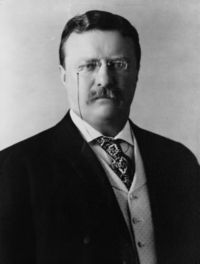

Theodore Roosevelt

| Theodore Roosevelt | |

|---|---|

| |

| 26th President of the United States | |

| Term of office September 14, 1901 - March 4, 1909[1] | |

| Political party | Republican |

| Vice Presidents | None (1901-1905) Charles W. Fairbanks (1905-1909) |

| Preceded by | William McKinley |

| Succeeded by | William Howard Taft |

| 25th Vice-President of the United States | |

| Term of office March 4, 1901 - September 14, 1901 | |

| President | William McKinley |

| Preceded by | Garret Hobart |

| Succeeded by | Charles W. Fairbanks |

| Born | October 27, 1858 New York, New York |

| Died | January 6, 1919 Oyster Bay, New York |

| Spouse | Alice Hathaway Lee Edith Kermit Carow |

| Religion | Dutch Reformed |

Theodore Roosevelt was the 26th President of the United States of America, 1901-1909, leader of the Republican party, and (in 1912-16) the Progressive Party. Roosevelt is best known for his remarkable personality and commitment to democratic process. He was strongly committed to law and order, active leadership, civic duty, and individual self-responsibility, and was more concerned with the process of change than its direction. A strong and vigorous man both personally and in politics, it was through Roosevelt that the world identified America with cowboy values of courage, initiative, and hardiness while directing greater involvment of the United States in world affairs. He strongly endorsed motherhood and criticized women who had careers while neglecting motherhood [2].

In the contest beteen Conservation and environmentalism, Roosevelt supported the conservation and optimum use of natural resources, and opposed the environmentalists of the day, such as John Muir.

Contents

Family

The Roosevelts could trace their family to Claes Martenssen van Rosenvelt, an immigrant from Zeeland, Holland (Netherlands) who came to America in 1649, settleing in New Amsterdam (New York City). Theodore was born was born on October 27, 1858, the second child of a very successful New York businessman, Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., and his wife Martha Bulloch, a Southern belle from Georgia. His early childhood was marked by frequent illness and asthma, of which his father spent many an evening bundling up "Teedie" - as young Theodore was often called - and taking him out for carriage rides in the fresh air. By age 10 his father would have enough of the possibility of his son growing into an unhealthy weakling, and forced on him a regimen of weights and daily physical excercise.

He suffered from asthma as a boy but was able to work through it with the assistance of exercise.

Nearly ten months after making this declaration of his enchantment with the young Alice Lee of Boston, Theodore Roosevelt married his "sweet life." Four years later, February brought tragedy; on February 14, 1884, Roosevelt's young wife died after giving birth to the couple's first child. Only a few hours earlier, his mother, Martha Bulloch Roosevelt had died in the same house. After the double funeral and the christening of his new baby daughter, Alice, on February 17, 1884, the bereaved husband wrote: [1]

- For joy or for sorrow my life has now been lived out.

Early career

He directed both the New York Police Department[3] and later, the Navy Department. He was appointed civil service commissioner by President Benjamin Harrison.

War with Spain, 1898

When the Spanish-American War started he resigned his assistant secretaryship in the Navy and became a rough rider.

Governor of new York

A war hero, Roosevelt was elected governor of New York as a Republican in 1898. The party bosses distrusted him, and they forced his nomination as vice president on William McKinley in 1900. Roosevelt campaigned energetically and was elected.

President

When President McKinley was fatally shot by an anarchist in 1901, Roosevelt automatically became President, and was reelected against a challenge by the Democratic candidate Alton B. Parker in 1904.

Foreign Policy

Roosevelt's administration was marked by an active approach to foreign policy. Roosevelt saw it as the duty of more developed ("civilized") nations to help the underdeveloped ("uncivilized") world move forward. In Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and the Panama Canal Zone, he used the Army's medical service, under Walter Reed and William C. Gorgas, to eliminate the yellow fever menace and install a new regime of public health. He used the army to build up the infrastructure of the new possessions, building railways, telegraph and telephone lines, and upgrading roads and port facilities.

