Difference between revisions of "Hieroglyphs"

DavidB4-bot (Talk | contribs) (clean up & uniformity) |

DavidB4-bot (Talk | contribs) m (→Decline, Loss and Rediscovery: HTTP --> HTTPS [#1], replaced: http://www.flickr.com → https://www.flickr.com) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

[[Image:Hieroglyphs.jpg|thumb|right|Egyptian hieroglyphs on a Late Period [[sarcophagus]] at the [[British Museum]] in [[London]].]] | [[Image:Hieroglyphs.jpg|thumb|right|Egyptian hieroglyphs on a Late Period [[sarcophagus]] at the [[British Museum]] in [[London]].]] | ||

'''Hieroglyphs''' were developed in [[Ancient Egypt]] as a way to write the [[Egyptian language]]. Other cultures, most notably the [[Maya]] civilization also used similar writing systems, though Maya hieroglyphs were an entirely independent development, taking place several thousand years later, and were much more restricted in use. Whilst Egyptian hieroglyphs were first deciphered in the 19th century by [[Jean Francois Champollion]], Mayan hieroglyphs have only recently begun to be understood, and much work remains to be done. | '''Hieroglyphs''' were developed in [[Ancient Egypt]] as a way to write the [[Egyptian language]]. Other cultures, most notably the [[Maya]] civilization also used similar writing systems, though Maya hieroglyphs were an entirely independent development, taking place several thousand years later, and were much more restricted in use. Whilst Egyptian hieroglyphs were first deciphered in the 19th century by [[Jean Francois Champollion]], Mayan hieroglyphs have only recently begun to be understood, and much work remains to be done. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 18: | ||

=== Decline, Loss and Rediscovery === | === Decline, Loss and Rediscovery === | ||

| − | The Roman era sees the decline of the hieroglyphic system of writing. The last surviving knowledgeable and literate hieroglyphic inscription in ancient times dates from August 24, 396 AD and was inscribed in the temple complex of Philae, five years after Theodosius I forced the closure of all non-Christian places of worship in Roman territory. The inscription, the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom is catalogued as Philae 436 ([ | + | The Roman era sees the decline of the hieroglyphic system of writing. The last surviving knowledgeable and literate hieroglyphic inscription in ancient times dates from August 24, 396 AD and was inscribed in the temple complex of Philae, five years after Theodosius I forced the closure of all non-Christian places of worship in Roman territory. The inscription, the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom is catalogued as Philae 436 ([https://www.flickr.com/photos/mkubecka/2093092240/ picture]). |

Even before this some Greco-Roman writers had written elaborate and wholly inaccurate works on the “mystical” or “symbolic” interpretations of the signs, and such works continued into the Islamic era. These works inadvertently frustrated attempts at translation into the modern era. | Even before this some Greco-Roman writers had written elaborate and wholly inaccurate works on the “mystical” or “symbolic” interpretations of the signs, and such works continued into the Islamic era. These works inadvertently frustrated attempts at translation into the modern era. | ||

| Line 98: | Line 97: | ||

* '''Yousef, A A H (2003)''', ''From Pharaoh's Lips: Ancient Egyptian Language in the Arabic of Today'', AUC Press, Cairo | * '''Yousef, A A H (2003)''', ''From Pharaoh's Lips: Ancient Egyptian Language in the Arabic of Today'', AUC Press, Cairo | ||

| − | [[Category:Writing | + | [[Category:Writing Systems]] |

[[Category:Ancient History]] | [[Category:Ancient History]] | ||

[[Category:Ancient Egypt]] | [[Category:Ancient Egypt]] | ||

Revision as of 17:26, September 26, 2018

Hieroglyphs were developed in Ancient Egypt as a way to write the Egyptian language. Other cultures, most notably the Maya civilization also used similar writing systems, though Maya hieroglyphs were an entirely independent development, taking place several thousand years later, and were much more restricted in use. Whilst Egyptian hieroglyphs were first deciphered in the 19th century by Jean Francois Champollion, Mayan hieroglyphs have only recently begun to be understood, and much work remains to be done.

Note: This article only deals with Egyptian Hieroglpyhs.

Contents

Basic Concepts

Contrary to popular belief, Egyptian hieroglyphs are not generally pictograms or logograms. Like the Latin and Greek alphabets, hieroglyphs are primarily phonograms. Unlike these alphabets however, one sign can convey up to three consonants, whilst some words also feature an additional silent sign at the end (a determinative) that helps convey the meaning of the word, and avoid confusion between words that would otherwise be spelt with exactly the same signs. This is especially important as, like in modern Arabic and Hebrew alphabets, vowels are not included in the text. Only consonants are recorded.

