellis Wyatt leads a large cadre of entrepreneurs and developers to Midas Mulligan's secluded valley and applies his particular talents to transform a rural refuge into a highly developed industrial-commercial community. (Arguably, Ragnar Danneskjold's privateering activities provide the equivalent of a "strike fund," but the strikers do not use those funds for the usual purpose of "tiding over" until settlement is possible.) And even the enhanced development of this community sees creative people taking jobs that are far below what their talents or work ethic would normally allow them to apply for.

This, however, illustrates another point that Rand made, whether she intended to make it or not: that even if mind and labor "need" one another, labor needs mind far more than does mind need labor. A talented man can function as a laborer if he must, but a laborer can never function in a job above his talents.

Labor and capital

Note that the tension in the novel is never between labor and capital, but between labor and mind, or rather labor and talent. Capital alone, if not properly directed, will simply be wasted. The best illustration of this is the failure of the Community National Bank of Rome, Wisconsin, after Lee Hunsacker buys the bankrupt Twentieth Century Motor Company and then finds himself unable to make it run. Therefore, capital, in Rand's system, must remain in the hands of the talented. The best way to assure that outcome is simply not to tax capital. In that manner, even if capital is mis-spent, talented individuals will inevitably accumulate more of it and use it wisely.

The Mind-Body Dichotomy

Rand, as mentioned above, sought to criticize the mind-body dichotomy. This is any attempt to divorce the mind from everyday human needs (genuine needs, not "need" in the Marxian sense). Rand found two forms of this dichotomy worthy of reproach:

Mind and Romance

Rand believed that the mind is far more important than most people appreciate in dictating one's romantic choices. As Francisco d'Anconia says on one occasion:

| “ | Tell me what a man finds sexually attractive and I will tell you his entire philosophy of life. Show me the woman he [is involved] with and I will tell you his opinion of himself. | ” |

Henry Rearden makes two key mistakes in this regard, and both of them cost him dearly before his final transformation is complete. First, he marries Lillian Rearden, who, though described as physically beautiful, has nothing but scorn for his talents as a businessman and as an inventor, and also moves in a circle of friends who are dedicated to the destruction of talented men like Rearden. Second, though he has an affair with Dagny Taggart, he does not fully realize that his feelings for her are natural (flowing from his own nature) and even honorable. If he had not regarded the sexual impulse as inherently dishonorable, he probably would never have married anyone like Lillian.

Pure and Applied Science

If Henry Rearden makes one kind of mistake by splitting mind from body, Robert Stadler makes another. He believes that the best minds should stand above the "mundane" concerns that are the province of engineers. Thus when Dagny Taggart describes to him the prototype of an electrostatic motor, Stadler wonders aloud why the mind that could create such a motor is not involved in "pure" research.

The very terminology of "pure" and "applied" science illustrates this form of the mind-body dichotomy in real life. The full name of almost any school or department of engineering is "school (or department) of engineering and applied science." And in fact, practical inventions rarely receive the highest honor that organized science can bestow, the Nobel Prize, unless they have a medical application. Thus perhaps organized science discards the mind-body dichotomy when an invention might help save a life. For example, the award of the Nobel Prize in Biology to Solomon Bernson and Rosalind Yalow for their development of radioimmunoassay techniques was a rare event. Furthermore, such a practical invention in a field other than medicine will wait for years before it finds practical application. The laser, for example, was first built in 1960 but did not find an out-of-the-laboratory application until 1965, when the Western Electric company first used lasers to pierce industrial diamonds.

In sharp contrast, John Galt does breakthrough-quality work in the understanding of static electricity and then constructs a working device that will find immediate application. Furthermore, his laboratory is not in a university, nor in a government institution, but in a privately owned automobile engine factory.

Robert Stadler's experience is even worse than a missed opportunity. Like John Galt, Robert Stadler does breakthrough-quality work, this time in the field of sonic physics. But Stadler's work finds application, not in a practical device that will enhance human comfort, but in a weapon of mass destruction, to wit, Project X.

