Difference between revisions of "Economics Lecture Eleven"

(→Assignment: done) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Economics_Lectures}} | {{Economics_Lectures}} | ||

| − | + | On the CLEP exam, slightly less than 10% of the questions are about graphs. To answer them correctly, it helps not to be overwhelmed or give up too quickly. The questions simply test and retest a few basic principles in economics. A favorite topic of graphical questions concerns where a monopolist sets his price. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Econ13c.jpg|right|250px|thumb|Figure C]] | |

| − | + | A monopolist has no supply curve, because he is the only supplier. There is only a demand curve, a marginal revenue curve, and some cost curves for a monopolist. If given a graph with these curves, simply find where the marginal revenue curve intersects the marginal cost curve, and that '''''determines the quantity sold'''''. | |

| − | = | + | On the graph to the right (Figure C), there is no supply curve so you know that this represents a monopolist. A typical question is to ask you where the monopolist sets his price in order to maximize his profits. To find this price point, recall that a monopolist sets his price where MC=MR. The graph gives you curves for both MC and MR, so find where they intersect: point A. But that point gives you the quantity supplied, not the price demanded. To find the demand price at the quantity supplied, you have to find the corresponding price point on the demand curve. You trace a line vertically from point A to find the price on the demand curve: point D in Figure C. |

| − | + | That is the answer to a question about where a monopolist sets his price, but that is not the best price for the public. It is higher than the price the public would enjoy if the market were fully competitive. Another question on a CLEP exam might ask where the competitive price would be, also known as the "allocatively efficient" price because it represents the most efficient allocation of resources. That price (and quantity) is where the MC curve intersects the demand curve: point B in Figure C. | |

| − | + | Figure C also has a curve for average total cost (ATC). Recall that a firm shuts down in the long run when ATC>P; and the firm shuts down in the short run when AVC>P, but keeps operating in the short run when AVC<P<ATC. This is because "variable cost" is a short run issue, while "total cost" is a long run issue. Does the firm in Figure C shut down? No, because we determined above that the monopolist can sell at point D, and there ATC=P. He is covering (paying for) all his costs. The firm can continue in business. | |

| − | + | Here are some other common graphical questions: | |

| − | *the | + | *'''''optimal''''' market price: where the supply curve intersects the demand curve. A monopolist has no supply curve and it sells at MC=MR, which has a price higher than the optimal price of MC=P. |

| − | + | *consumer surplus (the benefit to the consumer where the demand curve is higher than price paid, because the consumers pay less than they were willing to pay, as when you would have paid $15 to see a movie but the charge was only $10: your consumer surplus is $5) | |

| − | * | + | *deadweight loss: the lost consumer surplus explained above AND (in the case of a tax) the lost producer surplus (benefit to the seller who was willing to produce at a price less than what he sold it for) |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | * | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | See the graph near the end of Lecture 7 for an explanation of both the consumer and producer surplus, which are also useful in determining the graphical region for the deadweight loss. | |

| − | + | == Government Policy == | |

| − | + | As mentioned in a prior Lecture, 10% of the CLEP exam is on government policy. In addition what we have already learned, we need to know: | |

| − | + | * market distribution of income (Lorenz curve) | |

| + | * market failure and imbalances in information | ||

| − | + | The Lorenz curve (also known as the Lorenz diagram) is a graph displaying a comparison of the actual distribution of income in a society against a hypothetical '''''equal''''' distribution of income. This could be done by plotting the percent of overall income on the y-axis and the percent of families on the x-axis. A hypothetical (imaginary) '''''equal''''' distribution of income would be a straight line at 45 degrees (the line y=x). But the actual distribution of income would not rise as quickly as that straight line. Going from the poorest 0% to perhaps 20% (on the x-axis) of families would have almost no increase in cumulative income (on the y-axis), and beyond that the slope of the curve for actual income would gradually increase until the richest earners near the top 100% of families were included. | |

| − | + | On the CLEP exam, a question about the Lorenz curve will likely seek an answer that government should try to equalize the income distribution in society. | |

| − | + | Not everyone agrees. Churches once played a bigger role in "sharing the wealth," and they did it better than government does. Do we want government to replace churches? Of course not. | |

| − | + | But government may have a proper role in correcting for imbalances in information, in order to make sure that people have a better understanding of what they are buying. Food products are required by government to disclose their contents, and how much fat they contain. Cigarette companies are required to say that their product causes cancer and hurts people. In some states abortionists are required to disclose some of the harm that abortion causes. Government regulations that improve the knowledge of the public may be beneficial, and may even help reduce negative externalities. | |

| − | + | Sometimes markets fail to work entirely, as when competition disappears and there is only one supplier. Imagine the only gas station in town after a hurricane wipes out all his competitors. Or when the biggest banks fail, all at once. The "bail out" before the 2008 elections was an example of government trying to prevent a total market failure. Many disagree with government interference in cases of "market failure," however. What's your view? | |

| − | + | == Production Possibilities == | |

| − | + | Nearly 5% of CLEP exam is devoted to questions about "production possibilities." These are easy questions to answer. | |

| − | ( | + | "Production possibilities," or "Possibilities of production," mean all the different combinations of goods a nation can produce. The United States can produce X cars and Y trucks, for example. Or it could produce more than X cars and fewer than Y trucks. We could graph the number of cars on the Y-axis and the number of trucks on the X-axis, and draw a “production possibility” curve through all the possible combinations. It would be downward sloping: more trucks mean fewer cars, and vice-versa. The opportunity cost of producing more cars is the loss in production of trucks. In the production possibility curve for cars and boats shown in Figure A (below), the opportunity cost of moving from point A to point B is 100 cars. |

| − | ( | + | The shape of the production possibilities curve (often called the "production possibilities frontier") is dictated by the high opportunity cost of trying to convert an entire nation's factories from making one type of good to making another type. Imagine having a car factory and a truck factory, and then trying to convert the entire truck factory such that it makes only cars. At a fixed level of expense, the truck factory is not going to be able to make as many cars as the trucks it was designed to make. So converting the nation from, for example, a level of 500 cars and 500 trucks to as many cars as possible will probably not be able to reach a level of 1000 cars and zero trucks. Instead, it will probably top off at a number less than 1000, and hence the tapering of the production possibilities curve near the two axes. |