Roosevelt dramatically increased the size of the navy, forming the new warships into a "Great White Fleet" for display purposes and sending it on a world tour in 1907. This display was designed as a show of force to impress the Japanese. Yet, the ships were almost forced to return because of the inadequacy of American ports in the Pacific.[4]

Roosevelt Corollary

The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine was a substantial expansion in 1904. Roosevelt asserted the right of the United States to intervene to stabilize the economic affairs of small nations in the Caribbean and Central America if they were unable to pay their international debts and were at risk of intervention by European powers. The new policy primarily prevented intervention by Britain and Germany, which loaned money to the countries that did not repay. The catalyst of the new policy was Germany's aggressiveness in the Venezuela affair of 1902-03. The intervention took the form of takeover of the customs collection, and disbursement of the funds to the debtors and claimants. The policy was unpopular abroad.[5]

Mitchener and Weidenmier (2006) show the economic benefits to the small countries. The average debt price for countries under the US "sphere of influence" rose by 74% in response to the pronouncement and actions to make it credible. That is, their bonds rose 74% because buyers now believed they would be repaid. The increase in financial stability reduced internal conflict because political factions could not count on winning control of the national treasury if they won a civil war. The program spurred export growth and better fiscal management, but debt settlements were driven primarily by gunboat diplomacy.[6]

Panama Canal

Roosevelt understood the strategic significance of the Panama Canal, which opened up the Pacific Coast and Asia to cheap shipping, and made it possible for the Navy to move between the Atlamntic and Pacific rapidly. He negotiated for the U.S. to take control of its construction in 1904; he felt that the Canal's completion was his most important and historically significant international achievement.

1912 election

When Roosevelt's term was up he decided not to run again but chose Secretary of War William Howard Taft as his successor. Long-term disputes inside the GOP, especially regarding tariffs and the tension between Eastern industry and Midwest agriculture, pulled tha party apart. TR broke with Taft in 1910 but was outmaneuvered by Taft, who won the GOP nomination in 1912. Roosevelt walked out of the convention and the party, running as an independent on his own "Progressive" ticket, nicknamed the "Bull Moose Party". Roosevelt was shot before giving in a speech in Milwaukee. The bullet lodged in a copy of the speech stuffed into his breast pocket, saving his life. He gave the speech anyway that day, beginning the speech with the famous line, "I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose."

Both he and Taft lost to Democrat Woodrow Wilson in the election of 1912. The Taft conservatives, however, kept control of the GOP.

Exploration

After leaving office, Roosevelt took a trip along the Amazon River and wrote a book about his experience, Through the Brazilian Wilderness. While in South America, Roosevelt contracted malaria and nearly died. At one point, he requested that his expedition leave him behind. His son, Kermit, helped nurse him back to help, and Theodore credited Kermit with saving his life.

Conservation

More than any president before or since, Roosevelt insisted that conservation of natural resources be high on the agenda. As a world-class hunter and explorer, he mobilized support among American hunters, fishermen and outdoorsmen. he promoted both the national park system and the national forest system.

In the early 20th century there were three main positions. The laissez-faire position held that owners of private property--including lumber and mining companies, should be allowed to do anything they wished for their property. The conservationists, led by Roosevelt and his ally Gifford Pinchot, said that was too wasteful and inefficient. In any case, they noted, most of the natural resources in the western states were already owned by the federal government. The best course of action, they argued, was a long-term plan devised by national experts to maximize the long-term economic benefits of natural resources. The third position, led by the Sierra Club, held that nature was almost sacred, and that man was an intruder. It allowed for limited tourism (such as hiking), but opposed automobiles in national parks. It strenuously opposed timber cutting on most public lands, and vehemently denounced the dams that Roosevelt supported for water supplies, electricity and flood control. Especially controversial was the Hetch Hetchy dam in Yosemite National park, which Roosevelt approved, and which supplies the water supply of San Francisco. To this day the Sierra Club and its allies want to dynamite Hetch Hetchy and restore it to nature.