Development

Pre and Early Dynastic

Classical (Middle) Egyptian

Ptolemaic Era and Cryptographic Inscriptions

During the Ptolemaic era the number of signs was increased dramatically, from around 800 to several thousand, many of which were ligatures of existing signs. The rise in the complexity coincided with the rise of so-called cryptographic texts in temple inscriptions that aimed to deliberately obscure and challenge the reader. The reasons for this are unknown, and various reasons from xenophobia, cultural pride and nationalism (see also: Great Egyptian Revolt) to marginalization and isolation of traditional religion and the rise of Hellenic and syncretic cults have all been suggested.

Decline, Loss and Rediscovery

The Roman era sees the decline of the hieroglyphic system of writing. The last surviving knowledgeable and literate hieroglyphic inscription in ancient times dates from August 24, 396 AD and was inscribed in the temple complex of Philae, five years after Theodosius I forced the closure of all non-Christian places of worship in Roman territory. The inscription, the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom is catalogued as Philae 436 (picture).

Even before this some Greco-Roman writers had written elaborate and wholly inaccurate works on the “mystical” or “symbolic” interpretations of the signs, and such works continued into the Islamic era. These works inadvertently frustrated attempts at translation into the modern era.

The French invasion of Egypt in 1798 focused European scholarly and academic attention on Egypt for the first time. The discovery of the Rosetta Stonein 1799 was recognized immediately as the “key” to correct interpretation of Egyptian hieroglyphs, having the same text recorded in Greek and in hieroglyphs, as well as another unknown script.

The British captured the stone in 1801 amid events that are still unclear and controversial. However, the French scholars had taken casts of the stone, with which they returned to Paris. The British believed a method of mathematical deduction would eventually allow the text to be translated, given sufficient time. However, John Francois Champollion, a brilliant linguist familiar with 24 languages, realized both that hieroglyphs had to be phonogrammatic in nature, and also that translating the language was as important as the alphabet.

Champollion was familiar with the Coptic language, and he correctly realized that this was the final evolution of the Egyptian language written in hieroglyphs. By applying his knowledge of Coptic, and the works of the Thomas Young, his British counterpart, Champollion successfully transliterated the first hieroglyphs and translated the first Egyptian words in 1822. His work, however, was constantly thwarted by the religious-political situation in France during the reign of Charles X. In return for part-funding mission to Egypt by the state to test his theories, he was forbidden to publish anything contravening the Biblical account of history. As such, many of his dairies, containing details of monuments and tombs pre-dating the supposed date of the “Great Flood” were only published after his death.

Despite this, his mission was successful. However, in recent times his reputation has been damaged due to the looting of artefacts undertaken during the mission, including cutting of scenes from tomb walls, even Royal tombs. It should be noted that this was standard practice at the time, and Champollion was expected to return with treasures as a "return" on the "investment" the state made in his mission.

Relationship with Hieratic, Demotic and Coptic

Hieratic is a cursive form of the hieroglyphic writing system (though different to cursive hieroglyphs) that was suited to working with a reed brush/pen. Hieratic does not replace hieroglyphs, but rather complements them, with hieroglyphs serving mostly in monumental inscriptions in stone and ritual use, and hieratic for administrative and lesser religious documents. It is attested from the end of the Early Dynastic period onwards and is written in ink primarily on papyrus and ostraca. Over time increasingly cursive forms of hieratic appear, eventually formalising as Demotic. Originally intended for administrative purposes, Hieratic was used mainly for religious papyri following the development of Demotic. Use of Hieratic declined along with Egyptian religion, and ceased to be used during the Roman era.

During the 26th Dynasty, an additional cursive writing system appears, Demotic. Essentially a more cursive form of Hieratic, demotic makes extensive use of ligatures. Demotic also differs from Hieratic in that it was occasionally also deployed as a monumental script, though it does not replace hieroglyphs, and Demotic is only rarely employed monumentally. Demotic began to replaced by the Greek and Coptic writing systems in the third century AD. The last known Demotic inscription was from Philae in 452AD, just 56 years after the last known literate use of hieroglyphs.

The Coptic script is entirely different to the other three written forms of Egyptian. For the most part it is not related to hieroglyphs, but to the Greek alphabet, except for the six “additional” letters which reproduce sounds not used in Greek, which are taken from Demotic, and thus hieroglyphs. Coptic also records vowels as well as consonants, but does not use determinatives or any equivalent. Coptic script first appears third century AD, and is still used in the Coptic church. The language it represents is a late form of Egyptian many Greek loan words included.

Sign Usage

The number of Hieroglyphic signs is much larger than in the Latin or Greek alphabets. This is due to the number of different uses signs can have, to represent a single, two or three consonants (monoliteral, biliteral and triliteral signs), and as a non-sounded determinative. In total, the classical Egyptian sign set features approximately 800 signs. In the Ptolemaic era, thousands of new signs were added, which are not included in most dictionaries and classifications of the written script, many of which were effectively ligatures of existing signs.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions are always read “into the face” of the signs, which can either be left to right or right to left, depending on the inscription. Text may be arranged in columns or in lines. Text and art are inseparable in Egyptian writing, and so the layout of text is (except in administrative documents) dictated by aesthetics.