Brotherly Love

"Brotherly love," as socialists understand and apply the term, is a fallacious concept in the Randian system. The concept arises from a misunderstanding of Cain's misguided protest against God after the murder of Abel:Am I my brother's keeper? Genesis 4:9 (NASB)

God asks Cain that question because He is investigating a murder. But the socialists misapply that verse, and the teachings of Jesus Christ concerning voluntary charity, to suggest that any man is his brother's keeper, and that a "brother's" needs come before his own. This begs the question of which brother's needs come first, and requires an overarching authority to decide the issue. This last was a thing that Rand did not recognize that any government had a right to decide for any of its citizens or subjects.

Most of the novel's scenes demonstrate the practical effects of this policy, all of which are negative. But Rand also lodges her philosophical and moral objection. She does this in several places, most notably the defiant speech by Henry Rearden before a special administrative court, the many statements by Francisco d'Anconia in his conversations with Rearden and his commentaries to others, and the three-hour speech made by John Galt in which he finally tells everyone who can hear his voice to go on strike. As Henry Rearden says, "It is not your particular policy that I challenge, but your moral premise."

Original Sin

Rand rejected totally the concept of original sin. Correctly or incorrectly, she blamed that concept for the power and primacy of socialist ideals. Man, she claimed, was basically good, and ought to be permitted to be all that he could be. Yet she probably would not have approved of certain despotic historical figures who wanted to be all that they could be. Julius Caesar is probably the prize example.

Hypocrisy

One concept that Rand demonstrates more in direct narration than in exposition is the high prevalence of hypocrisy in the behavior of the villains. For example, Gerald Starnes, Jr., the Director of Production of the Twentieth Century Motor Company, appropriates vast amounts of money for himself through schemes that one might describe as "creative financing." While so doing, he insists that his ostentatious show of wealth is necessary for making a good showing for the company that he heads. His workers recognize this hypocrisy and hate him for it. As shop foreman Jeff Allen says,

| “ | Any cheap show-off who's got nothing to parade but his cash, is bad enough—except that he makes no bones about the cash being his, and you're free to gape at him or not, as you wish, and mostly you don't. But when a [blackguard] puts on an act and keeps spouting that he doesn't care for material wealth, that he's only serving 'the family,' that all the lushness is not for himself, but for our sake and for the common good, because it's necessary to keep up the prestige of the company and of the noble plan in the eyes of the public—then that's when you learn to hate the creature as you've never hated anything human. | ” |

James Taggart is another prize example of hypocrisy, as is Lillian Rearden.

But Rand never says whether hypocrisy or a brazen willingness actually to live up to socialist ideas is the worse sin. Gerald's sister Ivy, for example, deliberately avoids any ostentatious show of wealth, and in fact takes very little compensation for herself. But in fact she savors the exercise of raw power over other people's lives. She also displays her poverty as a testimony against anyone who, for whatever reason, has more wealth than she has. This, then, becomes another form of hypocrisy, because Ivy, though she never robs anyone physically, still robs them spiritually. Again to quote the witness character Jeff Allen,

| “ | [P]rofit...depends on what you're after, and what [some socialist politicians and leaders are] after, not all the money in the universe [can] buy. Money is too clean and innocent for that. | ” |

Historical parallels

- When Richard Nixon began his "four-phase program" of economic controls, beginning with his ninety-day wage-and-price freeze, Miss Rand commented tartly that she had anticipated that very sort of program in her work.

- Miss Rand chose November 22 for the date of the "report on the world crisis." On that very date, six years after the publication of the novel, Lee Harvey Oswald shot and killed John F. Kennedy.

- When the Northeast Blackout of 1965 occurred, many students of Objectivism remembered tuning in their radios and half expecting someone to say, "This is John Galt speaking...."

Time setting

- Main Article: Atlas Shrugged (chronology)

The novel does not state when it is set in time. That is, it gives no years. An earlier (since abandoned) plan for the film adaptation (see below) called for setting it during the middle of the 1920s.[3]

The motion picture Atlas Shrugged, Part 1 posits an index date of September 2, 2016.