Race and Ethnicity

Roosevelt was keenly sensitive to the issues surrounding race and ethnicity, particularly the heated debated on immigration restriction. He considered himself Dutch, not Anglo-Saxon . He welcomed the vitality of new immigration, while holding that America's first responsibility was to its literate, native-born, working poor. In balancing these competitive goals, the president backed legislation that limited the immigration of poverty- and disease-stricken people regardless of ethnicity. He blocked harsh anti-Japanese efforts in California, but negotiated an informal agreement whereby Japan would no longer send immigrants. During World War I he attacked certain "hyphenated Americans," especially German-Americans and Irish-Americans, saying they put loyalties to their homeland above American interests.[7]

Patriotism

Roosevelt once declared:[8]

- We must have but one flag. We must also have but one language. That must be the language of the Declaration of Independence, of Washington’s Farewell address, of Lincoln’s Gettysburg speech and second inaugural. We cannot tolerate any attempt to oppose or supplant the language and culture that has come down to us from the builders of this Republic.

In the last year of his life Roosevelt was quoted in the Kansas City Star newspaper about the need for truth in regards to the Presidency:

- The President is merely the most important among a large number of public servants. He should be supported or opposed exactly to the degree which is warranted by his good conduct or bad conduct, his efficiency or inefficiency in rendering loyal, able, and disinterested service to the Nation as a whole. Therefore it is absolutely necessary that there should be full liberty to tell the truth about his acts, and this means that it is exactly necessary to blame him when he does wrong as to praise him when he does right. Any other attitude in an American citizen is both base and servile. To announce that there must be no criticism of the president, or that we are to stand by the president, right or wrong, is not only unpatriotic and servile, but is morally treasonable to the American public. Nothing but the truth should be spoken about him or any one else. But it is even more important to tell the truth, pleasant or unpleasant, about him than about any one else.

Conservative or liberal?

Metaphorically, there were 15 different Roosevelts; conservatives admire 10 of them, liberals admire 10, with some overlap. Conservatives are more apt to admire his patriotism, masculinity and military achievements, his stress on national greatness, his buildup of the nation's military forces, his resolution of the 1902 Coal Strike without forcing business to recognize the unions, his attacks on hyphenated Americans (people with divided loyalty in wartime), and his bold histories of the frontier. Liberals are more likely to admire his trust-busting and hostility to big business, his promotion of liberal programs in 1907-8 and 1912, and his break with the GOP in 1912 when he denounced it as too conservative. Ronald Reagan noted in 1972, "I admire 'Teddy' greatly and quote him often."[9]

Conservation was always high on TR's agenda. His optimal use policy has largely been adopted by conservatives and businessmen, while the Sierra Club and related groups reject Roosevelt's policies.

Everyone admires his amazingly dynamic style and willingness to confront the issues of the day by bringing everyone to the negotiating table, his settlement of the war between Japan and Russia (which led to Roosevelt's winning the Nobel peace prize), and his building of the Panama Canal (though liberals complain he was too rough with Colombia).

Religion and character

Like his Roosevelt ancestors, Theodore Roosevelt was a member of the Dutch Reformed Church (denomination). His mother was a Presbyterian, another Calvinist denomination like the Reformed. In Oyster Bay there was no Reformed church, and so from 1887 onward he went to Christ Church (Episcopal) with his wife Edith and the children, where he took part in the service, loudly singing the hymns. But in Albany Roosevelt attended a Dutch Reformed church, while Edith went to an Episcopal church. In Washington he attended nearby Grace Reformed Church, a German Reformed church, close to the Dutch, while Edith, as First Lady attended St. John's Church, Lafayette Square (Episcopal), the "church of the presidents," across from the White House.[10] Relative little has been written on Roosevelt 's religion, although a book, ROOSEVELT'S RELIGION by Christian Reisner,[11] provides recollections from his friends and others on the subject.

