Difference between revisions of "General theory of relativity"

m |

(Intro to the metric tensor) |

||

| Line 358: | Line 358: | ||

With these two assumptions and this convenient property in hand, we will now examine what it means to say that spacetime is curved. | With these two assumptions and this convenient property in hand, we will now examine what it means to say that spacetime is curved. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Flatness versus curvature==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Let's start by considering the simplest possible geometry<ref>Well, the simplest possible ''interesting'' geometry, anyway.</ref>: the [[Euclidean plane]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Euclidean plane is an infinite, flat, two-dimensional surface. A sheet of paper is a good approximation of the Euclidean plane. Onto this plane, we can project a set of [[Cartesian coordinates]]. By "Cartesian," we mean that the coordinate axes are straight lines, that they are perpendicular, and that the unit lengths of the axes are equal. A fancier term for a Cartesian coordinate system is an ''orthonormal basis.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note carefully the distinction between the Euclidean plane and Cartesian coordinates. The plane exists as a thing in and of itself, just as a blank piece of paper does. It has certain properties, which we'll get into below. Those properties are ''intrinsic'' to the plane. That is, the properties don't have anything to do with the coordinates we project onto the plane. The plane is a geometric object, and the coordinates are the method by which we ''measure'' the plane. (The emphasis on the word ''measure'' there is not accidental; please keep this idea in the foreground of your mind as we continue.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cartesian coordinates are not the only coordinates we can use in the Euclidean plane. For example, instead of having axes that are perpendicular to each other, we could choose axes that are straight lines, but that meet at some non-perpendicular angle. These types of coordinates are called ''oblique.'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | For that matter, we're not bound to use straight-line coordinates at all. We could instead choose [[polar coordinates]], wherein every point on the plane is described by a distance from a fixed but arbitrary point and an angle from a fixed but arbitrary direction. Polar coordinates are often more convenient than Cartesian coordinates. For example, when navigating a ship on the ocean, the location of a fixed point is usually described in terms of a ''bearing'' and a ''distance,'' where the distance is the straight-line distance from the ship to the point, and the bearing is the clockwise angle relative to the direction in which the ship is sailing. Polar coordinates in two and three dimensions are often used in physics for similar reasons. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But there's a fundamental problem with polar coordinates that is not present with Cartesian coordinates. In Cartesian coordinates, every point on the Euclidean plane is identified by ''exactly one'' set of real numbers: there is precisely one set of <math>x</math> and <math>y</math> coordinates for every point, and every point corresponds to precisely one set of coordinates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is not true in polar coordinates. What are the unique polar coordinates for the origin? The radial distance is obviously zero, but what is the angle? In actuality, if the radial distance is zero, ''any'' angle can be used, and the coordinates will identify the same point. The one-to-one correspondence between points in the plane and pairs of coordinates breaks down at the origin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In mathematical terms, polar coordinates in the Euclidean plane have a ''coordinate singularity'' at the origin. A coordinate singularity is a point in space where ambiguities are introduced, not because of some intrinsic property of space, but because of the coordinate basis you chose. | ||

| + | |||

| + | So clearly there may exist a reason to choose one coordinate system over another when ''measuring'' — there's that word again — the Euclidean plane. Polar coordinates have a singularity at the origin — in this case, a point of undefined angle — while Cartesian coordinates have no such singularities anywhere. So there may be good reason to choose Cartesian coordinates over polar coordinates when measuring the Euclidean plane. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fortunately, this is always possible. The Euclidean plane can ''always'' be measured by Cartesian coordinates; that is, coordinates wherein the axes are straight and perpendicular at their intersection, and where ''lines of constant coordinate'' — picture the grid on a sheet of graph paper — are always a constant distance apart no matter where you measure them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Imagine taking a piece of graph paper, which is printed in a pattern that lets us easily visualize the Cartesian coordinate system, and rolling it into a cylinder. Do any creases appear in the paper? No, it remains smooth all over. Do the lines printed on the paper remain a constant distance apart everywhere? Yes, they do. In technical mathematical terms, then, the surface of a cylinder is ''flat.'' That is, it can be measured by an orthonormal basis, and there is everywhere a one-to-one correspondence between sets of coordinates and points on the surface. It's possible ''not'' to use an orthonormal basis to measure the surface; one might reasonably choose polar coordinates, or some other arbitrary coordinate system, if it's more convenient. But whichever basis is actually used, it's always ''possible'' to switch to an orthonormal basis instead. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now imagine wrapping a sheet of graph paper around a basketball. Does the paper remain smooth? No, if we press it down, creases appear. Do the lines on the paper remain parallel? No, they have to bend in order to conform the paper to the shape of the ball. In the same technical mathematical terms, the surface of a sphere is ''not flat.'' It's ''curved.'' That is, it is not possible to measure the surface all over using an orthonormal basis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But what if we focus our attention only on a part of the sphere? What if instead of measuring a basketball, we want to measure the whole Earth? The Earth is a sphere, and therefore its surface is curved and can't be measured all over with Cartesian coordinates. But if we look only at a small section of the surface — a square mile on a side, for instance — then we can project a set of Cartesian coordinates that work just fine. If we choose our region of interest to be sufficiently small, then Cartesian coordinates will fit on the surface to within the limits of our ability to measure the difference. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The surface of a sphere, then, is ''globally curved,'' but ''locally flat.'' In physicist jargon, the surface of a sphere can be ''flattened'' over a sufficiently small region. Not the whole sphere all at once, nor half of it, nor a quarter of it. But a sufficiently small region can be dealt with as if it were a Euclidean plane. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But this brings up an important point. The ''entire'' surface of the sphere is curved, and thus can't be approximated with Cartesian coordinates. But a sufficiently ''small'' patch of the surface can be approximated with Cartesian coordinates. This implies, then, that "curvedness" isn't an either-or property. Somewhere between the locally flat region of the surface and the entire surface, the ''amount'' of curvature goes from none to some value. Curvature, then, must be something we can measure. | ||