| − | + | If the overall number of workers or investment capital increased, then you could produce more of everything. The entire production possibilities graph (or “production possibilities frontier”) would shift upward and to the right. An improvement in technology would have the same effect. An increase in bureaucracy or administrative costs, however, would have the opposite effect, forcing a contraction in overall production. | |

| − | + | There are several assumptions made in constructing a production possibilities frontier. These assumptions are more realistic in the short run than in the long run: | |

| − | + | *there are only two goods, and production is a trade-off between the goods: making more of one means making less of the other. | |

| − | + | *there is no increase in waste or regulation; if there is new waste or costly regulation, then the point of production moves to somewhere inside the curve rather than on it. | |

| − | + | *the same fixed resources are used for making the same two goods, and technology does not improve | |

| + | *there is "full employment," such that adding workers requires taking them away from another task | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Econ13ab.jpg|right|250px|thumb|Figures A and B]] | |

| − | + | If there are inefficiencies in a nation's economy, then its production will be inside the production possibilities curve. Due to the inefficiencies, the nation will not be producing as much as it could if it were efficient. Just as an increase in capital or an improvement in technology can cause an increase in the production of all goods, an increase in a nation's efficiency can cause its production to increase for all goods, from a point inside the production possibilities curve to a point on the curve. | |

| − | ( | + | Sometimes in politics the trade-off between producing goods is described as “guns versus butter.” The more guns (e.g., military weapons) we make, the less butter (e.g., food and domestic services) we can produce. The idea is that there is a trade-off between spending money on our military and spending it on domestic goods and services. |

| − | + | On a personal level, it is usually impossible to do two things at once. Either you spend the next hour working on this course, or you spend it doing something else. You could graph a production possibility curve for how you spend 24 hours each day. It could be 8 hours sleeping, 1 hour exercising, 1 hour traveling to destinations, 3 hours cooking and eating, 6 hours studying, 1 hour relaxing, and 4 hours working at a job. If you take an hour away from one activity, then you can add it to another. Your production possibility curve would represent all the possibilities. | |

| − | + | == Review: Cost Measures== | |

| − | + | Consider Figure B to the above right. In order to master economics, develop a habit of asking yourself what you would do if you were the owner of a firm with these costs. Ask yourself: if your output is selling at a price of P<sub>1</sub>, are you making a profit?<ref>No.</ref> Should you stay in business?<ref>No, because the price is less than both AVC and ATC.</ref> | |

| − | + | Next consider if your output is selling at a price of P<sub>2</sub>. Are you making a profit there?<ref>You are making a daily profit because P>AVC, but losing money when all your fixed costs are included because P<ATC.</ref> Should you stay in business?<ref>Yes, because P>AVC so you are making a marginal profit, but not covering all your original costs.</ref> | |

| − | + | Finally consider what to do if your output is selling at a price P<sub>3</sub>. Are you making a profit at that price point?<ref>Yes.</ref> Should you stay in business?<ref>Yes, absolutely. Your price is greater than both your ATC and AVC. You're making good money at this price point for your output. (But note that output is not at Q<sub>3</sub> in the graph, but is where MC=P<sub>3</sub>.)</ref> | |

| − | + | == The Law of Comparative Advantage == | |

| − | + | There is an interesting concept in economics known as the Law of Comparative Advantage. The CLEP exam usually asks two questions about it. | |

| − | + | '''''The Law of Comparative Advantage states that if one nation can produce two goods more efficiently than another nation, then the first nation should devote all its resources to producing the good that it makes more efficiently, and let the other nation produce the second good, and then trade one for the other.''''' This Law can apply to individuals and firms as well as countries. | |

| − | + | Note that this is not what you might first expect. You might expect the first nation to produce BOTH goods, since it can produce both goods more efficiently than the other nation. But upon closer examination it becomes clear that by focusing on what it does best, and produces more efficiently, the first nation can produce more and then trade for the rest, and be better off. Put another way, "do what you do best!" | |

| − | + | In sports, sometimes an athlete is good at one sport (e.g., baseball) but great at another sport (e.g., football). John Elway and Deion Sanders, for example were great at football but only good at baseball. John Elway did what he did best: he played only professional football, and became one of the greatest quarterbacks ever. Deion Sanders played both football and baseball, and perhaps did not achieve as much at either as he could have by focusing what he did best. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Economists observe that utilizing the Law of Comparative Advantage can improve the production possibilities. Suppose your job paid you $9 but you could hire a cook for $6. Then it might make sense for you to work one more hour and hire someone to save you one hour of cooking. In the absence of taxes, you would be $3 better off. Then you could work one-third of an hour less to make the same money (after expenses) as before. That extra one-third of an hour could be added to your sports or relaxation time. You have moved your “production possibilities frontier” (the curve of all possibilities) outward, for greater benefit. | |

| − | + | === Example === | |

| − | + | Suppose this is how much in resources it costs the Yankees and Mets to produce great pitchers or outfielders: | |

| − | + | <div style=float:left; padding: 20px"> | |

| + | {|style="border-collapse:collapse" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; padding:10px"|Yankees | ||

| + | |style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; padding:10px"|Mets | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !rowspan=2 style="padding:10px"| | ||

| + | |style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; padding:10px"|outfielders | ||

| + | |style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; padding:10px"|10 resource units | ||

| + | |style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; padding:10px"|5 resource units | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; padding:10px"|pitchers | ||

| + | |style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; padding:10px"|9 resource units | ||

| + | |style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; padding:10px"|3 resource units | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | + | Even though the Mets can produce outfielders more efficiently than the Yankees can, the Mets are better off spending all their resources developing pitchers and then trading with the Yankees to obtain outfielders. | |

| − | + | [[David Ricardo]] (1772-1823), one of the greatest classical (conservative) economists, first developed the Law of Comparative Advantage. Note that "comparative advantage" is not the same as "competitive advantage," which simply means something that gives you an advantage in competition over someone else, such as a better location for your gas station. | |