Roosevelt provided Nine Reasons Why a Man Should Go to Church,[12] such as

- In this actual world, a churchless community, a community where men have abandoned and scoffed at or ignored their religious needs, is a community on the rapid down grade.

- He will listen to and take part in reading some beautiful passages from the Bible. And if he is not familiar with the Bible he has suffered a loss.

- He may not hear a good sermon at church. He will hear a sermon by a good man who, with his wife, is engaged all of the week in making hard lives a little easier.

- I advocate a man's joining in church work for the sake of showing his faith by his works.

Various other quotes[13][14] help express Roosevelt's character and values.

- A thorough knowledge of the Bible is worth more than a college education.

- There is not in all America a more dangerous trait than the deification of mere smartness unaccompanied by any sense of moral responsibility.[15]

- Alone of human beings the good and wise mother stands on a plane of equal honor with the bravest soldier; for she has gladly gone down to the brink of the chasm of darkness to bring back the children in whose hands rests the future of the years.[16]

- The one thing I want to leave my children is an honorable name."[17]

- It is better to be faithful than famous.

- There are good men and bad men of all nationalities, creeds and colors; and if this world of ours is ever to become what we hope some day it may become, it must be by the general recognition that the man's heart and soul, the man's worth and actions, determine his standing.[18]

- I have a perfect horror of words that are not backed up by deeds.[19]

- Men can never escape being governed. Either they must govern themselves or they must submit to being governed by others.[20]

- A vote is like a rifle: its usefulness depends upon the character of the user.[21]

- This country has nothing to fear from the crooked man who fails. We put him in jail. It is the crooked man who succeeds who is a threat to this country.[22]

- No man can lead a public career really worth leading, no man can act with rugged independence in serious crises, nor strike at great abuses, nor afford to make powerful and unscrupulous foes, if he is himself vulnerable in his private character.[23]

- Criticism is necessary and useful; it is often indispensable; but it can never take the place of action, or be even a poor substitute for it. The function of the mere critic is of very subordinate usefulness. It is the doer of deeds who actually counts in the battle for life, and not the man who looks on and says how the fight ought to be fought, without himself sharing the stress and the danger.(1894)

- I have never in my life envied a human being who led an easy life; I have envied a great many people who led difficult lives and led them well.[24]

- There is not a man of us who does not at times need a helping hand to be stretched out to him, and then shame upon him who will not stretch out the helping hand to his brother.[25]

- Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.

- It is hard to fail, but it is worse never to have tried to succeed.[26]

- The only man who makes no mistakes is the man who never does anything.

- ...any nation which in its youth lives only for the day, reaps without sowing, and consumes without husbanding, must expect the penalty of the prodigal whose labor could with difficulty find him the bare means of life.[27]

- Conservation means development as much as it does protection. I recognize the right and duty of this generation to develop and use the natural resources of our land; but I do not recognize the right to waste them, or to rob, by wasteful use, the generations that come after us."[28]

- Is America a weakling, to shrink from the work of the great world powers? No! The young giant of the West stands on a continent and clasps the crest of an ocean in either hand. Our nation, glorious in youth and strength, looks into the future with eager eyes and rejoices as a strong man to run a race.[29]

- Now to you men, who, in your turn, have come together to spend and be spent in the endless crusade against wrong, to you who face the future resolute and confident, to you who strive in a spirit of brotherhood for the betterment of our Nation, to you who gird yourselves for this great new fight in the never-ending warfare for the good of humankind, I say in closing what in that speech I said in closing: We stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord[30]

Trivia

The Teddy Bear is named for Theodore Roosevelt. After it was reported that Roosevelt had refused to shoot a bear on a hunting expedition a toy shop owner placed a sign next to a toy bear in his shop window announcing that this was "Teddy's Bear". The name stuck.