====The metric tensor==== | ====The metric tensor==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is a fundamental property of the Euclidean plane that, when Cartesian coordinates are used, the distance <math>s</math> between any two points <math>A</math> and <math>B</math> is given by the following equation: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | s^2 = \Delta x^2 + \Delta y^2\, | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>\Delta x</math> and <math>\Delta y</math> are the distance between <math>A</math> and <math>B</math> in the <math>x</math> and <math>y</math> directions, respectively. This is essentially a restatement of the universally known [[Pythagorean theorem]], and in the context of general relativity, it is called the ''metric equation.'' Metric, of course, comes from the same linguistic root as the word ''measure,'' and since this is the equation we use to ''measure'' distances, it makes sense to call it the ''metric'' equation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But this ''particular'' metric equation ''only'' works on the Euclidean plane with Cartesian coordinates. If we use polar coordinates, this equation won't work.<ref>This is trivial to demonstrate. If <math>r</math> is zero and <math>\theta</math> is non-zero, then <math>r^2 + \theta^2</math> will be non-zero for a vector that obviously has no length.</ref> If we're on a curved surface instead of a plane, this equation won't work. This metric equation is ''only'' valid on a ''flat'' surface with ''Cartesian'' coordinates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Which makes it pretty useless, since so much of physics revolves around curved spacetime and spherical coordinates. | ||

| + | |||

| + | What we need is a ''generalized'' metric equation, some way of measuring the interval of any two points regardless of what coordinate system we're using or whether our local geometry is flat or curved. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ''metric tensor equation'' provides this generalization. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If <math>v</math> is any vector having components <math>v^\mu</math>, the length of <math>v</math> is given by the following equation: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | s^2 = g_{\mu\nu} v^{\mu} v^{\nu}\, | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | where <math>g_{\mu\nu}</math> is the ''metric tensor,'' and <math>\mu</math> and <math>\nu</math> range over the number of dimensions. Recall that Einstein summation notation means that this is actually a sum over indices <math>\mu</math> and <math>\nu</math>. If we assume that we're in the two-dimensional Euclidean plane, the metric tensor equation expands to: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | s^2 = g_{11} v^{1} v^{1} + g_{12} v^{1} v^{2} + g_{21} v^{2} v^{1} + g_{22} v^{2} v^{2}\, | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The terms of the metric tensor, then, must be numerical coefficients in the metric equation. We already know what these equations need to be to make the metric equation work in the Euclidean plane with Cartesian coordinates: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | s^2 = (1) v^{1} v^{1} + (0) v^{1} v^{2} + (0) v^{2} v^{1} + (1) v^{2} v^{2}\, | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we can write the metric tensor for the Euclidean plane in Cartesian coordinates in the form of a 2 × 2 matrix: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | g_{\mu\nu} = \begin{pmatrix} | ||

| + | 1 & 0 \\ | ||

| + | 0 & 1 | ||

| + | \end{pmatrix} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | So in the case of the Euclidean plane with Cartesian coordinates, the metric tensor is the [[Kronecker delta]]: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | \delta^i_j = \begin{cases} | ||

| + | 1, & \mbox{if }i = j \\ | ||

| + | 0, & \mbox{if }i \ne j | ||

| + | \end{cases} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Of course, the same concepts apply if we expand our interest from the plane to three-dimensional Euclidean ''space'' with Cartesian coordinates. We just have to let the indices of the Kronecker delta run from 1 to 3. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | g_{\mu\nu} = \begin{pmatrix} | ||

| + | 1 & 0 & 0\\ | ||

| + | 0 & 1 & 0\\ | ||

| + | 0 & 0 & 1 | ||

| + | \end{pmatrix} | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Which gives us the following metric equation for the length of a vector <math>v</math> (omitting terms with zero coefficient): | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math> | ||

| + | s^2 = (v^1)^2 + (v^2)^2 + (v^3)^2\, | ||

| + | </math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Which precisely agrees with the Pythagorean theorem in three dimensions. So given a metric tensor <math>g_{\mu\nu}</math> for any space and coordinate basis, we can calculate the distance between any two points. The ''metric'' tensor, therefore, is what allows us to ''measure'' curved space. In a very real sense, the metric tensor describes the ''shape'' of both the underlying geometry and the chosen coordinate basis. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But relativity is concerned not with geometrically abstract ''space;'' we're interested in very real space''time,'' and that requires a slightly different kind of metric. | ||

====The local Minkowski metric==== | ====The local Minkowski metric==== | ||

Revision as of 19:44, November 15, 2009

| ! | Apologies This page is undergoing massive reconstruction. You can help, if you have specialized knowledge of the subject matter. Please discuss modifications on the Talk Page. |

|

The General Theory of Relativity is an extension of special relativity, dealing with curved coordinate systems, accelerating frames of reference, curvilinear motion, and curvature of spacetime itself. It could be said that general relativity is to special relativity as vector calculus is to vector algebra. General relativity is best known for its formulation of gravity as a fictitious force arising from the curvature of spacetime. In fact, "general relativity" and "Einstein's formulation of gravity" are nearly synonymous in many people's minds.

The general theory of elativity was first published by Albert Einstein in 1916.

General relativity, like quantum mechanics (the other of the two theories comprising "modern physics") both have reputations for being notoriously complicated and difficult to understand. In fact, in the early decades of the 20th century, general relativity had a sort of cult status in this regard. General relativity and quantum mechanics are both advanced college-level and postgraduate level topics. Hence this article can't possibly give a comprehensive explation of general relativity at the expert level. But we will attempt to give a rough outline, for lay people, of the general relativistic formulation of gravity.

In the weak field approximation, where velocities of moving objects are low and gravitational fields are not very severe, the theory of general relativity is said to reduce to the law of universal gravitation. That is to say, under those circumstances the equations of general relativity are mathematically equivalent to the equations of Newtonian gravitation.

Modern science does not say that Newtonian (classical) gravity is wrong. It is obviously very very nearly correct. In the weak field approximation, such as one finds in our solar system, the differences between general relativity and Newtonian gravity are miniscule. It takes very sensitive tests to show the difference. The history of those tests is a fascinating subject, and will be covered near the end of this article. But in all tests conducted so far, where there are discrepancies between the predictions of general relativity and Newtonian gravity (or other competing theories for that matter), experimental results have shown general relativity to be a better description.

Outside of the solar system, one can find stronger gravitational fields, and other phenomena, such as quasars and neutron stars, that permit even more definitive tests. General relativity appears to pass those tests as well.

This is not to say, by any means, that general relativity is the ultimate, perfect theory. It has never been unified with modern formulations of quantum mechanics, and it is therefore known to be incorrect at extremely small scales. Just as Newtonian gravity is very nearly correct, and completely correct for its time, general relativity is believed to be very nearly correct, but not completely so. Contemporary speculation on the next step involves extremely esoteric notions such as string theory, gravitons, and "quantum loop gravity".

The theory was inspired by a thought experiment developed by Einstein involving two elevators. The first elevator is stationary on the Earth, while the other is being pulled through space at a constant acceleration of g. Einstein realized that any physical experiment carried out in the elevators would give the same result. This realization is known as the equivalence principle and it states that accelerating frames of reference and gravitational fields are indistinguishable. General relativity is the theory of gravity that incorporates special relativity and the equivalence principle.

