Difference between revisions of "The Crusades"

(→The Third Crusade) |

|||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

== The Third Crusade == | == The Third Crusade == | ||

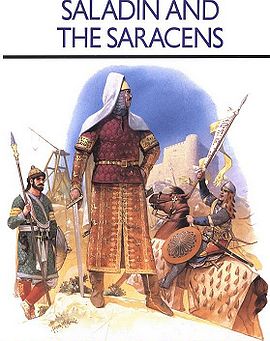

| − | The [[Third Crusade]] (1189-92) is famous for the battles between [[Richard I|Richard the Lionheart]] and [[Saladin]], highlighted by the deep respect the two enemies had for each other, and the sense of [[chivalry|chivalric]] honor of King Richard. The crusade also involved the king of France (who returned home after an argument with Richard at Acre) and the Holy Roman Emperor (who drowned en route). The crusade had the limited success of obtaining a truce between Richard and Saladin that promised to allow Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem. | + | [[File:Saladin2.jpg|thumb|left|270px]]The [[Third Crusade]] (1189-92) is famous for the battles between [[Richard I|Richard the Lionheart]] and [[Saladin]], highlighted by the deep respect the two enemies had for each other, and the sense of [[chivalry|chivalric]] honor of King Richard. The crusade also involved the king of France (who returned home after an argument with Richard at Acre) and the Holy Roman Emperor (who drowned en route). The crusade had the limited success of obtaining a truce between Richard and Saladin that promised to allow Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem. |

== The Fourth Crusade == | == The Fourth Crusade == | ||

Revision as of 20:46, May 7, 2009

| Part of the series on |

| The Middle Ages |

| Historical Periods |

|

Early Middle Ages (6th-10th century) |

| Medieval History |

|

Holy Roman Empire |

| Medieval Society |

The Crusades (1095-1291) were a series of wars conflicts fought between European Christians and Muslims to regain the Holy Land. They were the military responses made by Christians from western Europe to the pope's pleas to free the Holy Land from Islam. The First Crusade was a success and created up new Latin states in the Holy Land. Subsequent crusades were less successful except when they attacked Byzantium. Other medieval movements against heretics and infidels also were called crusaders, and they had permanent success. The crusades ended with the Islamic recapture of all the Holy Land in 1291, when the the last city controlled by crusaders, Acre, fell.

The crusades comprise a major chapter of Medieval History. Extending over three centuries, they attracted every social class in western Europe. Kings and commoners, barons and bishops, knights and commoners—even teenagers—all participated in these expeditions to the eastern end of the Mediterranean. The motives of the crusaders were numerous: some sought riches; many sought adventure; most were moved by faith alone. Historians stress the central role of religious fervor, while mentioning as well the socio-economic factors crucial in enticing larger contingents. For example, crusaders often were fulfilling their feudal obligations. There were strong links between the papal reforms, the social necessity of violence and the exploitation of this inherent revivalistic imagination of the age of the Papacy.[1]

The crusades failed to achieve the permanent control of the Holy Land. However, their influence was wide and deep. Much of the crusading fervor carried over to the successful fights against the Moors (Muslims) in Spain and the pagan Slavs in eastern Europe. Politically the crusades weakened the decrepit Byzantine Empire, but temporarily kept the Muslims away from it. The First Crusade strengthened the moral leadership of the papacy in Europe, but the failures of the later crusades weakened both the crusading ideal and respect for the papacy Contact with the East widened the scope of the Europeans, ended their isolation, and exposed them to an rich civilization. The economic effects of the crusades were modest, but they did reopen of the eastern Mediterranean to Western commerce, which itself had an effect on the rise of great cities such as Venice and the emergence of a money economy in the West.

The crusaders derived their name from the Latin word for "cross"--crux. A crusader went to the Holy Land with a cross of cloth sewn over his breast; when he returned, he had a similar cross for his back. Originally called to repel the Islamic forces that controlled Jerusalem, the crusades evolved into a form of political decree called by the Papacy for political, social or economic reasons. The campaigns of Teutonic knights against pagan strongholds in Eastern Europe are also sometimes called crusades. Lastly, military actions within Christendom against heretical and schismatic groups are sometimes called a crusade. Thus a crusade in most general terms was a directive of war issued by the pope to all Rome-friendly nations against forces, whether Muslim, pagan or Eastern Orthodox, which were hostile to the Papacy.

The crusades in the Holy Land ultimately failed to establish permanent Christian kingdoms. The fourth crusade resulted in a very damaged relationship between Greek and Latin Christendom. Islamic expansion into remained a threat for centuries, with crusading orders establishing strongholds to protect Mediterranean islands.

