Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong, (1893-1976) was the leader of Chinese Communism and a ruthless atheist dictator after he came to power in 1949. While not the founder, he was an early member of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. In 1935, Mao was elected to the Executive Committee of the Comintern in Moscow and remained on this committee until it was publicly disbanded in 1943. Mao is regarded as perhaps the biggest mass murderer in history. [1]

Contents

Soviet national liberation movement

Edgar Snow introduced Mao and Zhou Enlai to American readers in 1937 in his book, Red Star Over China, shortly after the Chinese Red Armywas forced out of its base in Jiangxi province by Chiang Kai-shek [pinyin spelling=Jiang Jieshi] in 1934 and their year long retreat to Yunnan known as the Long March. The CCP set off with 100,000 people. Over the next year, they would trek 6000 miles over mountains, swamps and deserts. Somewhere between 4000 and 8000 of the marchers actually reached Yunnan province (Fairbank 305). However, Mao alleged that the Long March served as a "seeding machine" to spread Communist ideas around China. Snow wrote, "The political ideology, tactical line and theoretical leadership of the Chinese Communists have been under the close guidance, if not positive detailed direction, of the Communist International, which during the last decade has become virtually a bureau of the Russian Communist Party." And he further declared that the CCP had to subordinate itself to the "strategic requirements of Soviet Russia, under the leadership of Stalin."[1] However, in early 1935, after a series of disastrous defeats under the leadership of the so-called "28 Bolsheviks" - Chinese communists trained in Moscow - Mao gained the leadership of the CCP. From then on, for better or for worse, he pursued a policy that was more independent of Moscow. (Fairbank 307, 310).

That being said, the Comintern's influence over the CCP is clearly shown in 1936. During the conflict between the CCP and Chiang Kaishek's Guomindang, the Japanese had begun taking over Chinese territory. In 1931 they annexed Manchuria. Between 1931 and 1936 they took over the rest of China's northernmost provinces and were at the gates of Beijing. In 1936, Zhang Xueliang, the former leader of Manchuria, who was frustrated at what he saw as Chiang Kaishek's inaction in the face of the Japanese threat, kidnapped Chiang Kaishek at Xian and turned him over to the Communists. At the instigation of the Comintern, instead of executing their arch-enemy, the Communists won a propaganda victory by making an alliance with him (Fairbank 310). From 1937-1944 the CCP and the Guomindang (GMD) fought together against the Japanese in the "Second United Front". At the end of the war, the USA tried hard to get the CCP and GMD to work together to form a coalition government (Fairbank 330), but the civil war quickly broke out again.

Subversion

Mao's victory over Chiang Kaishek's GMD in the second Civil War (1945-1949) was partly due to CCP tactics, and partly to the failures of the Guomindang. Even Chiang Kaishek himself acknowledged that the Guomindang had become corrupt (Fairbank 291). Although there is no evidence that Chiang himself was corrupt, his supporters took advantage of their positions of power to seize valuable assets during the Japanese surrender. Corruption in the GMD army was so great that the ordinary soldiers were chronically short of food. The GMD also insisted on treating the Chinese who had lived under Japanese occupation as collaborators, which caused resentment. The other mistake the GMD made was to focus on occupying the major cities, ignoring the countryside in between them. The CCP exploited the GMD's mistakes by making alliances with other groups that were unhappy with the GMD and by fighting a guerrilla campaign in the countryside. The GMD soon found themselves divided and isolated in the major cities, which the CCP picked off one by one. Towards the end of the war, whole companies of GMD soldiers were defecting to the CCP. The CCP encouraged this by treating any GMD troops that surrendered very well, either encouraging them to join the CCP army or helping them to make their way back to their homes. (Fairbank 336). In 1949, Chiang Kaishek and the remining GMD forces retreated to Taiwan and Mao Zedong declared the foundation of the People's Republic of China in Beijing.

Three Years of Disasters

As the leader of China, Mao initiated the Great Leap Forward, an economic plan intended to rapidly industrialize China's then largely rural economy. In the end it proved a ruinous failure, preventing the peasants from producing needed food and causing massive famines; up to 38 million starved to death or were killed for opposing the economic plan.