The general theory of relativity is a metric theory, sometimes also called a geometric theory. Metric theories describe physical phenomena in terms of differential geometry. This stands in contrast to Isaac Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation, which described gravity in terms of a vector field. In the case of general relativity, the theory relates stress-energy — an extension of the concept of mass — and the curvature of spacetime. In the words of physicist John Wheeler, "Space tells matter how to move, matter tells space how to curve."[1]

Contents

- 1 Coordinate Systems and Spacetime Diagrams

- 2 Qualitative Introduction to General Relativity

- 3 Quantitative Introduction to General Relativity

- 3.1 The right side of the equation: the stress-energy tensor

- 3.2 The left side of the equation: the Einstein curvature tensor

- 3.2.1 Some assumptions about the universe

- 3.2.2 Flatness versus curvature

- 3.2.3 The metric tensor

- 3.2.4 The local Minkowski metric

- 3.2.5 Geodesics

- 3.2.6 Parallel transport and intrinsic curvature

- 3.2.7 The Riemann and Ricci tensors and the curvature scalar

- 3.2.8 The Einstein tensor

- 3.2.9 The cosmological constant

- 4 Exact Solutions in General Relativity

- 5 Tests of General Relativity

- 6 Relation to Special Relativity

- 7 External Links

- 8 References

Coordinate Systems and Spacetime Diagrams

Figure 1 shows a "spacetime diagram", with my house, my neighbor's house, and my neighbor walking from his house to mine.

- This is the same kind of diagram that is used in explanations of special relativity. The "spacetime" is sometimes called "Minkowski space". Spacetime is actually four-dimensional, but we can only show two dimensions, so we leave out y and z. The single x spatial coordinate is good enough for our purposes, so the diagram has x going from left to right, and t (time) going upward. For the purposes of this explanation, don't worry about the considerations of special relativity such as the speed of light, the Lorentz transform, or light cones. None of that is important just now.

The diagram shows the calibration, in space (that is, x) and time. These measurements are made with respect to my (stationary) frame of reference. My house is at x=0, and my neighbor's house is at x=1250 (feet). My neighbor walks at 250 feet per minute.

The diagram shows some "events"—my house, now; my house, 5 minutes from now; and my neighbor's house now and 5 minutes from now. The diagonal line depicts my neighbor walking from his house to mine, arriving 5 minutes from now. That line is called his world line. The line going straight up in my house is my own world line (I'm sitting at home.)

A car is driving down the street, from left to right. Figure 2 shows the same four events and two world lines, but with different calibration—the car's own coordinate system. The car is driving 500 feet per minute, but in the opposite direction. The event of my neighbor's arrival at my house is now at x=-2500. It's way behind the car, though the car was directly in front of my house at t=0.

Because the car's frame of reference is in motion, the calibration lines in figure 2 are not perpendicular. The formerly vertical lines are now slanted. But there is something very important to notice about the two coordinate systems: They are flat[2]. The flatness comes from the fact that the calibration lines are straight and parallel. The boxes created by the lines are parallelograms. But note that the lines don't have to be perpendicular, and the boxes don't have to be rectangles. Straight parallel lines and parallelograms are all that is required.

These two flat coordinate systems have a very important physical property: Neither I, sitting at home, nor a passenger in the car, experiences any "fictitious forces". That is, people in the car don't feel any recoil from acceleration, or centrifugal force, or Coriolis force. These frames of reference are said to be inertial. This leads to an important principle of geometrical physics:

- Inertial frames of reference have flat coordinate systems. Flat coordinate systems lead to an absence of fictitious forces.

Now consider figure 3. The coordinate system is once again that of the car, but the car is accelerating, starting at a standstill in front of my house at t=0. Its world line is curved. Once again, it crosses paths with my neighbor. This case is very different from the other two. The calibration lines are curved, and the boxes that they create are not parallelograms. This coordinate system is curved. Another thing to notice is that people in the car will feel a fictitious force—a "recoil" force agains the back of the seat. This frame of reference is not inertial.

- Accelerating frames of reference have curved coordinate systems. Curved coordinate systems lead to fictitious forces.

- .... !!!! We need these three diagrams, of course. I'll do them, but they will take a lot of work. If anyone else has the tools and expertise to do this, and more skill than I, feel free to make them, or to communicate with me (PatrickD).

... In progress ...

Qualitative Introduction to General Relativity

The relationship between the curvature of spacetime and the motions of freely falling bodies is often explained by an easily imagined analogy: bowling balls and golf balls on a trampoline.

Imagine that we place a golf ball on an ordinary backyard trampoline. If we give the golf ball a slight push, it will roll along in a straight line until friction brings it to a halt. But if we imagine that friction doesn't exist, then the golf ball will roll in a straight line at a constant speed forever — or at least until it reaches the edge of the trampoline and falls off.

Now imagine a bowling ball sitting in the middle of a trampoline. The trampoline isn't a rigid surface, so it deforms where the weight of the bowling ball pushes it down. This causes the surface to be curved downward, toward the ground.

If we place a golf ball near the edge of the trampoline, it will begin to roll toward the bowling ball, because the trampoline is sloped downward in that direction. The golf ball will start off moving very slowly, then pick up speed as it approaches the bowling ball, until finally it collides with the bowling ball and comes to rest.

But if we give the golf ball a slight push in a direction perpendicular to the direction of the bowling ball, then it will move in a curved path. If we only push it a little bit, the golf ball will curve slightly, but still collide with the bowling ball. If we push the golf ball somewhat harder, it will curve toward the bowling ball, pass by it on one side and climb back out of the depression until it reaches the edge and falls off.

But if we're very careful, and give the golf ball just the right push, it will curve completely around the bowling ball and return to our hand.

This is, in a nutshell, how spacetime and matter interact under the theory of general relativity. Massive objects — represented in our analogy by the bowling ball — curve spacetime. Less-massive objects also curve spacetime, but to a lesser extent. If the object is small enough, like our golf ball, the amount of curvature is so slight that we can't even measure it.

The way the golf ball moved in the three scenarios we imagined correspond to conic-section orbits, or Kepler orbits. When we just placed the golf ball and it rolled straight toward the bowling ball, that was a degenerate orbit: a straight line. When we gave it a push and it curved around the bowling ball and off the edge of the trampoline, that was a hyperbolic orbit. And when we gave it just the right push so that it curved around the bowling ball and back to our hand, that was an elliptical orbit.

These are the same orbits that are predicted by Isaac Newton's law of universal gravitation. But in Newton's equations, objects move in conic-section orbits because of a force that accelerates them toward the central mass. In general relativity, objects move in conic-section orbits because spacetime itself is curved, just like our imaginary trampoline was curved by the bowling ball.

Of course, our analogy is far from perfect. Our imaginary trampoline curved downward, toward the ground, pushed down by the weight of the bowling ball. That's not how spacetime behaves in general relativity. It curves, but not toward anything, not in any direction. Spacetime in general relativity is instead said to have intrinsic curvature, which is mathematically quite simple but very difficult to visualize.

