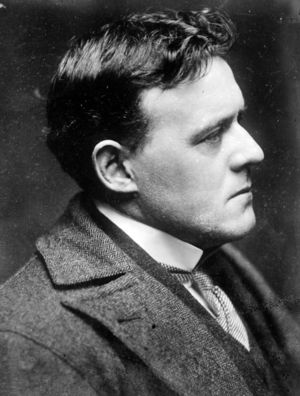

Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (1870-1953) was an English author. He wrote as Hilaire Belloc and is universally known under that name. (Joseph Belloc is generally unknown to lovers of English humorous verse.) His works include The Bad Child's Book of Beasts (1896), On Nothing (1908), Cautionary Tales for Children (1908), On Everything (1909), On Anything (1910).[1]

Life and Works

Belloc was born on July 27, 1870 in the village of La-Celle-Saint-Cloud, near Paris, before the Franco-Prussian War to a French lawyer and the English daughter of a Birmingham radical.[2] He was educated at both the Oratory School in Birmingham and Balliol College at Oxford, where he was president of a debating society.[3] He was a member of the Liberal Party of the British Parliament for five years, with strong views against capitalism, and was an aggressive debater with the Fabian Society, a pro-Socialist group where he met with such literary men as George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells, but later proved himself to be against socialism in his book, The Servile State.[4] He was a staunch Catholic, one of the "Big Four" men of English letters, and antagonized Islam though he spoke out against the Nazi treatment of the Jews.[5]

He married Elsie Hogan in 1896.[6] That same year, he published his first book, Verses and Sonnets, as well as The Bad Child's Book of Beasts.[7] The Bad Child's Book of Beasts is a picture book detailing various animals in large illustrations; the name "The Bad Child" is explained in the preface as referring to the typical Victorian child who does many things not condoned by his parents.[8] He was likely best known for a mocking of Victorian ideals, Cautionary Tales (1907).[9] After the success of his first works, he continued to work in politics and journalism, and as a novelist, writing Mr. Clutterbuck’s Election (1908), A Change in the Cabinet (1909), Pongo and the Bull (1910), and later as a historian, with The French Revolution (1911), and History of England (1915), which made him apt for the War Propaganda Bureau during World War One.[10]

In his later years, his incisive criticism of many British politicians as well as the party system rendered him unpopular, though he befriended writer G. K. Chesterton. He died after falling out of his chair while sleeping near his daughter's hearth, and burned in the flames, dying at a hospital in Surrey on July 16, 1953.[11]

References

- ↑ The New York Public Library Student's Desk Reference. Prentice Hall: New York, 1991.

- ↑ http://www.poetryarchive.org/poet/hilaire-belloc

- ↑ "Belloc, Hilaire." Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

- ↑ http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/joseph-hilaire-pierre-rene-belloc-1631.php

- ↑ http://www.poetryarchive.org/poet/hilaire-belloc

- ↑ https://www.poemhunter.com/hilaire-belloc/biography/

- ↑ https://www.poemhunter.com/hilaire-belloc/biography/

- ↑ Belloc, Hilaire. The Bad Child's Book of Beasts.

- ↑ http://school.eb.com/levels/high/article/Hilaire-Belloc/15291

- ↑ https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/hilaire-belloc

- ↑ http://www.catholicauthors.com/belloc.html

External links

- Extensive Biography on the Poetry Foundation website

- Poems