On the other hand, the crusades in southern Spain were militarily successful, eventually leading to the end of Islamic power in the region in 1492. The Teutonic knights expanded Christian domains in Eastern Europe, and the Albigensian Crusade, achieved its goal of destroying heretics in France. [2]

Contents

Holy Land Crusades

The Holy Land had been part of the Roman Empire, and thus the Byzantine Empire, until the Islamic conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries that forced the Byzantines out and saw the area gradually turn Islamic. Calm returned and Christians had generally been permitted to visit the sacred places in the Holy Land until 1071, when the Seljuk Turks assailed the Byzantines, defeating them at the Battle of Manzikert, and conquered Jerusalem from the Egyptian Fatimids the same year. They were not friendly to Christian pilgrims, in contrast to how the Fatimids had been, and soon pilgrims came under threat of robbery or even death as they were no longer welcome. The Byzantine Emperor Alexius I asked for aid from the west both to the Popes and the Christian monarchs. Nothing meaningful happened. Alexius may have been hoping for money from the pope for the hiring of mercenaries. Instead, Urban II called upon the knights of Christendom to fight for the defense of the Christian East and the protection of pilgrims in a speech made at the Council of Clermont on November 27, 1095. Urban demanded that all internal feuds within Christendom end, threatening excommunication for anyone who continued to bicker internally, and promising absolution and assurance of salvation to anyone who died in the crusade. In a sense this matched the claims that Islam made in regard to Jihad since the inception of that religion. This time Europe listened. Those who were there erupted in spontaneous cries of "Deus le vult!" ("God wills it!") - which would become the watchword of what we now know as the Crusades.

Nothing like this had previously been done, and the Pope himself had no military power so to speak and had to count on those who were in positions of power to supply it. While the monarchs of Europe did not get directly involved, it was a series of prominent nobles who answered the call, among the most famous being: the Norman Bohemund of Taranto, former claimant to the Duchy of Apulia, his nephew Tancred, Count Raymond of Toulouse, Duke Godfrey de Bouillon of Lorraine, Duke Hugh of Vermandois (brother of the King of France), Duke Robert of Normandy, and Count Robert of Flanders. The spiritual leader who would accompany meet and accompany them was French Bishop Adhemar du Puy, who was appointed Papal legate. All that was known at the start was that the forces to participate would meet together in Constantinople. Alexius had no idea what was being unleashed.

Others took matters into their own hands. The peasantry, stirred by the preaching of the layman Peter the Hermit, embarked on a disorganized and poorly supplied “crusade”, which failed utterly, being rather unwelcome in the cities they stopped in on their journey, and being slaughtered by the first Islamic army they met. This was an unofficial, impromptu affair involving the peasantry, and which was warned, and forbidden, by the Christian feudal lords and the papacy alike, but to which they paid no heed.

A smaller group of peasants led by Gottschalk took out their fervor on a more local target, the Jewish communities of Lotharingia. Their actions were condemned by the Church and the local populace.[3][4] A much larger threat against Jews took the form of a larger mob led by Count Emico of Leiningen, who was more organized and more brutal. Already a man with a sullied reputation, he ignored the pleas of the Bishops in town after town to desist. Apart from being hidden by the local populace when they heard Emico was coming, there was little the Jews could do. Previously in Europe, local difficulties against Jewish communities would rise from time to time in various places, but would be isolated to that local area. This started a phase not previously seen, a systematic effort to weed out and attack Jewish communities.

The First Crusade

The First Crusade, properly speaking, was lead by Feudal lords, mostly of Frankish origin. Many of the knights left home never expecting to return, knowing virtually nothing about the Holy Land, and trusting in God for victory. The army consisted of almost 20,000 men, including a mass of squires and other servants necessary to support a mounted knight. Arriving at Constantinople the force, which eventually reached almost 50,000 total men, was not what the Byzantine Emperor Alexius had expected. He had hoped for a few thousand well trained mercenaries to help him retake his lands from the Turks, and had little in common with the goal of 'freeing the Holy Land'. An uneasy tension ensued from 1096 to 1097 as the forces gathered, but through a combination of firmness and diplomacy, Alexius avoided serious complications. In return for his assurance of assistance, he obtained oaths of allegiance from the Crusader leaders, and their promise that they would help recapture Nicaea from the Turks and return to him any other former possessions which they conquered. Alexius then transported them across the Bosporus - being careful not to allow any large number of Crusader forces inside the walls of his capital at any given time. He also provided them with food and with an escort of Byzantine troops to guide them towards their objectives (and incidentally to prevent Crusader plundering).[5]

After a hard march to the Holy Land, the army captured invested Nicaea in 1097. By a combination of skillful fighting and skillful diplomacy, Alexius arrange for the surrender of the city to him after a successful Crusader-Byzantine assault on the outer walls. The Crusaders were upset at Alexius' refusal to give them permission to sack the city.

The Crusaders continued to the southeast in parallel columns, without any one commander in charge. After fighting the inconclusive Battle of Dorylaeum, the army split in half. Tancred and Baldwin, brother of Godfrey of Lorraine and future King of Jerusalem, went east took the Armenian fortress-city of Edessa - an action that destroyed the support of many local Armenian Christians for the Crusade, and weakened it's internal bonds, as Balwin and Tancred's men clashed over possession of the city, with Baldwin emerging triumphant. The main body of the army continued onward and besieged Antioch. The city was surrounded for 8 months from October 21, 1097 to June 3, 1098. Two relieving armies were driven off in the Battles of Harenc in December and February. Due to poor arrangements for supplies, the Crusading army was actually close to starvation, but was saved by the fortuitous arrival of English and Pisan flotillas which seized two nearby ports and brought provisions. Bickering among the Crusader leaders, especially Bohemund and Raymond was rampant. The initiative of Bohemund led to the capture of Antioch just 2 days before a relieving army of 75,000 strong under the atabeg of Mosul, Kerboga would arrived, delayed itself after a fruitless three-week long attempt to dislodge Baldwin from Edessa.