And of course there are many, many other aspects of general relativity that our imaginary trampoline didn't model. But the analogy captures the essential nature of the theory: the bowling ball caused the trampoline to be curved, and the curvature of the trampoline caused the golf ball to move in a different way than if the trampoline had been flat. This is the essence of general relativity: matter tells space how to curve, and space tells matter how to move.

Quantitative Introduction to General Relativity

|

This article/section deals with mathematical concepts appropriate for a student in late university or graduate level. |

General Relativity is a mathematical extension of Special Relativity. GR views space-time as a 4-dimensional manifold, which looks locally like Minkowski space, and which acquires curvature due to the presence of massive bodies. Thus, near massive bodies, the geometry of space-time differs to a large degree from Euclidean geometry: for example, the sum of the angles in a triangle is not exactly 180 degrees. Just as in classical physics, objects travel along geodesics in the absence of external forces. Importantly though, near a massive body, geodesics are no longer straight lines. It is this phenomenon of objects traveling along geodesics in a curved spacetime that accounts for gravity.

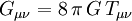

The mathematical expression of the theory of general relativity takes the form of the Einstein field equations, a set of ten nonlinear partial differential equations. While solving these equations is quite difficult, examining them provides valuable insight into the structure and meaning of the theory.

In their general form, the Einstein field equations are written as a single tensor equation in abstract index notation relating the curvature of spacetime to sources of curvature such as energy density and momentum.

In this form,  represents the Einstein tensor,

represents the Einstein tensor,  is the same gravitational constant that appears in the law of universal gravitation, and

is the same gravitational constant that appears in the law of universal gravitation, and  is the stress-energy tensor (sometimes referred to as the energy-momentum tensor). The indices

is the stress-energy tensor (sometimes referred to as the energy-momentum tensor). The indices  and

and  range from zero to three, representing the time coordinate and the three space coordinates in a manner consistent with special relativity.

range from zero to three, representing the time coordinate and the three space coordinates in a manner consistent with special relativity.

The left side of the equation — the Einstein tensor — describes the curvature of spacetime in the region under examination. The right side of the equation describes everything in that region that affects the curvature of spacetime.

As we can clearly see even in this simplified form, the Einstein field equations can be solved "in either direction." Given a description of the gravitating matter, energy, momentum and fields in a region of spacetime, we can calculate the curvature of spacetime surrounding that region. On the other hand, given a description of the curvature of a region spacetime, we can calculate the motion of a test particle anywhere within that region.

Even at this level of examination, the fundamental thesis of the general theory of relativity is obvious: motion is determined by the curvature of spacetime, and the curvature of spacetime is determined by the matter, energy, momentum and fields within it.

The right side of the equation: the stress-energy tensor

In the Newtonian approximation, the gravitational vector field is directly proportional to mass. In general relativity, mass is just one of several sources of spacetime curvature. The stress-energy tensor,  , includes all of these sources. Put simply, the stress-energy tensor quantifies all the stuff that contributes to spacetime curvature, and thus to the gravitational field.

, includes all of these sources. Put simply, the stress-energy tensor quantifies all the stuff that contributes to spacetime curvature, and thus to the gravitational field.

First we will define the stress-energy tensor technically, then we'll examine what that definition means. In technical terms, the stress energy tensor represents the flux of the  component of 4-momentum across a surface of constant coordinate

component of 4-momentum across a surface of constant coordinate  .

.

Fine. But what does that mean?

In classical mechanics, it's customary to refer to coordinates in space as  ,

,  and

and  . In general relativity, the convention is to talk instead about coordinates

. In general relativity, the convention is to talk instead about coordinates  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , where

, where  is the time coordinate otherwise called

is the time coordinate otherwise called  , and the other three are just the

, and the other three are just the  ,

,  and

and  coordinates. So "a surface of constant coordinate "

coordinates. So "a surface of constant coordinate " " simply means a 3-plane perpendicular to the

" simply means a 3-plane perpendicular to the  axis.

axis.

The flux of a quantity can be visualized as the magnitude of the current in a river: the flux of water is the amount of water that passes through a cross-section of the river in a given interval of time. So more generally, the flux of a quantity across a surface is the amount of that quantity that passes through that surface.

Four-momentum is the special relativity analogue of the familiar momentum from classical mechanics, with the property that the time coordinate  of a particle's four-momentum is simply the energy of the particle; the other three components of four-momentum are the same as in classical momentum.

of a particle's four-momentum is simply the energy of the particle; the other three components of four-momentum are the same as in classical momentum.

So putting that all together, the stress-energy tensor is the flux of 4-momentum across a surface of constant coordinate. In other words, the stress-energy tensor describes the density of energy and momentum, and the flux of energy and momentum in a region. Since under the mass-energy equivalence principle we can convert mass units to energy units and vice-versa, this means that the stress-energy tensor describes all the mass and energy in a given region of spacetime.

Put even more simply, the stress-energy tensor represents everything that gravitates.

The stress-energy tensor, being a tensor of rank two in four-dimensional spacetime, has sixteen components that can be written as a 4 × 4 matrix.

Here the components have been color-coded to help clarify their physical interpretations.

- energy density, which is equivalent to mass-energy density; this component includes the mass contribution

,

,  ,

,

- the components of momentum density

,

,  ,

,

- the components of energy flux

The space-space components of the stress-energy tensor are simply the stress tensor from classic mechanics. Those components can be interpreted as:

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

- the components of shear stress, or stress applied tangential to the region

,

,  ,

,

- the components of normal stress, or stress applied perpendicular to the region; normal stress is another term for pressure.

Pay particular attention to the first column of the above matrix: the components  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  , are interpreted as densities. A density is what you get when you measure the flux of 4-momentum across a 3-surface of constant time. Put another way, the instantaneous value of 4-momentum flux is density.

, are interpreted as densities. A density is what you get when you measure the flux of 4-momentum across a 3-surface of constant time. Put another way, the instantaneous value of 4-momentum flux is density.

Similarly, the diagonal space components of the stress-energy tensor —  ,

,  and

and  — represent normal stress, or pressure. Not some weird, relativistic pressure, but plain old ordinary pressure, like what keeps a balloon inflated. Pressure also contributes to gravitation, which raises a very interesting observation.

— represent normal stress, or pressure. Not some weird, relativistic pressure, but plain old ordinary pressure, like what keeps a balloon inflated. Pressure also contributes to gravitation, which raises a very interesting observation.

Imagine a box of air, a rigid box that won't flex. Let's say that the pressure of the air inside the box is the same as the pressure of the air outside the box. If we heat the box — assuming of course that the box is airtight — then the temperature of the gas inside will rise. In turn, as predicted by the ideal gas law, the pressure within the box will increase.

The box is now heavier than it was.