Monoliteral Signs

These are the easiest part of the system for most western students to learn. The set of 24 monoliteral signs function in the same way as the Latin or Greek alphabets do, with a single sign representing a single sound. Words are produced by placing the signs in order one after the other. The example below is the cartouche of Khufu:

When tourists in Egypt often have their name spelt in hieroglyphs on jewellery or papyrus, it is commonly done with monoliteral signs. These signs are also used in the first stage of teaching Egyptology students to read Egyptian texts, even if their ultimate aim is to learn one of the other scripts (hieratic or demotic).

Biliteral and Triliteral Signs

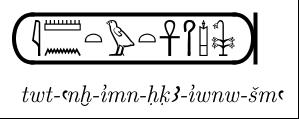

Biliteral and Triliteral signs are single hieroglyphs that convey two or three consonantal sounds, for example the well known ankh sign that conveys the sounds a-n-x (pronounced “Ankh”) and commonly used for the complete Egyptian work “anx” (or “life”), though it may be used in any situation where the a-n-x sound is needed, such as in the name of Tutankhamun, shown below.

Determinatives

Many words in Egyptian are spelt with the addition of one, and occasionally more, determinatives. These are signs added to the end of a word but have no sound value, and are not pronounced. They are used to aid the reader and in clarifying between homophones. The use of distinctive or rare two or three consonant signs, some extremely specialised, also aid in this. As hieroglyphic inscriptions do not include spaces between words, determinatives can also help the reader in separating words. They also serve an important artistic and aesthetic role.

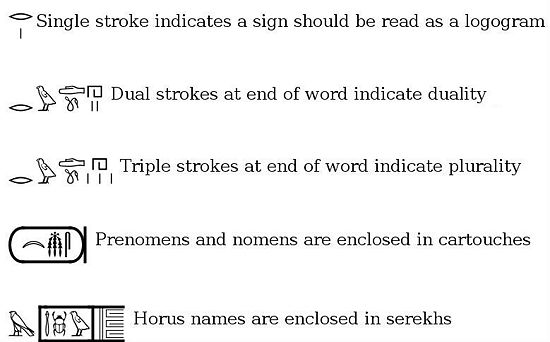

Logogrammatic Usage

Although used only occasionally, it is possible for certain signs to be used to directly represent an object. This is indicated in the text by the addition of a single vertical stroke under the sign to indicate to the reader that the sign should be read in the way, rather than as part of a phonogram.

Grammatical Signs

Strokes and points are additional signs that, like determinatives, are not pronounced They serve to represent the grammar of the text.

Gardiner Classification

Sir Alan Gardiner developed a classification system for hieroglyphs, cataloguing signs by type or what they depict, i.e. birds, man and his occupations etc. Signs that do not depict particular items are classified by shape, i.e. tall, flat etc. Groups are identified by letter, A to Z, and Aa for unclassified signs.

In addition each sign is assigned a code based on its group. A list of signs under the Gardiner classification can be found here.

Transliteration and Electronic Reproduction

The 24 consonantal sounds represented by hieroglyphs can be transliterated into a Latin-based alphabet. This alphabet is available as a font that can be added to a computer system for use in any modern word processing software, as well as in dedicated software for handling hieroglyphs.

This transliteration script is unable to record exactly what signs were used in the original text. Should this be required, it is possible to either refer to the Gardiner assigned codes, or, as is far more common, reproduce the original signs either by hand (as in the Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, one of the few modern hand written publications) or digitally.

Both commercial and open source software is available for producing hieroglyphs on modern computer systems. The most established commercial application is InScribe, used on Windows based PC’s and MacOS systems. In recent years, an open source alternative, JSesh has been adopted, particularly by Egyptology students, and is available for Windows and Linux platforms. WikiHiero is another modern development, aimed at online deployment.

However, prior to the development of such programs and particularly before the deployment of Unicode in operating systems, the transcription font and reproduction of hieroglyphs digitally was restriction to complex and unwieldy deployment of imported images into documents. As such, for effective transcription the Manual de Codage (MdC) system was developed, using a mixture of uppercase and substitute letters to depict the 24 characters of the transcription “alphabet”.

Bibliography

- Allen, J P (2000), Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and culture of Hieroglyphs, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

- Collider, M and Manley, B (1998), How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles

- Gardiner, A H (1957), Egyptian Grammar (3rd. Ed.), Griffith Institute, Oxford

- Shaw, I and Nicholson, P (2008), Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, British Museum Press, London

- Yousef, A A H (2003), From Pharaoh's Lips: Ancient Egyptian Language in the Arabic of Today, AUC Press, Cairo