| − | + | ==Review: Inputs== | |

| − | + | Often we have focused on the OUTPUT of a firm. How many goods will it sell at what price? The price elasticity of its demand, for example, looks at how demand for its output changes based on a change in its price. | |

| − | + | Marketing and sales also focus on the output of a company. Marketing consists of advertising and promoting the goods. Sales, the most important aspect of almost any company, consist of persuading customers to buy the company’s good or service. The most valued employees of almost any company are its top salesmen and saleswomen. They are the ones that bring in the money to the company. | |

| − | + | If we were to hold a dinner with a speaker, the output would consist of the seats at the dinner and the sales effort consists of selling the spots and receiving money in return. In a homeschool course, the output is the lectures and the sales effort consists of selling places in the course. Colleges, in turn, compete for students who can pay their tuition and fees. Many colleges struggle because they have a difficult time attracting enough students to pay tuition. In fact, very few new colleges have started in the past twenty years, and the new ones have been more conservative than the older ones. | |

| − | + | There is another side to every company: its own inputs and the costs they incur. For a bus trip to D.C., the inputs are the cost of the buses and perhaps some food costs. Lowering the costs of those inputs makes the project more affordable. | |

| − | + | This is like offense and defense in sports. The people on offense are the salesmen, trying to score points. The people on defense are the buyers of inputs for the company, trying to keep the expenses down. They are opposite jobs, often requiring opposite personalities. Extravagant people make for better salesmen; frugal people are often better buyers of inputs for a company. | |

| − | + | Experienced businessmen will emphasize that profits are made by keeping expenses down. After all, profits are the main goal of a typical business. If a company is buying food from supplier number one and can reduce costs by going to supplier number two, then the rational action is to change suppliers from number one to number two. | |

| − | + | Keeping costs down was what made Wal-Mart so powerful. Its marketing and advertising have only been mediocre. But it is the best in reducing costs. It pays its employees relatively little; it opposes unions forming among its workers; and it is ruthless in bargaining down the costs of its suppliers. Wal-Mart has made immense profits as a result. | |

| − | + | Does that seem unfair? No one has to supply Wal-Mart goods at a low price. If a supplier does not want to do business with Wal-Mart, then it doesn’t have to. No one has to take a job there either! | |

| − | + | In general, the demand for inputs by firms is called the “derived demand for inputs,” because it is derived from the consumer demand for the products the company sells. Because your family wants to buy gas from a gas station, this demand creates a demand by the gas station for its inputs: the gas and labor. | |

| − | + | ==Review: Monopsony== | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | '''''A monopsony means only one buyer'''''. It occurs when one buyer holds a monopoly on all purchases. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The best example of a monopsony is when there is only one employer (only one "buyer" of labor) in a small, isolated town. If you want a job in that town, then your only place to work is at that company. Of course, very few towns are actually limited to just one employer. But for a certain type of job, there may be only one employer, and it has a monopsony over that type of job. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | A monopsony is different from a competitively hiring firm in one significant way. When a monopsony needs to hire an additional worker, then it has to raise the wages for all its workers to that higher wage level in order to hire an additional worker. Its marginal cost for paying for this "factor" (labor), also known as its marginal factor cost (“MFC”), is more than the wage of merely the one additional worker. MFC equals the W of the additional worker PLUS the increased wage of all the other workers. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | For example, if a monopsony can hire 10 workers at $6 or 11 workers at $7, then its MFC of hiring an 11th worker is $7 + (10 x ($7-$6)) = $17. | |

| − | = | + | For a competitive firm, in contrast, MFC=W because it can hire all the workers it needs at the market wage, without causing the market wage to rise for all its workers. |

| − | + | This example helps us understand why the marginal revenue (MR) for a monopoly (one seller) when it increases its price is not the same as the price P of the additional good that it sells. When a monopoly raises its price to obtain more revenue (and more profits), it raises its price on ALL its goods. MR for that increase in price is not simply P, but it is the increased price on all its goods times the quantity of those goods. A monopoly sells where MC=MR, but that is not the same place as where MC=P, because MR does not equal P for a monopoly. MR does equal P for a perfectly competitive firm. | |

| − | + | ===Honors: Example=== | |

| − | + | Let’s start with this simple equation: Profits = Total revenue - Total cost. That’s easy enough. Now let’s break it down, where P=Price, Q=Quantity, W=Wage, and L=Labor units: | |

| − | + | :Profits = (P x Q) - (W x L) - other non-labor input costs | |

| + | Now suppose we add one more worker to our company. We will have to pay him a wage of W, so the marginal factor cost of one more worker is W (assuming a competitive market). What is his marginal benefit to our company? It is P x MP. | ||

| − | + | When does a company hire that additional worker? When the change in profit is greater than zero. That occurs when (P x MP) > W. | |

| + | |||

| + | Example: suppose a firm has a declining marginal product for each additional laborer hired, such that: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !Labor Units (L) | ||

| + | !Marginal Product (MP) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |1 | ||

| + | |20 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |2 | ||

| + | |18 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |3 | ||

| + | |16 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |4 | ||

| + | |14 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |5 | ||

| + | |12 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |6 | ||

| + | |10 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |7 | ||

| + | |8 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Suppose the wage W for each employee is $70 and the price the output is sold for is $5. How many workers should you hire? | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you hired just one employee, then you would make 20 x $5 = $100 in revenue. But your cost was only W=$70, so you made a profit of $30! You’ll hire at least one employee. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you hire a second employee, then you would make (20+18) x $5 = $190. But your cost was only $70 x 2 = $140, so your profit is $50! You’re doing even better, so you hire the second employee. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Skip down to hiring employee number 6. Then you make (20+18+16+14+12+10) x $5 = 90 x $5 = $450 . What’s your cost? 6 x $70 = $420. It’s barely profitable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Should you hire one more employee? That additional employee costs you $70, but only brings in 8 x $5 = $40 in revenue. You’d be losing money on him. DON’T HIRE HIM. Or if you already hired him, then fire him and give him a good job reference. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let’s back up and see if it makes sense to keep employee number 6 around. His marginal cost is $70, and he brings in marginal revenue of 10 x 5= $50. He’s losing money for you also. You don’t want him on your staff. | ||