More precisely, increasing the pressure inside the box raised the value of the pressure contribution to the stress-energy tensor, which will increase the curvature of spacetime around the box. What's more, merely increasing the temperature alone caused spacetime around the box to curve more, because the kinetic energy of the gas molecules inside the box also contributes to the stress-energy tensor, via the time-time component  . All of these things contribute to the curvature of spacetime around the box, and thus to the gravitational field created by the box.

. All of these things contribute to the curvature of spacetime around the box, and thus to the gravitational field created by the box.

Of course, in practice, the contributions of increased pressure and kinetic energy would be miniscule compared to the mass contribution, so it would be extremely difficult to measure the gravitational effect of heating the box. But on larger scales, such as the sun, pressure and temperature contribute significantly to the gravitational field.

In this way, we can see that the stress-energy tensor neatly quantifies all static and dynamic properties of a region of spacetime, from mass to momentum to electric charge to temperature to pressure to shear stress. Thus, the stress-energy tensor is all we need on the right-hand side of the equation in order to relate matter, energy and, well, stuff to curvature, and thus to the gravitational field.

Example 1: Stress-energy tensor for a vacuum

The simplest possible stress-energy tensor is, of course, one in which all the values are zero.

This tensor represents a region of space in which there is no matter, energy or fields, not just at a given instant, but over the entire period of time in which we're interested in the region. Nothing exists in this region, and nothing happens in this region.

So one might assume that in a region where the stress-energy tensor is zero, the gravitational field must also necessarily be zero. There's nothing there to gravitate, so it follows naturally that there can be no gravitation.

In fact, it's not that simple. We'll discuss this in greater detail in the next section, but even a cursory qualitative examination can tell us there's more going on than that. Consider the gravitational field of an isolated body. A test particle placed somewhere near but outside of the body will move in a geodesic in spacetime, freely falling inward toward the central mass. A test particle with some constant linear velocity component perpendicular to the interval between the particle and the mass will move in a conic section. This is true even though the stress-energy tensor in that region is exactly zero. This much is obvious from our intuitive understanding of gravity: gravity affects things at a distance. But exactly how and why this happens, in the model of the Einstein field equations, is an interesting question which will be explored in the next section.

Example 2: Stress-energy tensor for an ideal dust

Imagine a time-dependent distribution of identical, massive, non-interacting, electrically neutral particles. In general relativity, such a distribution is called a dust. Let's break down what this means.

- time-dependent

- The distribution of particles in our dust is not a constant; that is to say, the particles may be motion. The overall configuration you see when you look at the dust depends on the time at which you look at it, so the dust is said to be time-dependent.

- identical

- The particles that make up our dust are all exactly the same; they don't differ from each other in any way.

- massive

- Each particle in our dust has some rest mass. Because the particles are all identical, their rest masses must also be identical. We'll call the rest mass of an individual particle

.

.

- non-interacting

- The particles don't interact with each other in any way: they don't collide, and they don't attract or repel each other. This is, of course, an idealization; since the particles are said to have mass

, they must at least interact with each other gravitationally, if not in other ways. But we're constructing our model in such a way that gravitational effects between the individual particles are so small as to be be negligible. Either the individual particles are very tiny, or the average distance between them is very large. This same assumption neatly cancels out any other possible interactions, as long as we assume that the particles are far enough apart.

, they must at least interact with each other gravitationally, if not in other ways. But we're constructing our model in such a way that gravitational effects between the individual particles are so small as to be be negligible. Either the individual particles are very tiny, or the average distance between them is very large. This same assumption neatly cancels out any other possible interactions, as long as we assume that the particles are far enough apart.

- electrically neutral

- In addition to the obvious electrostatic effect of two charged particles either attracting or repelling each other — thus violating our "non-interacting" assumption — allowing the particles to be both charged and in motion would introduce electrodynamic effects that would have to be factored into the stress-energy tensor. We would greatly prefer to ignore these effects for the sake of simplicity, so by definition, the particles in our dust are all electrically neutral.

The easiest way to visualize an ideal dust is to imagine, well, dust. Dust particles sometimes catch the light of the sun and can be seen if you look closely enough. Each particle is moving in apparent ignorance of the rest, its velocity at any given moment dependent only on the motion of the air around it. If we take away the air, each particle of dust will continue moving in a straight line at a constant velocity, whatever its velocity happened to be at the time. This is a good visualization of an ideal dust.

We're now going to zoom out slightly from our model, such that we lose sight of the individual particles that make up our dust and can consider instead the dust as a whole. We can fully describe our dust at any event  — where event is defined as a point in space at an instant in time — by measuring the density

— where event is defined as a point in space at an instant in time — by measuring the density  and the 4-velocity

and the 4-velocity  at

at  . If we have those two pieces of information about the dust at every point within it at every moment in time, then there's literally nothing else to say about the dust: it's been fully described.

. If we have those two pieces of information about the dust at every point within it at every moment in time, then there's literally nothing else to say about the dust: it's been fully described.

Density

Let's start by figuring out the density of dust at a the event  , as measured from the perspective of an observer moving along with the flow of dust at

, as measured from the perspective of an observer moving along with the flow of dust at  . The density

. The density  is calculated very simply:

is calculated very simply:

where  is the mass of each particle and

is the mass of each particle and  is the number of particles in a cubical volume one unit of length on a side centered on

is the number of particles in a cubical volume one unit of length on a side centered on  . This quantity is called proper density, meaning the density of the dust as measured within the dust's own reference frame. In other words, if we could somehow imagine the dust to measure its own density, the proper density is the number it would get.

. This quantity is called proper density, meaning the density of the dust as measured within the dust's own reference frame. In other words, if we could somehow imagine the dust to measure its own density, the proper density is the number it would get.

Clearly proper density is a function of position, since it varies from point to point within the dust; the dust might be more "crowded" over here, less "crowded" over there. But it's also a function of time, because the configuration of the dust itself is time-dependent. If you measure the proper density at some point in space at one instant of time, then measure it at the same point in space at a different instant of time, you may get a different measurement. By convention, when dealing with a quantity that depends both on position in space and on time, physicists simply say that the quantity is a function of position, with the understanding that they're referring to a "position" in four-dimensional spacetime.

4-velocity

The other quantity we need is 4-velocity. Four-velocity is an extension of three-dimensional velocity (or 3-velocity). In three dimensional space, 3-velocity is a vector with three components. Likewise, in four-dimensional spacetime, 4-velocity is a vector with four components.

