Difference between revisions of "Eamon de Valera"

(→Faith: ref for Jewish claim removing the rest) |

(→Civil War: art) |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

== Civil War == | == Civil War == | ||

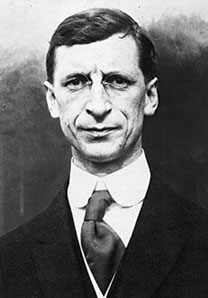

| − | The disagreement over the treaty ultimately escalated into the [[Irish Civil War]] in 1922-3. Although the new government attempted to avoid bloodshed, [[Winston Churchill]] threatened to reoccupy Ireland if they did not take action against anti-treaty forces who were headquartered in the Four Courts building in Dublin. De Valera backed the anti-treaty forces; he held no official position and had little influence, however. The pro-treaty forces of the new government, the [[Irish Free State]], had the support of most of the population, and were unable to fight effectively. On May 30, 1923, they were ordered to "dump arms". De Valera and many other anti-treaty leaders were arrested and interned; de Valera was released in 1924. | + | [[Image:DEVALERA2.JPG|thumb|210px]] The disagreement over the treaty ultimately escalated into the [[Irish Civil War]] in 1922-3. Although the new government attempted to avoid bloodshed, [[Winston Churchill]] threatened to reoccupy Ireland if they did not take action against anti-treaty forces who were headquartered in the Four Courts building in Dublin. De Valera backed the anti-treaty forces; he held no official position and had little influence, however. The pro-treaty forces of the new government, the [[Irish Free State]], had the support of most of the population, and were unable to fight effectively. On May 30, 1923, they were ordered to "dump arms". De Valera and many other anti-treaty leaders were arrested and interned; de Valera was released in 1924. |

== Fianna Fáil == | == Fianna Fáil == | ||

Revision as of 09:33, December 25, 2008

Éamon de Valera (New York, October 14, 1882 - Dublin, August 29, 1975) was a politician and mathematician, Prime Minister (Taoiseach) of Ireland from 1951-1959 and President from 1959-1973. He was an important figure in the Easter Rising, the Irish War for Independence (from the United Kingdom), and the Irish Civil War. De Valera dominated post-independence Irish politics for forty years.

Contents

Early Life

De Valera was born in New York City to an Irish mother, Catherine Coll de Valera, who had immigrated from County Limerick, and Vivion de Valera, a Spanish artist. Catherine and Vivion were married in September 1881 in Jersey City, NJ[1]. Vivion died in 1885, and the young Éamon went to live in Ireland with his uncle in Bruree, Limerick. At 16, de Valera enrolled at Blackrock College in Dublin, and won several scholarships and awards. In 1903 he was hired as a mathematics teacher at Rockwell College in County Tipperary. He later returned to teach at Blackrock College after earing a mathematics degree from the Royal University of Ireland.

Initial Political Activity

As a young man, he became an Irish Language activist, joining the Gaelic League in 1908, where he met Sinéad Flanagan, whom he married in January 1910. In 1913 de Valera joined the Irish Volunteers, a body formed to ensure the enactment of the Home Rule Act. He was voted a captain in 1914 and prior to the Easter Rising was commandant of the 3rd Battalion, Dublin Brigade and a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

Easter Rising

When the Rising began, on April 24, 1916, de Valera's forces occupied Boland's Mill in Dublin. There have been conflicting reports as to his performance during Easter Week; supporters claim he showed excellent leadership skills and tactical ability, while detractors claim that he suffered a nervous breakdown[2]. Following the rebels' surrender, de Valera was sentenced to death by the British. His sentence was commuted to life in prison largely as a result of his American citizenship and the fact that at the time the British were trying to convince the United States to join World War I and feared that his execution would inflame American public opinion. De Valera was released along with the other prisoners in June 1917.

War of Independence

In 1917 de Valera was elected to the House of Commons for East Clare in a special election to replace Willie Redmond, who was killed in World War I. In May 1918 he was imprisoned again, but was reelected in 1919 as a member of Sinn Féin, who won 73 of 105 Irish seats. In January 1919, the Sinn Féin representatives, who had refused to attend the House of Commons, formed an Irish parliament, Dáil Éireann, or Assembly of Ireland. De Valera escaped from jail in February 1919, and in April was elected Príomh Aire, or prime minister, of the Dáil. To raise money, seek official recognition of an Irish Republic, and obtain the support of the American people, de Valera visited the United States from June 1919 to December 1920. Though he raised $5.5 million, he was unable to secure official recognition from the US government.