Criticism

- Main Article: Atlas Shrugged (criticism)

Atlas Shrugged has never been a critical favorite. Indeed, Barbara Branden, as quoted by Harold Leiendecker,[4] summed up the criticism thus:

| “ | The reviews of We the Living had been bad. The reviews of The Fountainhead had been worse. The reviews of Atlas Shrugged were savage. | ” |

Not all the reviews were savage, but most of them were. Even some conservative reviewers spoke scathingly of it. The most infamous of these reviews came from Whittaker Chambers, who said of the novel in National Review that every page screams, "To a gas chamber—go!"[5] Nathaniel Branden said of it, among other things, that it taught emotional repression as a virtue.[6]

Leiendecker, however, reminds us that many of the nefarious laws and "directives" that the novel mentions have in fact come to pass. His chief criticism was that the dialog (and in John Galt's memorable case, monolog) of the heroes and anti-villains of the work often sounds "stilted," while the words of the villains ring true to their respective real-life anti-types.[4]

As might be expected, the Roman Catholic Church and its various organs found fault with the explicit atheism of the novel, and especially John Galt's specific rejection of the notion of original sin, and Francisco d'Anconia's statement that a rational man does not "render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's," because "he permits no Caesars."[1]

Recently, the Ayn Rand Center has issued a new review of the novel, and an analysis of the parallels between the fictitious Mr. Thompson administration and the real-life Barack Hussein Obama administration (and is unsparing of the United States Congress as well).[7]

Science Fiction elements

At least four inventions in this novel have never yet been duplicated and would therefore qualify as elements of science fiction. They are:

- John Galt's electrostatic motor,

- Rearden Metal,

- Project X, and

- the refractor-ray screen that protects Galt's Gulch from detection from the air above it.

The film adaptation (see below) replaces the electrostatic motor with a quantum motor, that uses electrostatic effects that typically operate in a quantum vacuum.

Film Adaptation

- Main Article: Atlas Shrugged, Part 1

Almost since the initial publication of the novel, the most avid followers of Ayn Rand, who called themselves "students of Objectivism," have wished to see the novel adapted as a motion picture. The first of Ayn Rand's novels to be adapted for film was The Fountainhead. Ayn Rand herself wrote the screenplay for that film, in which Gary Cooper portrayed the leading protagonist, Howard Roark.

The major difficulties with adapting Atlas Shrugged to film were twofold. One, the story was simply too long for any one film to do it justice. Two, Hollywood values were already beginning to diverge from American values, and the prospect of a film that would be remotely faithful, either to the novel or to Ayn Rand's original motivation for writing it, always seemed rather remote.

Yet different producers have attempted a film adaptation for a long time. At one point, according to the trade paper Variety, Alfred S. Ruddy attempted for several years to do his own adaptation. Among the names of actors and actresses that were mentioned in connection with Ruddy's efforts were those of Clint Eastwood, Robert Redford, and Faye Dunaway.[3]

The Baldwin Entertainment company recently tried to produce an adaptation, but gave it up. Then a brand-new company, calling itself The Strike Productions, took the project over[3], with the intent to make three films, one for each of the three parts of the novel. They hired their own writer and director, and more to the point, the cast of the film consist entirely of actors and actresses who have appeared, if at all, in projects with which very few, outside of dedicated movie "buffs," are likely to be familiar.

Atlas Shrugged, Part 1 moves the action forward to 2016. Obviously it updates many forms of communications and media. But it does not update all the situations—for example, it does not tell the story of a Taggart Intercontinental Airline. Instead it projects a future in which:

- The Middle East has totally imploded, and all importation of oil to the United States stops.

- Motor fuel cannot be had at a price less than $37.50 per gallon—in the United States.

- The United States Navy has lost all its strength, and thus cannot cope with a lone privateer (Ragnar Danneskjold) hijacking government relief cargoes.

- Railroads are the primary mode of transport for passengers and freight. Commercial aviation is dead. A quick opening scene shows the demolition of a Boeing 727 (or perhaps an MD-80).