Directly measuring 4-velocity is an inherently tricky business, since one of its components describes motion along a "direction" that we cannot see with our eyes: motion through time. The math of special relativity lets us calculate the 4-velocity of a moving particle given only its 3-velocity  (with components

(with components  where

where  ) and the speed of light. The time component of 4-velocity is given by:

) and the speed of light. The time component of 4-velocity is given by:

and the space components  ,

,  and

and  by:

by:

where  is the boost, or Lorentz factor:

is the boost, or Lorentz factor:

and where  , in turn, is the square of the Euclidean magnitude of the 3-velocity vector

, in turn, is the square of the Euclidean magnitude of the 3-velocity vector  :

:

Therefore, if we know the 3-velocity of the dust at event  , then we can calculate its 4-velocity. (For more details on the how and why of 4-velocity, refer to the article on special relativity.)

, then we can calculate its 4-velocity. (For more details on the how and why of 4-velocity, refer to the article on special relativity.)

Just as proper density is a function of position in spacetime, 4-velocity also depends on position. The 4-velocity of our dust at a given point in space won't necessarily be the same as the 4-velocity of the dust at another point in space. Likewise, the 4-velocity at a given point at a given time may not be the same as the 4-velocity of the dust at the same point at a different time. It helps to think of 4-velocity as the velocity of the dust through a point in both space and time.

Assembling the stress-energy tensor

Since the density and the 4-velocity fully describe our dust, we have everything we need to calculate the stress-energy tensor.

where the symbol  indicates a tensor product. The tensor product of two vectors is a tensor of rank two, so the stress-energy tensor must be a tensor of rank two. In an arbitrary coordinate frame

indicates a tensor product. The tensor product of two vectors is a tensor of rank two, so the stress-energy tensor must be a tensor of rank two. In an arbitrary coordinate frame  , the contravariant components of the stress-energy tensor for an ideal dust are given by:

, the contravariant components of the stress-energy tensor for an ideal dust are given by:

From this equation, we can now calculate the contravariant components of the stress-energy tensor for an ideal dust.

Time-time component

We start with the contravariant time-time component  :

:

If we rearrange the terms in this equation slightly, something important becomes apparent:

Recall that  is a density quantity, in mass per unit volume. By the mass-energy equivalence principle, we know that

is a density quantity, in mass per unit volume. By the mass-energy equivalence principle, we know that  . So we can interpret this component of the stress-energy tensor, which is written here in terms of mass-energy, to be equivalent to an energy density.[3]

. So we can interpret this component of the stress-energy tensor, which is written here in terms of mass-energy, to be equivalent to an energy density.[3]

Off-diagonal components

The off-diagonal components of the tensor —  where

where  and

and  are not equal — are calculated this way:

are not equal — are calculated this way:

Again, recall that  is a quantity of mass per unit volume. Multiplying a mass times a velocity gives momentum, so we can interpret

is a quantity of mass per unit volume. Multiplying a mass times a velocity gives momentum, so we can interpret  as the density of momentum along the

as the density of momentum along the  direction, multiplied by constants

direction, multiplied by constants  and

and  . Momentum density is an extremely difficult quantity to visualize, but it's a quantity that comes up over and over in general relativity. If nothing else, one can take comfort in the fact that momentum density is mathematically equivalent to the product of mass density and velocity, both of which are much more intuitive quantities.

. Momentum density is an extremely difficult quantity to visualize, but it's a quantity that comes up over and over in general relativity. If nothing else, one can take comfort in the fact that momentum density is mathematically equivalent to the product of mass density and velocity, both of which are much more intuitive quantities.

Note that the off-diagonal components of the tensor are equal to each other:

In other words, in the case of an ideal dust, the stress-energy tensor is said to be symmetric. A rank two symmetric tensor is said to be symmetric if  .

.

Diagonal space components

The diagonal space components of the stress-energy tensor are calculated this way:

In this case, we're multiplying a four-dimensional mass density,  , by the square of a component of 4-velocity. By dimensional analysis, we can see:

, by the square of a component of 4-velocity. By dimensional analysis, we can see:

Recall that the force has units:

If we divide the units of the diagonal space component by the units of force, we get:

So the diagonal space components of the stress-energy tensor come are expressed in terms of force per unit volume. Force per unit area are, of course, the traditional units of pressure in three-dimensional mechanics. So we can interpret the diagonal space components of the stress-energy tensor as the components of "4-pressure"[4] in spacetime.

The big picture

We now know everything we know to assemble the entire stress-energy tensor, all sixteen components, and look at it as a whole.[5]

The large-scale structure of the tensor now becomes apparent. This is the stress-energy tensor of an ideal dust. The tensor is composed entirely out of the proper density and the components of 4-velocity. When velocities are low, the coefficient  , even though it's a squared value, remains extremely close to one.

, even though it's a squared value, remains extremely close to one.

The time-time component includes a mass multiplied by the square of the speed of light, so it has to do with energy. The rest of the top row and left column all include the speed of light as a coefficient, as well as density and velocity; in the case of an ideal dust which is made up of non-interacting particles, the energy flux along any basis direction is the same as the momentum density along that direction. This is not the case in other, less simple models, but it's true here.

The diagonal space components of the tensor represent pressure. For example, the  component represents the pressure that would be exerted on a plane perpendicular to the

component represents the pressure that would be exerted on a plane perpendicular to the  direction.

direction.

The off-diagonal space components represent shear stress. The  component, for instance, represents the pressure that would be exerted in the

component, for instance, represents the pressure that would be exerted in the  direction on a plane perpendicular to the

direction on a plane perpendicular to the  axis.

axis.

The overall process for calculating the stress-energy tensor for any system is fairly similar to the example given here. It involves taking into account all the matter and energy in the system, describing how the system evolves over time, and breaking that evolution down into components which represent individual densities and fluxes along different directions relative to a chosen coordinate basis.

As can easily be imagined, the task of constructing a stress-energy tensor for a system of arbitrary complexity can be a very daunting one. Fortunately, gravity is an extremely weak interaction, as interactions go, so on the scales where gravity is interesting, much of the complexity of a system can be approximated. For instance, there is absolutely nothing in the entire universe that behaves exactly like the ideal dust described here; every massive particle interacts, in one way or another, with other massive particles. No matter what, a real system is going to be very much more complex than this approximation. Yet, the ideal dust solution remains a much-used approximation in theoretical physics specifically because gravity is such a weak interaction. On the scales where gravity is worth studying, many distributions of matter, including interstellar nebulae, clusters of galaxies, even the whole universe really do behave very much like an ideal dust.

The left side of the equation: the Einstein curvature tensor

We will recall that the Einstein field equations can be written as a single tensor equation:

The right side of the equation consists of some constants and the stress-energy tensor, described in significant detail in the previous section. The right side of the equation is the "matter" side. All matter and energy in a region of space is described by the right side of the equation.

The left side of the equation, then, is the "space" side. Matter tells space how to curve, and space tells matter how to move. So the left side of the Einstein field equation must necessarily describe the curvature of spacetime in the presence of matter and energy.

