Difference between revisions of "Civil Rights Movement"

(→Non-black supporters) |

JohnJustice (Talk | contribs) m (→Modern Movement: grammar) |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

The Supreme Court under Chief Justice [[Earl Warren]], a liberal Republican, issued [[Brown vs. Board of education]] in 1954, declaring legal segregation to be unconstitutional. It marked the culmination of a judicial movement that had been underway for a decade. It had the short-term effect of ending segregated schools in border states, and the long-term effect of ending legalized segregation in schools. | The Supreme Court under Chief Justice [[Earl Warren]], a liberal Republican, issued [[Brown vs. Board of education]] in 1954, declaring legal segregation to be unconstitutional. It marked the culmination of a judicial movement that had been underway for a decade. It had the short-term effect of ending segregated schools in border states, and the long-term effect of ending legalized segregation in schools. | ||

| − | Presidents [[Dwight Eisenhower]] and [[John F. Kennedy]] to a | + | Presidents [[Dwight Eisenhower]] and [[John F. Kennedy]] to a lesser degree, and [[Lyndon Johnson]] to a major degree became proactive in the Civil Rights movement. Johnson in particular built a coalition that included white churches, Jews, and labor unions, as well as many Republicans such as [[Everett Dirksen]], to build a majority of the northern leadership in favor of action. The white South filibustered but failed stop passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended Jim Crow, and the [[Voting Rights Act]] of 1965, which guaranteed federal oversight of voting rights. |

| + | |||

| + | In 1957, Governor [[Orville Faubus]] of Arkansas mobilized the state National Guard to prevent a court ordered desegregation of Little Rock public schools. When the federal court issued an injunction Eisenhower intervened decisively, taking control of the National Guard and send in Army combat troops. He enforced the desegregation of schools. In the late 1960s several southern states expressed forceful opposition to what was considered Federal tyranny; some redesigned their state flags to include the old Confederate banner. In 1962, the prospect of a black student being admitted to the [[University of Mississippi]] resulted in campus riots suppressed by Federal troops and a national guard now brought under Federal control. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Black leaders== | ==Black leaders== | ||

Black leaders claimed that their own efforts were more important in causing change, emphasizing activities like bus boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins. A black Baptist minister from Atlanta [[Martin Luther King]] led the new movement. Painstaking work by labor unions, civil rights groups, and mainstream churches, aided by popular outrage at the violent techniques used by police in some southern cities fueled a national consensus that segregated and second class status had to end. Some of the organizations that spearheaded the movement were the [[Southern Christian Leadership Conference]] (SCLC), the [[Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee]] (SNCC, or 'Snick'), the [[Congress of Racial Equality]] (CORE), and the older [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP). All were committed to non-violence and Gandhian [[Civil Disobedience]] in the early years, a tactic that was politically essential in order to win public support and to avoid alienating northern voters. | Black leaders claimed that their own efforts were more important in causing change, emphasizing activities like bus boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins. A black Baptist minister from Atlanta [[Martin Luther King]] led the new movement. Painstaking work by labor unions, civil rights groups, and mainstream churches, aided by popular outrage at the violent techniques used by police in some southern cities fueled a national consensus that segregated and second class status had to end. Some of the organizations that spearheaded the movement were the [[Southern Christian Leadership Conference]] (SCLC), the [[Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee]] (SNCC, or 'Snick'), the [[Congress of Racial Equality]] (CORE), and the older [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP). All were committed to non-violence and Gandhian [[Civil Disobedience]] in the early years, a tactic that was politically essential in order to win public support and to avoid alienating northern voters. | ||

Revision as of 16:33, April 10, 2013

The civil rights movement was a movement towards racial equality and an end to segregation of African Americans that occurred in the United States from about 1953 to 1968, as courts and Congress made segregation illegal and imposed strict laws attempting to ensure that blacks could be able to vote.

Contents

Reconstruction and Jim Crow

During Reconstruction, Radical Republicans tried to guarantee equal rights for emancipated slaves after the American Civil War. They succeeded in passing the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments, which in theory required equal protection of the laws and an equal right to vote. President Ulysses Grant successfully suppressed the Ku Klux Klan when it used violence to turn back black gains. The Republican coalition in the South fell apart in the 1870s, and conservative white Redeemers took control. The Redeemers were paternalistic toward blacks but they confronted a Populist element in the 1890s that demanded strict segregation, called Jim Crow.