| + | |||

| + | How about employee number 5? His marginal cost is $70, and he brings in marginal revenue of 12 x 5 = $60. He’s losing money for you also. Fire him too. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Your firm hires four workers and no more. Anyone beyond your fourth employee is a money-loser for you. This is because there is a declining marginal product of labor. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Review== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Monopoly is a single seller. | ||

| + | <br>Monopsony is a single buyer. | ||

| + | <br>If the firm is competitive, then marginal factor cost (MFC) of labor equals the wage of the extra worker: MFC = W. | ||

| + | <br>What is the benefit of that extra worker? Marginal benefit (MB) of L is P x MP (price times marginal product). | ||

| + | <br>What, then, is the marginal profit of hiring one more worker ? It is (P x MP) - W. | ||

| + | <br>So when does a competitive firm hire an additional worker? When P x MP exceeds W. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Labor demand: | ||

| + | :If Q increases, then labor demand increases. | ||

| + | :What causes Q to increase? Increased demand by consumers | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''For Honors only'': what is the effect of consumer demand for output on the labor demand by the company? When consumer demand (demand for output) is more elastic, then labor demand by a company tends to be more elastic. When it is easy to substitute other inputs for labor (such as machines replacing humans), then labor demand also tends to be more elastic. Finally, when other inputs are in more elastic supply, then labor demand tends to be more elastic. And don’t worry if you don’t understand all that yet! | ||

==Economic Rent== | ==Economic Rent== | ||

| Line 156: | Line 225: | ||

(4) Economic rent is the payment of a factor of production in excess of the factor’s opportunity cost or supply cost. | (4) Economic rent is the payment of a factor of production in excess of the factor’s opportunity cost or supply cost. | ||

| − | This is one of the most complex concepts of the course. But this should help: economic rent is the amount that a monopoly can charge in excess of the good’s cost. Economic rent is the surplus enjoyed by the | + | This is one of the most complex concepts of the course. But this should help: '''''economic rent is the amount that a monopoly can charge in excess of the good’s cost'''''. Economic rent is the surplus enjoyed by the seller, at the expense of the person paying it. |

Suppose there is only one house on a peninsula overlooking the ocean out of both sides of the house. The economic rent is the excess in price that the owner can charge due its unique location. The supply is one, and anyone determined to have that house must pay whatever price is charged. Of course, the Law of Demand places a limit on the rent, because people can’t pay what they don’t have, nor will they pay more than what they value something at. But the overcharge due to the uniqueness of the good is what constitutes the “economic rent.” | Suppose there is only one house on a peninsula overlooking the ocean out of both sides of the house. The economic rent is the excess in price that the owner can charge due its unique location. The supply is one, and anyone determined to have that house must pay whatever price is charged. Of course, the Law of Demand places a limit on the rent, because people can’t pay what they don’t have, nor will they pay more than what they value something at. But the overcharge due to the uniqueness of the good is what constitutes the “economic rent.” | ||

| Line 162: | Line 231: | ||

==Economic Profits== | ==Economic Profits== | ||

| − | Remember that “economic profits” include far more than ordinary “accounting profits” or “profits” in the ordinary sense of the term. “Economic profits” are total revenues minus costs that include opportunity costs, time value of money, and other hidden costs missing from most | + | Remember that “economic profits” include far more than ordinary “accounting profits” or “profits” in the ordinary sense of the term. “Economic profits” are total revenues minus costs that include opportunity costs, time value of money, and other hidden costs missing from most statements about profits. Economic profits are much harder to come by. |

| − | Who enjoys true economic profits? Monopolies do, because they can increase their price and reap economic rents. | + | Who enjoys true economic profits? Monopolies do, because they can increase their price and reap economic rents. Apple garners hefty profits year after year for its patented designs on the iPhone, with no end in sight. But ultimately all monopolies, even Apple and Microsoft, fall prey to competition and those economic profits dry up. |

| − | Inventors and other innovators can enjoy real economic profits. Thomas Edison did, with his numerous marvelous patented inventions. Patents give the holder an exclusive right to the product for | + | Inventors and other innovators can enjoy real economic profits. Thomas Edison did, with his numerous marvelous patented inventions. Patents give the holder an exclusive right to the product for 20 years. Competition is prevented for that time, and enormous economic profits can be obtained without competition driving the price down. AT&T used Alexander Graham Bell’s patent on the telephone to build a highly profitable company for a century. But ultimately its economic profits dried up, too. |

| + | |||

| + | ===Honors: Is "economic rent" the same as "deadweight loss"?=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Is "economic rent" (the extra amount charged by a company above its costs, perhaps because it is a monopoly) the same as the "deadweight loss" to society? The answer is "yes": "economic rent" is a type of deadweight loss. Any time the price of a good is raised above its price in a perfectly competitive market, there will be buyers who will not pay the higher price and thus will lose out on the consumer surplus between the higher price and lower, competitive price. That loss in consumer surplus is a deadweight loss. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When the price is increased due to taxes, then both the buyers and the sellers lose out, and there is a deadweight loss that is even greater because it includes both a consumer surplus lost by the buyer and a producer surplus lost by the seller. So while higher prices due to monopolies are bad, higher prices due to taxes are even worse. You could review Lecture 7 and its graph to understand this further. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To show you how recent the theories of economics are, the term "rent seeking" behavior was introduced only 40 years ago. It describes actions by firms to increase their prices and obtain economic rent above the free market, competitive price. Such behavior is not good for the public, because it causes a deadweight loss (lost consumer surplus). | ||