Cultural Revolution

In 1966, Mao instigated the Cultural Revolution, in which those disloyal to the Chairman were killed or humiliated in order to solidify Mao's control. Richard Nixon was the first United States president to meet with Mao, and thus the first to acknowledge the existence of the People's Republic of China, as opposed to Taiwan's Republic of China.

Mass murder

Overall, historians believe that around 43 million people died under Mao's rule, due mostly to starvation from disastrous socialist economic policies such as the "Great Leap Forward" but now known in China as The Three Years of Disaters. This is 7 times the common figure given for the Holocaust but it is much less known.

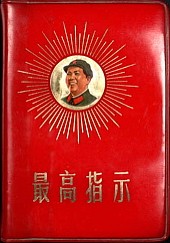

Little Red Book

Mao is the author of Quotations from Chairman Mao, published in 1966, informally known as "the little red book." During his lifetime, almost everyone in the People's Republic of China was expected to have a copy. One of his most well known statements was that "political power grows out of the barrel of a gun".

Legacy

In their book Mao: The Unknown Story, authors Jung Chang and Jon Halliday state that in his first five years of power, 700,000 were claimed by Mao to be dead, but another 700,000 died in local excesses and 700,000 committed suicide out of fear of Mao. During the Great Leap Forward, Mao deliberately killed peasants by shipping food to the USSR and Eastern Europe in exchange for aid in building arms plants. As well, Mao's plans for peasants to make steel and build canals meant that in 1959-60 nobody grew any food. Thus, the worst famine in history occurred. Huge numbers were killed by puppets of Mao in the Cultural Revolution, which actually was launched to get rid of Mao's rivals in the Chinese Communist Party.

Name: (Traditional Chinese: 毛澤東; Simplified Chinese: 毛泽东; Hanyu Pinyin: Máo Zédōng; Wade-Giles: Mao Tse-tung)

Further reading

- Chang, Jung and Jon Halliday. Mao: The Unknown Story, (2005), 814 pages, ISBN 0-679-42271-4

- Clark, Paul. The Chinese Cultural Revolution: A History (2008), a favorable look at artistic production excerpt and text search

- Dietrich, Craig. People's China: A Brief History, 3d ed. (1997), 398pp excerpt and text search

- Esherick, Joseph W.; Pickowicz, Paul G.; and Walder, Andrew G., eds. The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History. (2006). 382 pp. excerpt and text search

- Fairbank, John King and Goldman, Merle. China: A New History. (2nd ed. 2006). 640 pp. excerpt and text search

- Hsü, Immanuel Chung-yueh. The Rise of Modern China, 6th ed. (1999), highly detailed coverage of 1644-1999, in 1136pp. excerpt and text search

- Jian, Guo; Song, Yongyi; and Zhou, Yuan. Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. (2006). 433 pp.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick and Fairbank, John K., eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966-1982. (1992). 1108 pp.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick and Michael Schoenhals. Mao's Last Revolution. (2006).

- MacFarquhar, Roderick. The Origins of the Cultural Revolution. Vol. 3: The Coming of the Cataclysm, 1961-1966. (1998). 733 pp.

- Meisner, Maurice. Mao's China and After: A History of the People’s Republic, 3rd ed. (1999), dense book with theoretical and political science approach. excerpt and text search

- Schoppa, R. Keith. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. Columbia U. Press, 2000. 356 pp. online edition from Questia

- Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China (1991), 876pp; well written survey from 1644 to 1980s excerpt and text search; complete edition online at Questia

- Spence, Jonatham. Mao Zedong (1999) excerpt and text search

- Shuyun, Sun. The Long March: The True History of Communist China's Founding Myth (2007)

- Taylor, Jay. The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China (2009), 722 pp. highly favorable scholarly biography of Mao's great enemy

- Wang, Ke-wen, ed. Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism. (1998). 442 pp.

- Xia, Yafeng. "The Study of Cold War International History in China: A Review of the Last Twenty Years," Journal of Cold War Studies10#1 Winter 2008, pp. 81-115 in Project Muse

- Yan, Jiaqi and Gao, Gao. Turbulent Decade: A History of the Cultural Revolution. (1996). 736 pp.

- Studies of Modern Chinese History: Reviews and Historiographical Essays

References

- ↑ Red Star Over China by Edgar Snow, New York, 1937.