- Instead of a National Rail Passenger Corporation (Amtrak), the Taggart Transcontinental Railroad has existed and operated continuously for more than a century. This is the only concession to alternate history that this film makes.

Atlas Shrugged, Part 1 premiered on April 15, 2011. Its reception was definitely negative from mainstream reviewers, like the novel before it. From students of Objectivism it received mixed reviews.

On November 8, 2011, The Strike Productions, now renamed Atlas Productions, released the film for home viewing on the DVD and Blu-ray formats. Before this release, several political events occurred that bore a striking resemblance to events to which the film alluded. They were:

- Occupy Wall Street

- The campaign by the National Labor Relations Board to forbid the Boeing Aerospace Corporation to build an aircraft plant in South Carolina, a right to work State.

Recent popular mention

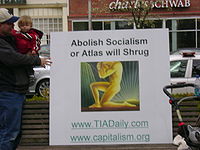

In the context of the massive taxation and spending policies proposed by President Barack Obama and the United States Congress, Atlas Shrugged has enjoyed a resurgence in popularity.[8] Activists have mentioned the name of the novel, and of its primary anti-villain, in commentaries and on placards.

Many liberal commentators in fact have asked scathingly whether certain persons allegedly threatening to "go Galt" mean what they say, and from the tone of their remarks, they seem quite willing to bid such people "good riddance." That willingness might soon be put to the test. A group calling itself "Tea Party Nation" called a general strike of conservative individuals on July 30, 2009, in obvious imitation of John Galt's call to "stop supporting [one's] own destroyers."[9][10] More recently, Investors' Business Daily has found that forty-five percent of doctors surveyed state that they would consider quitting their profession if the Obama Administration's proposed socialization of medicine becomes law.[11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "History of Atlas Shrugged," The Ayn Rand Institute, n.d. Accessed May 5, 2009. <http://atlasshrugged.com/the-book/genesis-of-the-book/>

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Branden B, The Passion of Ayn Rand, ca. 1985

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Entry for Atlas Shrugged," Internet Movie Database, accessed April 21, 2009. <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0480239/>

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Leiendecker H, "Atlas Shrugged," ASPEC Writers' Workshop, n.d. Accessed May 5, 2009. <http://www.eckerd.edu/aspec/writers/atlas_shrugged.htm>

- ↑ Chambers W, "Big Sister Is Watching You," National Review, December 28, 1957. Hosted at National Review Online, published January 5, 2005. Accessed May 1, 2009. <http://www.nationalreview.com/flashback/flashback200501050715.asp>

- ↑ Branden N, "The Benefits and Hazards of the Philosophy of Ayn Rand," audio presentation, 1984. Transcript hosted at <http://www.nathanielbranden.com/catalog/articles_essays/benefits_and_hazards.html>.

- ↑ Brook Y, Atlas Shrugged's Timeless Moral: Profit-Making is Virtue, not Vice," Investors Business Daily, 20 July 2010.

- ↑ "Ayn Rand: Capitalism’s enduring crusader," The Week, April 24, 2009. <http://www.theweek.com/article/index/95431/Ayn_Rand_Capitalisms_enduring_crusader>

- ↑ Tea Party Nation official site.

- ↑ Martin AG, "Conservatives to 'Go Galt' on July 30; Protest Intensifies," Columbia Conservative Examiner, June 30, 2009. <http://www.examiner.com/x-3704-Columbia-Conservative-Examiner~y2009m6d30-Conservatives-to-go-Galt-on-July-30-protest-infensifies>

- ↑ Jones T, "45% Of Doctors Would Consider Quitting If Congress Passes Health Care Overhaul," Investors' Business Daily, 16 September 2009. Quoted in "Doctors Threaten to Go Galt if ObamaCare Passes,", Stop the ACLU, 16 September 2009.

External links

- Atlas Shrugged Official site designed and published by The Ayn Rand Institute

- Atlas Shrugged Student's notes by SparkNotes.

- Atlas Shrugged Movie News Clearinghouse of fact and rumor concerning a planned motion-picture adaptation of the novel.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||