==Assignment== | ==Assignment== | ||

| − | Read | + | Read, and reread as needed, the above lecture. Then answer 6 out of 7 questions below: |

| + | |||

| + | 1. Briefly define each of these terms: monopsony, economic rent, and economic profits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. Define, in your own words, what a "production possibilities curve" is. | ||

| − | + | 3. Review: how is the elasticity of demand for labor related to the price elasticity of demand for the product of that labor? | |

| − | + | 4. Do you think that government policy should give high priority to the Lorenz curve? Explain the issue that a Lorenz curve addresses, and whether you think that should be a high priority of government economic policy. | |

| − | + | 5. Look again at Figure A (on p.3). What is the opportunity cost of shifting production from B to C? | |

| − | + | 6. Review: explain again what AFC, AVC and ATC are, and how they relate to each other. When should a firm shut down in the short run? | |

| − | + | 7. What is needed to reach point D in Figure A (on p.3)? (In other words, what causes a production possibilities curve to shift outward?) | |

| − | + | ===Honors:=== | |

| − | + | Answer 3 out of 4 questions below: | |

| − | + | 8. Look again at Figure C (on p.1) in the lecture (the first graph in this Lecture). At what point is total revenue maximized? | |

| − | + | 9. Explain why the production possibilities curve is convex (opening downward like the top of a circle) rather than concave (opening upward like the inside of a bowl) or a straight line. | |

| − | 9. | + | 10. Suppose you are a monopsony, and you must pay $9 per hour ($9/hr) to hire nine workers, but in order to hire one more worker you must pay $10/hr. The tenth worker will bring in $15 extra per hour to the firm’s revenue. Do you hire the tenth worker? |

| − | + | 11. In the term "comparative advantage," to what does the adjective "comparative" refer? What is the term actually "comparing"? Explain. | |

| − | + | == References == | |

| + | <references/> | ||

[[Category:Economics lectures]] | [[Category:Economics lectures]] | ||

| − | {{DEFAULTSORT: Economics Lecture | + | {{DEFAULTSORT: Economics Lecture 11}} |

Latest revision as of 17:34, May 13, 2013

Economics Lectures - [1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 8 - 9 - 10 - 11 - 12 - 13 - 14]

On the CLEP exam, slightly less than 10% of the questions are about graphs. To answer them correctly, it helps not to be overwhelmed or give up too quickly. The questions simply test and retest a few basic principles in economics. A favorite topic of graphical questions concerns where a monopolist sets his price.

A monopolist has no supply curve, because he is the only supplier. There is only a demand curve, a marginal revenue curve, and some cost curves for a monopolist. If given a graph with these curves, simply find where the marginal revenue curve intersects the marginal cost curve, and that determines the quantity sold.

On the graph to the right (Figure C), there is no supply curve so you know that this represents a monopolist. A typical question is to ask you where the monopolist sets his price in order to maximize his profits. To find this price point, recall that a monopolist sets his price where MC=MR. The graph gives you curves for both MC and MR, so find where they intersect: point A. But that point gives you the quantity supplied, not the price demanded. To find the demand price at the quantity supplied, you have to find the corresponding price point on the demand curve. You trace a line vertically from point A to find the price on the demand curve: point D in Figure C.

That is the answer to a question about where a monopolist sets his price, but that is not the best price for the public. It is higher than the price the public would enjoy if the market were fully competitive. Another question on a CLEP exam might ask where the competitive price would be, also known as the "allocatively efficient" price because it represents the most efficient allocation of resources. That price (and quantity) is where the MC curve intersects the demand curve: point B in Figure C.

Figure C also has a curve for average total cost (ATC). Recall that a firm shuts down in the long run when ATC>P; and the firm shuts down in the short run when AVC>P, but keeps operating in the short run when AVC<P<ATC. This is because "variable cost" is a short run issue, while "total cost" is a long run issue. Does the firm in Figure C shut down? No, because we determined above that the monopolist can sell at point D, and there ATC=P. He is covering (paying for) all his costs. The firm can continue in business.

Here are some other common graphical questions:

- optimal market price: where the supply curve intersects the demand curve. A monopolist has no supply curve and it sells at MC=MR, which has a price higher than the optimal price of MC=P.

- consumer surplus (the benefit to the consumer where the demand curve is higher than price paid, because the consumers pay less than they were willing to pay, as when you would have paid $15 to see a movie but the charge was only $10: your consumer surplus is $5)

- deadweight loss: the lost consumer surplus explained above AND (in the case of a tax) the lost producer surplus (benefit to the seller who was willing to produce at a price less than what he sold it for)

See the graph near the end of Lecture 7 for an explanation of both the consumer and producer surplus, which are also useful in determining the graphical region for the deadweight loss.

Contents

Government Policy

As mentioned in a prior Lecture, 10% of the CLEP exam is on government policy. In addition what we have already learned, we need to know:

- market distribution of income (Lorenz curve)

- market failure and imbalances in information

The Lorenz curve (also known as the Lorenz diagram) is a graph displaying a comparison of the actual distribution of income in a society against a hypothetical equal distribution of income. This could be done by plotting the percent of overall income on the y-axis and the percent of families on the x-axis. A hypothetical (imaginary) equal distribution of income would be a straight line at 45 degrees (the line y=x). But the actual distribution of income would not rise as quickly as that straight line. Going from the poorest 0% to perhaps 20% (on the x-axis) of families would have almost no increase in cumulative income (on the y-axis), and beyond that the slope of the curve for actual income would gradually increase until the richest earners near the top 100% of families were included.

On the CLEP exam, a question about the Lorenz curve will likely seek an answer that government should try to equalize the income distribution in society.

Not everyone agrees. Churches once played a bigger role in "sharing the wealth," and they did it better than government does. Do we want government to replace churches? Of course not.

But government may have a proper role in correcting for imbalances in information, in order to make sure that people have a better understanding of what they are buying. Food products are required by government to disclose their contents, and how much fat they contain. Cigarette companies are required to say that their product causes cancer and hurts people. In some states abortionists are required to disclose some of the harm that abortion causes. Government regulations that improve the knowledge of the public may be beneficial, and may even help reduce negative externalities.

Sometimes markets fail to work entirely, as when competition disappears and there is only one supplier. Imagine the only gas station in town after a hurricane wipes out all his competitors. Or when the biggest banks fail, all at once. The "bail out" before the 2008 elections was an example of government trying to prevent a total market failure. Many disagree with government interference in cases of "market failure," however. What's your view?