Now it was the Crusaders turn to be trapped inside the city as Kerboga sieged Antioch from June 5, to June 28, 1098. The Crusaders were cut off from supplies and again near starvation. A Byzantine army was coming to take the city as agreed, but hearing that the Crusaders were doomed, turned back to Constantinople. It was then the 'Holy Lance' was discovered; the weapon said to have pierced Jesus' side. While few historians or theologians believe this miraculous discovery was valid, it energized the Crusader army at just the time they needed it. The Battle of the Orontes was fought on June 28 where 15,000 Crusaders left Antioch to battle and drove off the entire Moslem army and broke the siege, helped in part by the decision of several of the local emirs serving under Kerbogha to abandon him during the battle, fearing that he coveted their territory.

Due to internal bickering, many of the Crusaders did not continue on to Jerusalem. The force that arrived in June 1099 was only about 12,000 strong, far fewer than the army of defenders. They sieged the city from June 9 to July 18. Realizing they didn't have enough men to keep out supplies and starve the defenders, they boldly attacked. Overrunning the city, many of the inhabitants were massacred, including other Christians. A relieving force of 50,000 strong arrived in August to fight the Crusaders, but were routed at the Battle of Ascalon. The military aspects of the First Crusade had ended.

Four feudal kingdoms were established, which would remain for nearly 100 years. Several Military Orders, consisting of paladins, were also set up within the next few years, focusing mainly around the protection of the welfare of pilgrims and the defense of Christendom within the framework of an orgainsation that was both spiritual and martial in nature. The best known of these orders were the Knights of the Temple, or Templars, and the Knights of the Hospital of St. John, or Hospitallers. The Hospitallers still exist today in the form of the Order of Malta and St. John's Ambulance.

The Second Crusade

The Second Crusade occurred in 1145 when Edessa was retaken by Islamic forces. It was ultimately a failure, owing in part to the French king's insistence on betraying and attacking his only Muslim ally, Damascus. In 1187 the Muslims captured Jerusalem under their leader Saladin, which brought about a new call for a Crusade.

The Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189-92) is famous for the battles between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin, highlighted by the deep respect the two enemies had for each other, and the sense of chivalric honor of King Richard. The crusade also involved the king of France (who returned home after an argument with Richard at Acre) and the Holy Roman Emperor (who drowned en route). The crusade had the limited success of obtaining a truce between Richard and Saladin that promised to allow Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem.The Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade, begun by Innocent III in 1202, intended to retake the Holy Land but was soon subverted by Venetians who used the forces to sack the Christian city of Zara. Innocent excommunicated the Venetians and crusaders. Eventually the crusaders arrived in Constantinople, but due to strife which arose between them and the Byzantines, rather than proceed to the Holy Land the crusaders instead sacked Constantinople and other parts of Asia Minor effectively establishing the Latin Empire of Constantinople in Greece and Asia Minor . Both Zara and Constantinople were Christian cities, and the ultimate effect was a severely damaged relationship between Greek and Latin Christendom.

This was effectively the last crusade sponsored by the papacy; later crusades were sponsored by individuals.

The Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade and the Crusade of St. Louis both nearly succeeded in regaining Jerusalem by way of attacking Egypt and failed only through the greed of men like Robert of Artois.

Legends tell of a so-called Children's Crusade, where a mass of peasant children, enthused at the notion of a holy war, embarked to the Holy Land, only to be captured by greedy Genovese merchant men and sold into slavery before ever leaving Europe. Historians, though divided, generally consider this event to be a fiction.

Aftermath

Thus, though Jerusalem was held for nearly a century and other strongholds in the Near East would remain in Christian possession much longer, the crusades in the Holy Land ultimately failed to establish permanent Christian kingdoms. It should be noted that, in explaining why the crusaders ultimately failed, contemporary churchmen pointed out the sins of the crusaders. Islamic expansion into Europe, while temporarily stalled, would renew and remain a threat for centuries with the disintegration of the Byzantine Empire and culminate with the campaigns of Suleiman the Magnificent in the sixteenth century.

References

- ↑ Douglas James, "Christians and the First Crusade," History Review, (Dec 2005), Issue 53

- ↑ See Brian Tierney and Sidney Painter, Western Europe in the Middle Ages 300–1475. 6th ed. (McGraw-Hill 1998)

- ↑ The Age of Faith, Will Durant, 1950, Pg. 589

- ↑ Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Crusades: a History. 2005: Yale University Press. ISBN: 0300101287

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Military History, Dupuy & Dupuy, 1979, Pg. 312-313