The Supreme Court allowed segregation in 1896, and black leaders such as Booker T. Washington worked to build an alliance of black businessmen and farmers with benevolent whites, using education as the tool to eventually achieve equality. Militant blacks led by W.E.B. DuBois and the NAACP demanded immediate redress. For a brief while around 1920 militant black separatists gained strength. While blacks slowly improved their economic status in the South in the 20th century, despite lynchings, they remained second class citizens with very little political power. Blacks began moving in large numbers to the North to meet the labor shortages during World War I and World War II. By the 1950s they had a political base in Harlem (New York City) and Chicago, but still very little power. Jim Crow remained as strong as ever in the South, where white Democrats had near-total control.

Modern Movement

The Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren, a liberal Republican, issued Brown vs. Board of education in 1954, declaring legal segregation to be unconstitutional. It marked the culmination of a judicial movement that had been underway for a decade. It had the short-term effect of ending segregated schools in border states, and the long-term effect of ending legalized segregation in schools.

Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy to a lesser degree, and Lyndon Johnson to a major degree became proactive in the Civil Rights movement. Johnson in particular built a coalition that included white churches, Jews, and labor unions, as well as many Republicans such as Everett Dirksen, to build a majority of the northern leadership in favor of action. The white South filibustered but failed stop passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended Jim Crow, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which guaranteed federal oversight of voting rights.

In 1957, Governor Orville Faubus of Arkansas mobilized the state National Guard to prevent a court ordered desegregation of Little Rock public schools. When the federal court issued an injunction Eisenhower intervened decisively, taking control of the National Guard and send in Army combat troops. He enforced the desegregation of schools. In the late 1960s several southern states expressed forceful opposition to what was considered Federal tyranny; some redesigned their state flags to include the old Confederate banner. In 1962, the prospect of a black student being admitted to the University of Mississippi resulted in campus riots suppressed by Federal troops and a national guard now brought under Federal control.

Black leaders

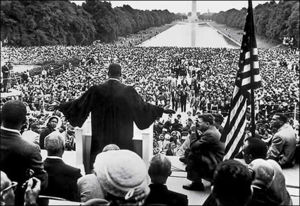

Black leaders claimed that their own efforts were more important in causing change, emphasizing activities like bus boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins. A black Baptist minister from Atlanta Martin Luther King led the new movement. Painstaking work by labor unions, civil rights groups, and mainstream churches, aided by popular outrage at the violent techniques used by police in some southern cities fueled a national consensus that segregated and second class status had to end. Some of the organizations that spearheaded the movement were the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, or 'Snick'), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the older National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). All were committed to non-violence and Gandhian Civil Disobedience in the early years, a tactic that was politically essential in order to win public support and to avoid alienating northern voters.

Black Power

Meanwhile a growing black radical movement, led by Muslims like Malcolm X, and inner city gangs, pulled the black community toward separatism. By 1966 the tensions inside the black community were ripping apart the civil rights coalition, as the radicals called for the ousting of all whites in leadership positions. King lost much of his influence, and was unable to stop the wave of rioting that broke out in every major American city with a black population. The riots soured white America on the civil rights movement because it brought violence and turmoil, and led to calls for Law and order.

Other groups

Other groups started to mobilize on behalf of their rights, especially feminists and Latinos, and later the homosexuals made a bid.

Civil Rights Leaders

Non-black supporters

See also

Further reading

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63 (1988)

- Graham, Hugh Davis. Civil Rights in the United States (1994)

- Graham, Hugh Davis. The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy, 1960-1972 (1990)

- Horton, James Oliver and Horton, Lois E. Hard Road to Freedom: The Story of African America. (2001). 405 pp. by leading black historians

- Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and its Troubled Legacy. (2001). 285 pp.

- Riches, William T. Martin. The Civil Rights Movement: Struggle and Resistance. (1997). 196 pp.

- Thernstrom, Stephan and Thernstrom, Abigail. America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible. (1997). 704 pp. by leading conservative scholars

- Verney, Kevern. Black Civil Rights in America. (2000). 135 pp.

Primary sources

- Birnbaum, Jonathan and Taylor, Clarence, eds. Civil Rights since 1787: A Reader on the Black Struggle. (2000). 935 pp.

- D'Angelo, Raymond, ed. The American Civil Rights Movement: Readings and Interpretations. (2001). 592 pp.