Roosevelt was not sworn in on a Bible. He remains the only president in history to do so.[31]

Notes

- ↑ http://home.comcast.net/~sharonday7/Presidents/AP060301.htm

- ↑ See "Theodore Roosevelt on Motherhood and the Welfare of the State," Population and Development Review, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Mar., 1987), pp. 141-147 online

- ↑ Roosevelt is the only president born in New York City, but Herbert Hoover and Richard Nixon lived there when they were elected.

- ↑ See Edward S Miller,War Plan Orange (Annapolis, 1991)

- ↑ Serge Ricard, "The Roosevelt Corollary." Presidential Studies Quarterly 2006 36(1): 17-26. Issn: 0360-4918, online

- ↑ Kris James Mitchener and Marc Weidenmier, "Empire, Public Goods, and the Roosevelt Corollary." Journal of Economic History 2005 65(3): 658-692. Issn: 0022-0507; online

- ↑ The German-Americans did not support Germany, but did want the U.S. to remain neutral. The Irish Catholics were so hostile to Britain that they did not want the U.S. to support it.

- ↑ Theodore Roosevelt, "The Children of the Crucible," 14 Annals of America 1916-1928, 129, at 130 (1968).

- ↑ Text in Ronald Reagan Reagan: A Life in Letters (2004) p 266

- ↑ THE RELIGION of THEODORE ROOSEVELT

- ↑ Extract and search

- ↑ http://www.theodoreroosevelt.org/life/Church9reasons.htm

- ↑ The Works of Theodore Roosevelt - National Edition, H-BAR Enterprises

- ↑ http://thinkexist.com/quotation/a_thorough_knowledge_of_the_bible_is_worth_more/164715.html

- ↑ Abilene, KS, May 2, 1903

- ↑ The Great Adventure, 1918

- ↑ Chicago, IL, April 10, 1899

- ↑ Letter, Oyster Bay, NY, September 1, 1903

- ↑ Oyster Bay, NY, July 7, 1915

- ↑ Jamestown, VA, April 26, 1907

- ↑ An Autobiography, 1913

- ↑ Memphis, TN, October 25, 1905

- ↑ An Autobiography, 1913

- ↑ Des Moines, Iowa, November 4, 1910

- ↑ Pasadena, CA, May 8, 1903

- ↑ Chicago, IL, April 10, 1899

- ↑ Arbor Day - A Message to the School-Children of the United States" April 15, 1907

- ↑ The New Nationalism" speech, Osawatomie, Kansas, August 31, 1910

- ↑ Letter to John Hay, American Ambassador to the Court of St. James, London, Written in Washington, DC, June 7, 1897

- ↑ A Confession of Faith, delivered in Chicago, Illinois, 6 August 1912

- ↑ Library of Congress Presidential Inauguration Precedents and Notable Events

Bibliography

Biographies

- Brands, H.W. T.R.: The Last Romantic (1998), scholarly biography online edition

- Chessman, G. Wallace. Theodore Roosevelt and the Politics of Power, (1969), short biography by scholar

- Cooper, John Milton The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt. (1983), well-written a dual scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- Dalton, Kathleen. Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life. (2002), full scholarly biography

- Harbaugh, William Henry. The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt. (1963), full scholarly biography

- Keller, Morton, ed., Theodore Roosevelt: A Profile (1967) excerpts from TR and from historians.

- McCullough, David. Mornings on Horseback, The Story of an Extraordinary Family. a Vanished Way of Life, and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt. (2001) popular biography to 1884

- Morris, Edmund. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, to 1901 (1979); vol 2: Theodore Rex 1901–1909. (2001); Pulitzer prize for Volume 1. Biography; unusually well-written and well-researched

- O'Toole, Patricia. When Trumpets Call: Theodore Roosevelt after the White House. (2005). 494 pp.