De Valera returned in January 1921 to an Ireland in the midst of war. However, a truce was declared in July, and de Valera met with David Lloyd George, the British prime minister, on July 14, but a peace agreement could not be reached. Further negotiations took place from October through December 5, but de Valera did not participate, arguing that he was Irish head of state and should not participate unless the British head of state, King George V, was also present. The Irish delegates Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith, and Robert Barton ultimately negotiated a treaty that proved controversial, as it made Ireland a dominion of the Commonwealth, and agreed that the King would be represented in Dublin by a Governor-General. Additionally, the treaty allowed for the partition of Ireland. De Valera was unhappy with the terms; he claimed that he had not participated in negotiations in order to better maintain control of extremists in Ireland, while others claimed that he knew the likely outcome and avoided participation in order to avoid responsibility. His two primary problems with the treaty were: (1) it required members of the Dáil to swear loyalty to the King; (2) it allowed Britain to retain control over several naval ports, potentially preventing Ireland from having an independent foreign policy. The treaty passed the Dáil 64-57, at which point de Valera and many like-minded TDs resigned.

Civil War

The disagreement over the treaty ultimately escalated into the Irish Civil War in 1922-3. Although the new government attempted to avoid bloodshed, Winston Churchill threatened to reoccupy Ireland if they did not take action against anti-treaty forces who were headquartered in the Four Courts building in Dublin. De Valera backed the anti-treaty forces; he held no official position and had little influence, however. The pro-treaty forces of the new government, the Irish Free State, had the support of most of the population, and were unable to fight effectively. On May 30, 1923, they were ordered to "dump arms". De Valera and many other anti-treaty leaders were arrested and interned; de Valera was released in 1924.Fianna Fáil

After the Civil War ended, de Valera returned to politics. He resigned from Sinn Féin in 1926 and formed a new party, Fianna Fáil (Soldiers of Destiny). The party did well electorally but initially refused to take the oath to the King, beginning a case to challenge the legality of the oath. However, following the assassination of deputy prime minister Kevin O'Higgins in 1927, the case was dropped, and de Valera and his party took the oath and entered the Dáil.

Fianna Fáil became the dominant party in the Dáil after the 1932 general election, and de Valera was appointed prime minister. He quickly initiated an economic war against the UK that lasted until 1938, substantially damaging the Irish economy. Fianna Fáil won general elections in 1933, 1937, 1938, and 1943. His government generally worked toward dismantling the treaty with Britain. In 1937, de Valera enacted a new Irish constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, which resulted in a number of changes, including: (1) the name of the state was changed from the Irish Free State to Éire; (2) it was claimed that the national territory included Northern Ireland; (3) an elected President of Ireland replaced the British governor-general; (4) the "special position" of the Roman Catholic Church was recognized; (5) divorce was outlawed; (6) Irish was declared the first official language.

Later Years

De Valera and the Dáil nearly unanimously believed that neutrality during World War II was the best policy, although the government assisted in fighting fires in Belfast after a Luftwaffe raid. In 1945, de Valera was the only head of any state to extend condolences following Hitler's death.

Fianna Fáil was replaced in 1948 by a coalition government, but regained control in 1957. De Valera remained as Taoiseach (prime minister) until 1959, when he was elected President, an office from which he retired in 1973 at age 90. His son, Vivion de Valera, served in the Dáil, as did his granddaughter Sile de Valera. A grandson, Éamon Ó Cuív is a current TD.

Faith

de Valera was a devout Roman Catholic, although there was a rumour at one stage that his Father was Jewish. This has never been proven, although de Valera denounced the claim as "filthy propaganda'. [3]

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Ancient Order of Hibernians

- ↑ Coogan, T. P. (1993). De Valera: Long Fellow, Long Shadow. London: Hutchison.

- ↑ www.irishnews.com/pageacc.asp?tser1=ser&par=ben&sid=427856