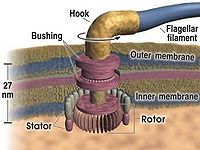

A flagellum is a long, tail-like organelle in a cell that allows a cell to move around. It is made up of microtubules and surrounded by a plasma membrane.

In single-cell organisms flagella move like a whip to provide propulsion to the cell. As part of a larger organism, their function is often to move fluids along mucous membranes. When they perform this function, they are called cilia.

There are three types of flagella: eukaryotic, archaeal and bacterial.

The internal structure of eukaryotic flagella is made up of nine microtubule doublets linked by proteins, which form a cylinder around a central pair of microtubules. There are usually only one or two flagella on a eukaryotic cell, and they move in a lashing motion like a whip. One example of this is the [sperm] cell.

Bacterial flagella have threads in a helix pattern, that rotate rather like a screw to move the organism.

Bacterial Flagellum and Intelligent Design

The bacterial flagellum has frequently been presented as a counter-example to the theory of evolution.[1][2] Intelligent design theorists argue that it could not possibly have been produced by an evolutionary pathway.

Intelligent design theorist Willam Dembski wrote:

| “ | In a 1996 review of Michael Behe’s book Darwin's Black Box, James Shapiro, a molecular biologist at the University of Chicago, wrote: "There are no detailed Darwinian accounts for the evolution of any fundamental biochemical or cellular system, only a variety of wishful speculations. It is remarkable that Darwinism is accepted as a satisfactory explanation for such a vast subject -- evolution -- with so little rigorous examination of how well its basic theses work in illuminating specific instances of biological adaptation or diversity" (National Review, 16 September 1996). Five years later cell biologist Franklin Harold wrote a book for Oxford University Press titled The Way of the Cell. In virtually identical language, he notes: "There are presently no detailed Darwinian accounts of the evolution of any biochemical or cellular system, only a variety of wishful speculations."[3] | ” |

The argument from irreducible complexity

The flagellum is said to possess "irreducible complexity," meaning it could not have been produced by evolution. This argues for an outside intelligent designer operating beyond the laws of nature. Behe defines an irreducibly complex structure as ". . . a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning." [4]

Behe asserts that the flagellum is a structure "in which the removal of an element would cause the whole system to cease functioning" [5] and that its individual parts must have been specifically designed to work as a unified assembly.

The argument is that because a minimum number of protein components are needed for a working biological function, evolution could not have selected to produce those components a few at a time, since they do not have functions that natural selection would favor. The logic of irreducible complexity dictates that these individual components should have no function until all 30 are put into place, at which point the function appears. Behe wrote: " . . . natural selection can only choose among systems that are already working".[6] An irreducibly complex system does not work unless all of its parts are in place. The flagellum is irreducibly complex, and therefore it must have been designed.

The Combinatorial argument

William Dembski [7] calculated the probability of assembling an object like the flagellum by working out the probabilities that each of its components might have originated, been localized to the same region of the cell, and assembled in the right order by chance.

Dembski states that, given enough time, any event with a probability larger than 10-150 might well take place. He puts the odds of evolving the 30 proteins of the bacterial flagellum at 20-30 ("around 10-39") and explains that since the flagellum requires 30 such proteins, they "will all need to be multiplied to form the origination probability", which would give an origination probability for the flagellum of 10 -1170. This is well below the universal probability bound, demonstrating, in his view, that the flagellum could not have evolved.

References

- ↑ Dembski, W. 2002a, No Free Lunch: Why specified complexity cannot be purchased without intelligence. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- ↑ Behe, M. 1996a. Darwin's Black Box. New York: The Free Press.

- ↑ http://www.designinference.com/documents/2002.07.kurzweil_reply.htm

- ↑ Behe, M. 1996a. Darwin's Black Box. New York: The Free Press.

- ↑ Behe, M., 2002. The challenge of irreducible complexity, Natural History 111 (April): 74.

- ↑ Behe, M., 2002. The challenge of irreducible complexity, Natural History 111 (April): 74.

- ↑ Dembski, W. 2002a, No Free Lunch: Why specified complexity cannot be purchased without intelligence. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.