Some assumptions about the universe

Before we proceed into a discussion of what curvature is and how the Einstein equation describes it, we must first pause to state some fundamental assumptions about the universe.[6]

The first assumption we're going to make is that spacetime is continuous. In essence, this means that for any event  in spacetime — that is, any point in space and moment in time — there exists some local neighborhood of

in spacetime — that is, any point in space and moment in time — there exists some local neighborhood of  where the intrinsic properties of spacetime differ from those at

where the intrinsic properties of spacetime differ from those at  by only an infinitesimal amount.

by only an infinitesimal amount.

The second assumption we're going to make is that spacetime is differentiable everywhere. In other words, the geometry of spacetime doesn't have any sharp creases in it.

If we hold these two assumptions to be true, then a convenient property of spacetime emerges: Given any event  , there exists a local neighborhood where spacetime can be treated as flat, that is, having zero curvature. It is not necessarily true that all of spacetime be flat — in fact, it most definitely is not — but given any event in spacetime, there exists some neighborhood around it that is flat. This neighborhood may be arbitrarily small in both time and space, but it is guaranteed to exist as long as our two assumptions remain valid.

, there exists a local neighborhood where spacetime can be treated as flat, that is, having zero curvature. It is not necessarily true that all of spacetime be flat — in fact, it most definitely is not — but given any event in spacetime, there exists some neighborhood around it that is flat. This neighborhood may be arbitrarily small in both time and space, but it is guaranteed to exist as long as our two assumptions remain valid.

With these two assumptions and this convenient property in hand, we will now examine what it means to say that spacetime is curved.

Flatness versus curvature

Let's start by considering the simplest possible geometry[7]: the Euclidean plane.

The Euclidean plane is an infinite, flat, two-dimensional surface. A sheet of paper is a good approximation of the Euclidean plane. Onto this plane, we can project a set of Cartesian coordinates. By "Cartesian," we mean that the coordinate axes are straight lines, that they are perpendicular, and that the unit lengths of the axes are equal. A fancier term for a Cartesian coordinate system is an orthonormal basis.

Note carefully the distinction between the Euclidean plane and Cartesian coordinates. The plane exists as a thing in and of itself, just as a blank piece of paper does. It has certain properties, which we'll get into below. Those properties are intrinsic to the plane. That is, the properties don't have anything to do with the coordinates we project onto the plane. The plane is a geometric object, and the coordinates are the method by which we measure the plane. (The emphasis on the word measure there is not accidental; please keep this idea in the foreground of your mind as we continue.)

Cartesian coordinates are not the only coordinates we can use in the Euclidean plane. For example, instead of having axes that are perpendicular to each other, we could choose axes that are straight lines, but that meet at some non-perpendicular angle. These types of coordinates are called oblique.

For that matter, we're not bound to use straight-line coordinates at all. We could instead choose polar coordinates, wherein every point on the plane is described by a distance from a fixed but arbitrary point and an angle from a fixed but arbitrary direction. Polar coordinates are often more convenient than Cartesian coordinates. For example, when navigating a ship on the ocean, the location of a fixed point is usually described in terms of a bearing and a distance, where the distance is the straight-line distance from the ship to the point, and the bearing is the clockwise angle relative to the direction in which the ship is sailing. Polar coordinates in two and three dimensions are often used in physics for similar reasons.

But there's a fundamental problem with polar coordinates that is not present with Cartesian coordinates. In Cartesian coordinates, every point on the Euclidean plane is identified by exactly one set of real numbers: there is precisely one set of  and

and  coordinates for every point, and every point corresponds to precisely one set of coordinates.

coordinates for every point, and every point corresponds to precisely one set of coordinates.

This is not true in polar coordinates. What are the unique polar coordinates for the origin? The radial distance is obviously zero, but what is the angle? In actuality, if the radial distance is zero, any angle can be used, and the coordinates will identify the same point. The one-to-one correspondence between points in the plane and pairs of coordinates breaks down at the origin.

In mathematical terms, polar coordinates in the Euclidean plane have a coordinate singularity at the origin. A coordinate singularity is a point in space where ambiguities are introduced, not because of some intrinsic property of space, but because of the coordinate basis you chose.

So clearly there may exist a reason to choose one coordinate system over another when measuring — there's that word again — the Euclidean plane. Polar coordinates have a singularity at the origin — in this case, a point of undefined angle — while Cartesian coordinates have no such singularities anywhere. So there may be good reason to choose Cartesian coordinates over polar coordinates when measuring the Euclidean plane.

Fortunately, this is always possible. The Euclidean plane can always be measured by Cartesian coordinates; that is, coordinates wherein the axes are straight and perpendicular at their intersection, and where lines of constant coordinate — picture the grid on a sheet of graph paper — are always a constant distance apart no matter where you measure them.

Imagine taking a piece of graph paper, which is printed in a pattern that lets us easily visualize the Cartesian coordinate system, and rolling it into a cylinder. Do any creases appear in the paper? No, it remains smooth all over. Do the lines printed on the paper remain a constant distance apart everywhere? Yes, they do. In technical mathematical terms, then, the surface of a cylinder is flat. That is, it can be measured by an orthonormal basis, and there is everywhere a one-to-one correspondence between sets of coordinates and points on the surface. It's possible not to use an orthonormal basis to measure the surface; one might reasonably choose polar coordinates, or some other arbitrary coordinate system, if it's more convenient. But whichever basis is actually used, it's always possible to switch to an orthonormal basis instead.

Now imagine wrapping a sheet of graph paper around a basketball. Does the paper remain smooth? No, if we press it down, creases appear. Do the lines on the paper remain parallel? No, they have to bend in order to conform the paper to the shape of the ball. In the same technical mathematical terms, the surface of a sphere is not flat. It's curved. That is, it is not possible to measure the surface all over using an orthonormal basis.

But what if we focus our attention only on a part of the sphere? What if instead of measuring a basketball, we want to measure the whole Earth? The Earth is a sphere, and therefore its surface is curved and can't be measured all over with Cartesian coordinates. But if we look only at a small section of the surface — a square mile on a side, for instance — then we can project a set of Cartesian coordinates that work just fine. If we choose our region of interest to be sufficiently small, then Cartesian coordinates will fit on the surface to within the limits of our ability to measure the difference.

The surface of a sphere, then, is globally curved, but locally flat. In physicist jargon, the surface of a sphere can be flattened over a sufficiently small region. Not the whole sphere all at once, nor half of it, nor a quarter of it. But a sufficiently small region can be dealt with as if it were a Euclidean plane.

But this brings up an important point. The entire surface of the sphere is curved, and thus can't be approximated with Cartesian coordinates. But a sufficiently small patch of the surface can be approximated with Cartesian coordinates. This implies, then, that "curvedness" isn't an either-or property. Somewhere between the locally flat region of the surface and the entire surface, the amount of curvature goes from none to some value. Curvature, then, must be something we can measure.