Production Possibilities

Nearly 5% of CLEP exam is devoted to questions about "production possibilities." These are easy questions to answer.

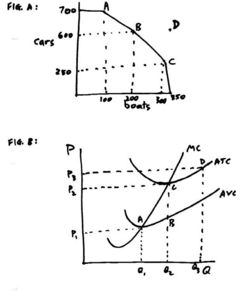

"Production possibilities," or "Possibilities of production," mean all the different combinations of goods a nation can produce. The United States can produce X cars and Y trucks, for example. Or it could produce more than X cars and fewer than Y trucks. We could graph the number of cars on the Y-axis and the number of trucks on the X-axis, and draw a “production possibility” curve through all the possible combinations. It would be downward sloping: more trucks mean fewer cars, and vice-versa. The opportunity cost of producing more cars is the loss in production of trucks. In the production possibility curve for cars and boats shown in Figure A (below), the opportunity cost of moving from point A to point B is 100 cars.

The shape of the production possibilities curve (often called the "production possibilities frontier") is dictated by the high opportunity cost of trying to convert an entire nation's factories from making one type of good to making another type. Imagine having a car factory and a truck factory, and then trying to convert the entire truck factory such that it makes only cars. At a fixed level of expense, the truck factory is not going to be able to make as many cars as the trucks it was designed to make. So converting the nation from, for example, a level of 500 cars and 500 trucks to as many cars as possible will probably not be able to reach a level of 1000 cars and zero trucks. Instead, it will probably top off at a number less than 1000, and hence the tapering of the production possibilities curve near the two axes.

If the overall number of workers or investment capital increased, then you could produce more of everything. The entire production possibilities graph (or “production possibilities frontier”) would shift upward and to the right. An improvement in technology would have the same effect. An increase in bureaucracy or administrative costs, however, would have the opposite effect, forcing a contraction in overall production.

There are several assumptions made in constructing a production possibilities frontier. These assumptions are more realistic in the short run than in the long run:

- there are only two goods, and production is a trade-off between the goods: making more of one means making less of the other.

- there is no increase in waste or regulation; if there is new waste or costly regulation, then the point of production moves to somewhere inside the curve rather than on it.

- the same fixed resources are used for making the same two goods, and technology does not improve

- there is "full employment," such that adding workers requires taking them away from another task

If there are inefficiencies in a nation's economy, then its production will be inside the production possibilities curve. Due to the inefficiencies, the nation will not be producing as much as it could if it were efficient. Just as an increase in capital or an improvement in technology can cause an increase in the production of all goods, an increase in a nation's efficiency can cause its production to increase for all goods, from a point inside the production possibilities curve to a point on the curve.

Sometimes in politics the trade-off between producing goods is described as “guns versus butter.” The more guns (e.g., military weapons) we make, the less butter (e.g., food and domestic services) we can produce. The idea is that there is a trade-off between spending money on our military and spending it on domestic goods and services.

On a personal level, it is usually impossible to do two things at once. Either you spend the next hour working on this course, or you spend it doing something else. You could graph a production possibility curve for how you spend 24 hours each day. It could be 8 hours sleeping, 1 hour exercising, 1 hour traveling to destinations, 3 hours cooking and eating, 6 hours studying, 1 hour relaxing, and 4 hours working at a job. If you take an hour away from one activity, then you can add it to another. Your production possibility curve would represent all the possibilities.

Review: Cost Measures

Consider Figure B to the above right. In order to master economics, develop a habit of asking yourself what you would do if you were the owner of a firm with these costs. Ask yourself: if your output is selling at a price of P1, are you making a profit?[1] Should you stay in business?[2]

Next consider if your output is selling at a price of P2. Are you making a profit there?[3] Should you stay in business?[4]

Finally consider what to do if your output is selling at a price P3. Are you making a profit at that price point?[5] Should you stay in business?[6]

The Law of Comparative Advantage

There is an interesting concept in economics known as the Law of Comparative Advantage. The CLEP exam usually asks two questions about it.

The Law of Comparative Advantage states that if one nation can produce two goods more efficiently than another nation, then the first nation should devote all its resources to producing the good that it makes more efficiently, and let the other nation produce the second good, and then trade one for the other. This Law can apply to individuals and firms as well as countries.

Note that this is not what you might first expect. You might expect the first nation to produce BOTH goods, since it can produce both goods more efficiently than the other nation. But upon closer examination it becomes clear that by focusing on what it does best, and produces more efficiently, the first nation can produce more and then trade for the rest, and be better off. Put another way, "do what you do best!"

In sports, sometimes an athlete is good at one sport (e.g., baseball) but great at another sport (e.g., football). John Elway and Deion Sanders, for example were great at football but only good at baseball. John Elway did what he did best: he played only professional football, and became one of the greatest quarterbacks ever. Deion Sanders played both football and baseball, and perhaps did not achieve as much at either as he could have by focusing what he did best.

Economists observe that utilizing the Law of Comparative Advantage can improve the production possibilities. Suppose your job paid you $9 but you could hire a cook for $6. Then it might make sense for you to work one more hour and hire someone to save you one hour of cooking. In the absence of taxes, you would be $3 better off. Then you could work one-third of an hour less to make the same money (after expenses) as before. That extra one-third of an hour could be added to your sports or relaxation time. You have moved your “production possibilities frontier” (the curve of all possibilities) outward, for greater benefit.

Example

Suppose this is how much in resources it costs the Yankees and Mets to produce great pitchers or outfielders:

| Yankees | Mets | ||

| outfielders | 10 resource units | 5 resource units | |

| pitchers | 9 resource units | 3 resource units |

Even though the Mets can produce outfielders more efficiently than the Yankees can, the Mets are better off spending all their resources developing pitchers and then trading with the Yankees to obtain outfielders.

David Ricardo (1772-1823), one of the greatest classical (conservative) economists, first developed the Law of Comparative Advantage. Note that "comparative advantage" is not the same as "competitive advantage," which simply means something that gives you an advantage in competition over someone else, such as a better location for your gas station.