- Pringle, Henry F. Theodore Roosevelt (1932; 2nd ed. 1956), full scholarly biography online 1st edition

- Putnam, Carleton Theodore Roosevelt: A Biography, Volume I: The Formative Years (1958), only volume published, to age 28; written by prominent conservative

Scholarly studies

- Barsness,John A. "Theodore Roosevelt as Cowboy: The Virginian as Jacksonian Man." American Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Autumn, 1969), pp. 609-619 in JSTOR

- Blum, John Morton The Republican Roosevelt. (1954). Influential essays that examine how TR did politics

- Brinkley, Douglas. The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (2009), best coverage of TR and conservation

- Burton, David H. Taft, Roosevelt, and the Limits of Friendship, (2005) online edition

- Chace, James. 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft, and Debs - The Election That Changed the Country. (2004). 323 pp; popular account excerpt and text search

- Cutright, Paul Russell. Theodore Roosevelt: The Making of a Conservationist (1985)

- Dorsey, Leroy G., and Rachel M. Harlow, "'We Want Americans Pure and Simple': Theodore Roosevelt and the Myth of Americanism," Rhetoric & Public Affairs, Volume 6, Number 1, Spring 2003, pp. 55-78 in Project Muse

- Ellsworth, Clayton S. "Theodore Roosevelt's Country Life Commission." Agricultural History, Vol. 34, No. 4 (Oct., 1960), pp. 155-172 in JSTOR

- Dyer, Thomas G. Theodore Roosevelt and the Idea of Race (1980)

- Fehn, Bruce. "Theodore Roosevelt and American Masculinity." Magazine of History (2005) 19(2): 52–59. Issn: 0882-228x Fulltext online at Ebsco. Provides a lesson plan on TR as the historical figure who most exemplifies the quality of masculinity.

- Friedenberg, Robert V. Theodore Roosevelt and the Rhetoric of Militant Decency (1990) online edition

- Gerstle, Gary. "Theodore Roosevelt and the Divided Character of American Nationalism," The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 3, (Dec., 1999), pp. 1280-1307 in JSTOR

- Gosnell, Harold F. Boss Platt and His New York Machine: A Study of the Political Leadership of Thomas C. Platt, Theodore Roosevelt, and Others (1924) online edition

- Gould, Lewis L. The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. (1991), standard history of his domestic and foreign policy as president

- Gatewood, Willard B. "The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. by Lewis L. Gould" Reviews in American History, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Dec., 1992), pp. 512-517 in JSTOR

- Havig, Alan. "Presidential Images, History, and Homage: Memorializing Theodore Roosevelt, 1919-1967 ". American Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Autumn, 1978), pp. 514-532 IN jstor

- Johnson, Arthur M. "Theodore Roosevelt and the Bureau of Corporations". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 45, No. 4 (Mar., 1959), pp. 571-590 in JSTOR

- Millard, Candice. River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey. (2005), exploring the Amazon

- Mowry, George. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America, 1900–1912. (1954) general survey of era

- Mowry, George E. Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement. (2001) focus on 1912

- Mowry, George E. "Theodore Roosevelt and the Election of 1910," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Mar., 1939), pp. 523-534 in JSTOR

- Oyos, Matthew M. "Theodore Roosevelt, Congress, and the Military: U.S. Civil-Military Relations in the Early Twentieth Century," Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 30, 2000 online edition

- Powell, Jim. Bully Boy: The Truth About Theodore Roosevelt's Legacy (2006). Denounces TR policies from libertarian perspective

- Rhodes, James Ford. The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897-1909 (1922) online edition

- Scheiner, Seth M. "President Theodore Roosevelt and the Negro, 1901-1908," The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 47, No. 3 (Jul., 1962), pp. 169-182 in JSTOR

- Slotkin, Richard. "Nostalgia and Progress: Theodore Roosevelt's Myth of the Frontier," American Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 5, (Winter, 1981), pp. 608-637 in JSTOR

- Testi, Arnaldo. "The Gender of Reform Politics: Theodore Roosevelt and the Culture of Masculinity," The Journal of American History, Vol. 81, No. 4 (Mar., 1995), pp. 1509-1533 in JSTOR

- Watts, Sarah. Rough Rider in the White House: Theodore Roosevelt and the Politics of Desire. (2003). 289 pp.