The metric tensor

It is a fundamental property of the Euclidean plane that, when Cartesian coordinates are used, the distance  between any two points

between any two points  and

and  is given by the following equation:

is given by the following equation:

where  and

and  are the distance between

are the distance between  and

and  in the

in the  and

and  directions, respectively. This is essentially a restatement of the universally known Pythagorean theorem, and in the context of general relativity, it is called the metric equation. Metric, of course, comes from the same linguistic root as the word measure, and since this is the equation we use to measure distances, it makes sense to call it the metric equation.

directions, respectively. This is essentially a restatement of the universally known Pythagorean theorem, and in the context of general relativity, it is called the metric equation. Metric, of course, comes from the same linguistic root as the word measure, and since this is the equation we use to measure distances, it makes sense to call it the metric equation.

But this particular metric equation only works on the Euclidean plane with Cartesian coordinates. If we use polar coordinates, this equation won't work.[8] If we're on a curved surface instead of a plane, this equation won't work. This metric equation is only valid on a flat surface with Cartesian coordinates.

Which makes it pretty useless, since so much of physics revolves around curved spacetime and spherical coordinates.

What we need is a generalized metric equation, some way of measuring the interval of any two points regardless of what coordinate system we're using or whether our local geometry is flat or curved.

The metric tensor equation provides this generalization.

If  is any vector having components

is any vector having components  , the length of

, the length of  is given by the following equation:

is given by the following equation:

where  is the metric tensor, and

is the metric tensor, and  and

and  range over the number of dimensions. Recall that Einstein summation notation means that this is actually a sum over indices

range over the number of dimensions. Recall that Einstein summation notation means that this is actually a sum over indices  and

and  . If we assume that we're in the two-dimensional Euclidean plane, the metric tensor equation expands to:

. If we assume that we're in the two-dimensional Euclidean plane, the metric tensor equation expands to:

The terms of the metric tensor, then, must be numerical coefficients in the metric equation. We already know what these equations need to be to make the metric equation work in the Euclidean plane with Cartesian coordinates:

Now we can write the metric tensor for the Euclidean plane in Cartesian coordinates in the form of a 2 × 2 matrix:

So in the case of the Euclidean plane with Cartesian coordinates, the metric tensor is the Kronecker delta:

Of course, the same concepts apply if we expand our interest from the plane to three-dimensional Euclidean space with Cartesian coordinates. We just have to let the indices of the Kronecker delta run from 1 to 3.

Which gives us the following metric equation for the length of a vector  (omitting terms with zero coefficient):

(omitting terms with zero coefficient):

Which precisely agrees with the Pythagorean theorem in three dimensions. So given a metric tensor  for any space and coordinate basis, we can calculate the distance between any two points. The metric tensor, therefore, is what allows us to measure curved space. In a very real sense, the metric tensor describes the shape of both the underlying geometry and the chosen coordinate basis.

for any space and coordinate basis, we can calculate the distance between any two points. The metric tensor, therefore, is what allows us to measure curved space. In a very real sense, the metric tensor describes the shape of both the underlying geometry and the chosen coordinate basis.

But relativity is concerned not with geometrically abstract space; we're interested in very real spacetime, and that requires a slightly different kind of metric.

The local Minkowski metric

Geodesics

Parallel transport and intrinsic curvature

The Riemann and Ricci tensors and the curvature scalar

The Einstein tensor

The cosmological constant

Exact Solutions in General Relativity

Tests of General Relativity

General relativity provides one explanation for the precession of Mercury's perihelion, which was moving at a different speed than that predicted by a simple application of Newton's law of universal gravitation. (Previous scientists had attempted to explain it by the gravitational pull of a hypothetical planet inside Mercury's orbit, which they called Vulcan. This could also be explained by altering the precise inverse-square relation of Newtonian gravity to distance, but that was disfavored by mathematicians due to its inelegance in integrating.)

British historian Paul Johnson declares the turning point in the acceptance of general relativity to have been when Sir Arthur Eddington, an esteemed English astronomer, ventured out on a boat off Africa in 1919 with a local Army unit to observe the bending of starlight around the sun during a total solar eclipse. General relativity predicted that the light from the stars would be bent due to passing close to the sun. (A smaller degree of bending could also be consistent with Newton's theory, if one hypothesized light to consist of particles. However, that particle theory of light had gone out of favor previously.) Eddington detected a bending of light, but his range of error overlapped both Einstein's and Newton's predictions. Upon his return to England, Eddington declared that his observations proven the theory of relativity. His experiment was later confirmed by more rigorous experiments, such as those performed by the Hubble Space Telescope [9][10][11]. Lorentz has this to say on the discrepancies between the empirical eclipse data and Einstein's predictions.

- It indeed seems that the discrepancies may be ascribed to faults in observations, which supposition is supported by the fact that the observations at Prince's Island, which, it is true, did not turn out quite as well as those mentioned above, gave the result, of 1.64, somewhat lower than Einstein's figure.[12]

Relation to Special Relativity

Special relativity is the limiting case of general relativity where all gravitational fields are weak. Alternatively, special relativity is the limiting case of general relativity when all reference frames are inertial (non-accelerating and without gravity).

External Links

- Einstein, Albert (1916), "The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity" (PDF), Annalen der Physik 49

References

- ↑ Misner, Thorne & Wheeler. Gravitation. (1973)

- ↑ The words "flat" and "curved" used in this article are the same terms used by differential topology experts.

- ↑ Actually rewriting the equation for the time-time component in terms of energy density requires refining our proper density equation into a form that doesn't depend on counting particles in a unit volume. Such a refinement is beyond the scope of this discussion. In less abstract dust solutions, the mass density is usually either assumed to be constant over space (as in the FLRW solution that models a homogenous, isotropic expanding or contracting universe) or is assumed to depend only on the radius of the distribution (as in the LTB solution that models gravitational collapse). At this point, it is sufficient merely to understand that matter density and energy density, and matter flux and energy flux, are equivalent concepts under general relativity.

- ↑ Not a standard term.

- ↑ The stress-energy tensor is practically never written out in matrix form this way, even in textbooks. This is purely for illustration.

- ↑ As we will later see, these assumptions may in fact turn out not to be valid for all of spacetime. It may be more accurate, although significantly less satisfying, to say that we assume these things to be true about spacetime, except where they aren't.

- ↑ Well, the simplest possible interesting geometry, anyway.

- ↑ This is trivial to demonstrate. If

is zero and

is zero and  is non-zero, then

is non-zero, then  will be non-zero for a vector that obviously has no length.

will be non-zero for a vector that obviously has no length.

- ↑ Hubble Gravitational Lens Photo

- ↑ Gravitational Lensing

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Lorentz, H.A. The Einstein Theory of Relativity