Review: Inputs

Often we have focused on the OUTPUT of a firm. How many goods will it sell at what price? The price elasticity of its demand, for example, looks at how demand for its output changes based on a change in its price.

Marketing and sales also focus on the output of a company. Marketing consists of advertising and promoting the goods. Sales, the most important aspect of almost any company, consist of persuading customers to buy the company’s good or service. The most valued employees of almost any company are its top salesmen and saleswomen. They are the ones that bring in the money to the company.

If we were to hold a dinner with a speaker, the output would consist of the seats at the dinner and the sales effort consists of selling the spots and receiving money in return. In a homeschool course, the output is the lectures and the sales effort consists of selling places in the course. Colleges, in turn, compete for students who can pay their tuition and fees. Many colleges struggle because they have a difficult time attracting enough students to pay tuition. In fact, very few new colleges have started in the past twenty years, and the new ones have been more conservative than the older ones.

There is another side to every company: its own inputs and the costs they incur. For a bus trip to D.C., the inputs are the cost of the buses and perhaps some food costs. Lowering the costs of those inputs makes the project more affordable.

This is like offense and defense in sports. The people on offense are the salesmen, trying to score points. The people on defense are the buyers of inputs for the company, trying to keep the expenses down. They are opposite jobs, often requiring opposite personalities. Extravagant people make for better salesmen; frugal people are often better buyers of inputs for a company.

Experienced businessmen will emphasize that profits are made by keeping expenses down. After all, profits are the main goal of a typical business. If a company is buying food from supplier number one and can reduce costs by going to supplier number two, then the rational action is to change suppliers from number one to number two.

Keeping costs down was what made Wal-Mart so powerful. Its marketing and advertising have only been mediocre. But it is the best in reducing costs. It pays its employees relatively little; it opposes unions forming among its workers; and it is ruthless in bargaining down the costs of its suppliers. Wal-Mart has made immense profits as a result.

Does that seem unfair? No one has to supply Wal-Mart goods at a low price. If a supplier does not want to do business with Wal-Mart, then it doesn’t have to. No one has to take a job there either!

In general, the demand for inputs by firms is called the “derived demand for inputs,” because it is derived from the consumer demand for the products the company sells. Because your family wants to buy gas from a gas station, this demand creates a demand by the gas station for its inputs: the gas and labor.

Review: Monopsony

A monopsony means only one buyer. It occurs when one buyer holds a monopoly on all purchases.

The best example of a monopsony is when there is only one employer (only one "buyer" of labor) in a small, isolated town. If you want a job in that town, then your only place to work is at that company. Of course, very few towns are actually limited to just one employer. But for a certain type of job, there may be only one employer, and it has a monopsony over that type of job.

A monopsony is different from a competitively hiring firm in one significant way. When a monopsony needs to hire an additional worker, then it has to raise the wages for all its workers to that higher wage level in order to hire an additional worker. Its marginal cost for paying for this "factor" (labor), also known as its marginal factor cost (“MFC”), is more than the wage of merely the one additional worker. MFC equals the W of the additional worker PLUS the increased wage of all the other workers.

For example, if a monopsony can hire 10 workers at $6 or 11 workers at $7, then its MFC of hiring an 11th worker is $7 + (10 x ($7-$6)) = $17.

For a competitive firm, in contrast, MFC=W because it can hire all the workers it needs at the market wage, without causing the market wage to rise for all its workers.

This example helps us understand why the marginal revenue (MR) for a monopoly (one seller) when it increases its price is not the same as the price P of the additional good that it sells. When a monopoly raises its price to obtain more revenue (and more profits), it raises its price on ALL its goods. MR for that increase in price is not simply P, but it is the increased price on all its goods times the quantity of those goods. A monopoly sells where MC=MR, but that is not the same place as where MC=P, because MR does not equal P for a monopoly. MR does equal P for a perfectly competitive firm.

Honors: Example

Let’s start with this simple equation: Profits = Total revenue - Total cost. That’s easy enough. Now let’s break it down, where P=Price, Q=Quantity, W=Wage, and L=Labor units:

- Profits = (P x Q) - (W x L) - other non-labor input costs

Now suppose we add one more worker to our company. We will have to pay him a wage of W, so the marginal factor cost of one more worker is W (assuming a competitive market). What is his marginal benefit to our company? It is P x MP.

When does a company hire that additional worker? When the change in profit is greater than zero. That occurs when (P x MP) > W.

Example: suppose a firm has a declining marginal product for each additional laborer hired, such that:

| Labor Units (L) | Marginal Product (MP) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 20 |

| 2 | 18 |

| 3 | 16 |

| 4 | 14 |

| 5 | 12 |

| 6 | 10 |

| 7 | 8 |

Suppose the wage W for each employee is $70 and the price the output is sold for is $5. How many workers should you hire?

If you hired just one employee, then you would make 20 x $5 = $100 in revenue. But your cost was only W=$70, so you made a profit of $30! You’ll hire at least one employee.

If you hire a second employee, then you would make (20+18) x $5 = $190. But your cost was only $70 x 2 = $140, so your profit is $50! You’re doing even better, so you hire the second employee.

Skip down to hiring employee number 6. Then you make (20+18+16+14+12+10) x $5 = 90 x $5 = $450 . What’s your cost? 6 x $70 = $420. It’s barely profitable.

Should you hire one more employee? That additional employee costs you $70, but only brings in 8 x $5 = $40 in revenue. You’d be losing money on him. DON’T HIRE HIM. Or if you already hired him, then fire him and give him a good job reference.

Let’s back up and see if it makes sense to keep employee number 6 around. His marginal cost is $70, and he brings in marginal revenue of 10 x 5= $50. He’s losing money for you also. You don’t want him on your staff.

How about employee number 5? His marginal cost is $70, and he brings in marginal revenue of 12 x 5 = $60. He’s losing money for you also. Fire him too.

Your firm hires four workers and no more. Anyone beyond your fourth employee is a money-loser for you. This is because there is a declining marginal product of labor.