Foreign and military affairs

- Beale Howard K. Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power. (1956). standard history of his foreign policy

- Buchanan, Russell. "Theodore Roosevelt and American Neutrality, 1914-1917," The American Historical Review, Vol. 43, No. 4 (Jul., 1938), pp. 775-790 in JSTOR

- Burton, David H. "Theodore Roosevelt: Confident Imperialist" The Review of Politics, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Jul., 1961), pp. 356-377 in JSTOR

- Burton, David H. "Theodore Roosevelt's Social Darwinism and Views on Imperialism," Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1965), pp. 103-118 in JSTOR

- Gould, Lewis L. The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. (1991), standard history of his domestic and foreign policy as president

- Holmes, James R. Theodore Roosevelt and World Order: Police Power in International Relations. 2006. 328 pp.

- Marks III, Frederick W. Velvet on Iron: The Diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt (1979)

- McCullough, David. The Path between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870–1914 (1977).

- Neu, Charles E. "Theodore Roosevelt and American Involvement in the Far East, 1901-1909," The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Nov., 1966), pp. 433-449 in JSTOR

- Oyos, Matthew M. "Theodore Roosevelt and the Implements of War," The Journal of Military History, Vol. 60, No. 4 (Oct., 1996), pp. 631-655 in JSTOR

- Ricard, Serge. "The Roosevelt Corollary." Presidential Studies Quarterly 2006 36(1): 17–26. Issn: 0360-4918 online edition

- Stillson, Albert C. "Military Policy Without Political Guidance: Theodore Roosevelt's Navy," Military Affairs, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Spring, 1961), pp. 18-31 in JSTOR

- Tilchin, William N. and Neu, Charles E., ed. Artists of Power: Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Their Enduring Impact on U.S. Foreign Policy. Praeger, 2006. 196 pp. online edition

- Tilchin, William N. Theodore Roosevelt and the British Empire: A Study in Presidential Statecraft (1997)

Primary sources

- Auchincloss, Louis, ed. Theodore Roosevelt, The Rough Riders and an Autobiography (Library of America, 2004) ISBN 978-1-93108265-5; Theodore Roosevelt, Letters and Speeches (Library of America, 2004) ISBN 978-1-93108266-2

- Brands, H.W. ed. The Selected Letters of Theodore Roosevelt. (2001)

- Butt, Archie. The Letters of Archie Butt, Personal Aide to President Roosevelt, (1924) online edition

- Gould, Lewis L., ed. Bull Moose on the Stump: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt. (2008). 256 pages,

- Harbaugh, William ed. The Writings Of Theodore Roosevelt (1967). A one-volume selection of Roosevelt's speeches and essays.

- Hart, Albert Bushnell and Herbert Ronald Ferleger, eds. Theodore Roosevelt Cyclopedia (1941), Roosevelt's opinions on many issues; online version at [2]

- Morison, Elting E., John Morton Blum, and Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., eds., The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, 8 vols. (1951–1954). Very large, annotated edition of letters from TR.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1999). Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography. online at Bartleby.com.

- Roosevelt, Theodore. The Works of Theodore Roosevelt (National edition, 20 vol. 1926); 18,000 pages containing most of TR's speeches, books and essays, but not his letters; a CD-ROM edition is available; some of TR's books are available online through Project Bartleby

- Theodore Roosevelt books and speeches on Project Gutenberg

- Roosevelt, Theodore. "Theodore Roosevelt on Motherhood and the Welfare of the State," Population and Development Review, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Mar., 1987), pp. 141-147 in JSTOR

- Shaw, Albert, ed. A Cartoon History of Roosevelt's Career (1910) full text and cartoons online

| |||||

| |||||