Review

Monopoly is a single seller.

Monopsony is a single buyer.

If the firm is competitive, then marginal factor cost (MFC) of labor equals the wage of the extra worker: MFC = W.

What is the benefit of that extra worker? Marginal benefit (MB) of L is P x MP (price times marginal product).

What, then, is the marginal profit of hiring one more worker ? It is (P x MP) - W.

So when does a competitive firm hire an additional worker? When P x MP exceeds W.

Labor demand:

- If Q increases, then labor demand increases.

- What causes Q to increase? Increased demand by consumers

For Honors only: what is the effect of consumer demand for output on the labor demand by the company? When consumer demand (demand for output) is more elastic, then labor demand by a company tends to be more elastic. When it is easy to substitute other inputs for labor (such as machines replacing humans), then labor demand also tends to be more elastic. Finally, when other inputs are in more elastic supply, then labor demand tends to be more elastic. And don’t worry if you don’t understand all that yet!

Economic Rent

There are four equivalent definitions of “economic rent.” Pick the one you like the best and then use it to understand the others:

(1) Economic rent is the increased payment for a (scarce) good due to its very limited supply.

(2) Economic rent is the amount that a payment exceeds the supply cost. The “rent” is the excess of a good’s actual price above the good’s supply cost.

(3) Economic rent is the increased payment for an input that is in perfectly inelastic supply.

(4) Economic rent is the payment of a factor of production in excess of the factor’s opportunity cost or supply cost.

This is one of the most complex concepts of the course. But this should help: economic rent is the amount that a monopoly can charge in excess of the good’s cost. Economic rent is the surplus enjoyed by the seller, at the expense of the person paying it.

Suppose there is only one house on a peninsula overlooking the ocean out of both sides of the house. The economic rent is the excess in price that the owner can charge due its unique location. The supply is one, and anyone determined to have that house must pay whatever price is charged. Of course, the Law of Demand places a limit on the rent, because people can’t pay what they don’t have, nor will they pay more than what they value something at. But the overcharge due to the uniqueness of the good is what constitutes the “economic rent.”

Economic Profits

Remember that “economic profits” include far more than ordinary “accounting profits” or “profits” in the ordinary sense of the term. “Economic profits” are total revenues minus costs that include opportunity costs, time value of money, and other hidden costs missing from most statements about profits. Economic profits are much harder to come by.

Who enjoys true economic profits? Monopolies do, because they can increase their price and reap economic rents. Apple garners hefty profits year after year for its patented designs on the iPhone, with no end in sight. But ultimately all monopolies, even Apple and Microsoft, fall prey to competition and those economic profits dry up.

Inventors and other innovators can enjoy real economic profits. Thomas Edison did, with his numerous marvelous patented inventions. Patents give the holder an exclusive right to the product for 20 years. Competition is prevented for that time, and enormous economic profits can be obtained without competition driving the price down. AT&T used Alexander Graham Bell’s patent on the telephone to build a highly profitable company for a century. But ultimately its economic profits dried up, too.

Honors: Is "economic rent" the same as "deadweight loss"?

Is "economic rent" (the extra amount charged by a company above its costs, perhaps because it is a monopoly) the same as the "deadweight loss" to society? The answer is "yes": "economic rent" is a type of deadweight loss. Any time the price of a good is raised above its price in a perfectly competitive market, there will be buyers who will not pay the higher price and thus will lose out on the consumer surplus between the higher price and lower, competitive price. That loss in consumer surplus is a deadweight loss.

When the price is increased due to taxes, then both the buyers and the sellers lose out, and there is a deadweight loss that is even greater because it includes both a consumer surplus lost by the buyer and a producer surplus lost by the seller. So while higher prices due to monopolies are bad, higher prices due to taxes are even worse. You could review Lecture 7 and its graph to understand this further.

To show you how recent the theories of economics are, the term "rent seeking" behavior was introduced only 40 years ago. It describes actions by firms to increase their prices and obtain economic rent above the free market, competitive price. Such behavior is not good for the public, because it causes a deadweight loss (lost consumer surplus).

Assignment

Read, and reread as needed, the above lecture. Then answer 6 out of 7 questions below:

1. Briefly define each of these terms: monopsony, economic rent, and economic profits.

2. Define, in your own words, what a "production possibilities curve" is.

3. Review: how is the elasticity of demand for labor related to the price elasticity of demand for the product of that labor?

4. Do you think that government policy should give high priority to the Lorenz curve? Explain the issue that a Lorenz curve addresses, and whether you think that should be a high priority of government economic policy.

5. Look again at Figure A (on p.3). What is the opportunity cost of shifting production from B to C?

6. Review: explain again what AFC, AVC and ATC are, and how they relate to each other. When should a firm shut down in the short run?

7. What is needed to reach point D in Figure A (on p.3)? (In other words, what causes a production possibilities curve to shift outward?)

Honors:

Answer 3 out of 4 questions below:

8. Look again at Figure C (on p.1) in the lecture (the first graph in this Lecture). At what point is total revenue maximized?

9. Explain why the production possibilities curve is convex (opening downward like the top of a circle) rather than concave (opening upward like the inside of a bowl) or a straight line.

10. Suppose you are a monopsony, and you must pay $9 per hour ($9/hr) to hire nine workers, but in order to hire one more worker you must pay $10/hr. The tenth worker will bring in $15 extra per hour to the firm’s revenue. Do you hire the tenth worker?

11. In the term "comparative advantage," to what does the adjective "comparative" refer? What is the term actually "comparing"? Explain.

References

- ↑ No.

- ↑ No, because the price is less than both AVC and ATC.

- ↑ You are making a daily profit because P>AVC, but losing money when all your fixed costs are included because P<ATC.

- ↑ Yes, because P>AVC so you are making a marginal profit, but not covering all your original costs.

- ↑ Yes.

- ↑ Yes, absolutely. Your price is greater than both your ATC and AVC. You're making good money at this price point for your output. (But note that output is not at Q3 in the graph, but is where MC=P3.)