History of Sweden

Contents

Middle Ages

During the seventh and eighth centuries, the Swedes were merchant seamen well known for their far-reaching trade. In the ninth century, Nordic Vikings raided and ravaged the European continent as far as the Black and Caspian Seas. During the 11th and 12th centuries, Sweden gradually became a unified Christian kingdom that later included Finland. Until 1060 the Svear kings of Uppsala ruled most of modern Sweden except the southern and western coastal regions, which remained under Danish rule until the 17th century. After a century of civil wars a new royal family emerged, which strengthened the power of the crown at the expense of the nobility, while giving the nobles privileges such as exemption from taxation in exchange for military service. Finland was taken over. Sweden never had a fully developed feudal system, and its peasants were never reduced to serfdom.

The first Christian missionary, Ansgar (801-865) made repeated trips to Sweden at the request of the king. In 1008 King Olaf Skötkonung (980-1022) was baptized and the great pagan temple at Uppsala was destroyed; Swedes slowly gave up paganism and became Catholics. St. Bridget (Birgitta) (1303-1373) is the patron saint of Sweden. She was lady-in-waiting at the royal court, and in response to her many visions and revelations, she founded the double order of monks and nuns, known as the Bridgettines. In her Revelations, many of them of a political nature, St. Bridget provided Sweden with its greatest piece of medieval literature

Queen Margaret of Denmark united all the Nordic lands in the "Kalmar Union" in 1397, by which Denmark dominated Sweden. The Swedish nobles, without a king of their own, resisted leading to open conflict in the 15th century.

Reformation

The Kalmar Union's final disintegration in the early 16th century brought on a long-lived rivalry between Norway and Denmark on one side and Sweden and Finland on the other. The Catholic bishops had supported Danish King Christian II, but he was overthrown by Gustavus Vasa (1490-1560) and Sweden (with Finland) was now independent again. Gustavus used the Protestant Reformation to curb the power of the church and became King Gustavus I in 1523. In 1527 he persuaded the Riksdag of Västerås, (comprising the nobles, clergy, burghers, and freehold peasants), to confiscate the church lands, which comprised 21% of the farmland. Gustavus patronized the Lutheran reformers and appointed his men as bishops. Gustavus suppressed aristocratic opposition to his ecclesiastical policies and centralization efforts.

Tax reform took place in 1538 and 1558, whereby multiple complex taxes on independent farmers were simplified and standardized throughout the district; tax assessments per farm were adjusted to reflect ability to pay. Crown tax revenues increased but more important the new system was much fairer and more acceptable. A war with Luebeck in 1535 resulted in the expulsion of the Hanseatic traders, who previously had a monopoly of foreign trade. With its own businessmen in charge, Sweden's economic strength grew rapidly and by 1544 Gustavus controlled 60% of the farmlands in all of Sweden. Sweden now built the first modern army in Europe, supported by a sophisticated tax system and government bureaucracy. Gustavus proclaimed the Swedish crown hereditary in his family, the house of Vasa. It ruled Sweden (1523-1654) and Poland (1587-1668).[1]

Early Modern

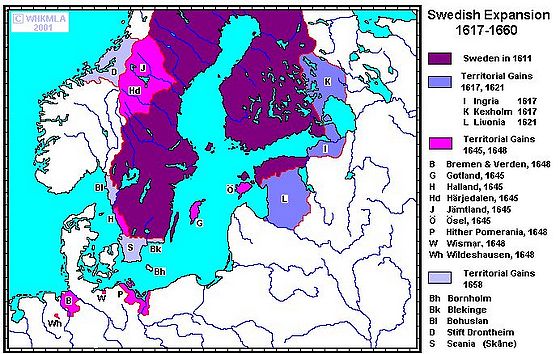

In the 16th century, Gustav Vasa fought for an independent Sweden, crushing an attempt to restore the Kalmar Union and laying the foundation for modern Sweden. At the same time, he broke with the Catholic Church and established the Reformation. Lutheranism became the state religion. During the 17th century, after winning wars against Denmark, Russia, and Poland, Sweden-Finland (with scarcely more than 1 million inhabitants) emerged as a great power by taking direct control of the Baltic region, which was Europe's main source of grain, iron, copper, timber, tar, hemp, and furs.

Sweden's role in the Thirty Years War under King Gustavus Adolphus (1594 - 1632) determined the political as well as the religious balance of power in Europe. A notable military victory for Gustavus Adolphus was the battle of Breitenfeld (1631). With a superb military machine with good weapons, excellent training, and effective field artillery, all backed by a highly efficient government back home that paid the bills on time. Gustavus Adolphus was poised to make himself a major European leader, but he was killed in battle in 1632. Axel Oxenstierna (1583-1654), leader of the nobles, took charge and continued the war in alliance with France. In 1643, Sweden invaded Denmark, which had been defeated earlier by the emperor's forces, and forced the surrender of Gotland and the province of Halland. By the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Sweden also acquired Western Pomerania and control of the mouths of the Elbe and Weser rivers. Thus Sweden ruled several provinces of Denmark as well as what is now Finland, Ingermanland (in which St. Petersburg is located), Estonia, Latvia, and important coastal towns and other areas of northern Germany and was the dominant power in the north of Europe. However a long series of wars gradually put overwhelming demands on Sweden's small but prosperous economy. The population was only 1.4 million in 1720, the great majority were farmers.

Russia, Saxony-Poland, and Denmark-Norway pooled their power in 1700 and attacked the Swedish-Finnish empire. Although the young Swedish King Charles XII (1682-1718; reigned 1697-1718) won spectacular victories in the early years of the Great Northern War, most notably in the stunning success against the Russians at the Battle of Narva (1700), his plan to attack Moscow and force Russia into peace proved too ambitious.

The Russians won decisively at Poltava in June 1709, capturing much of the exhausted Swedish army. Charles XII and the remnants of his army were cut off from Sweden and fled south into Ottoman territory, where he remained three years. He outstayed his welcome, refusing to leave until the Ottoman Empire joined him in a new war against Tsar Peter I of Russia. In order to force the recalcitrant Ottoman government to follow his policies, he established, from his camp, a powerful political network in Constantinople, which was joined even by the mother of the sultan. Charles's persistence worked, as Peter's army was checked by Ottoman troops. However, Turkish failure to pursue the victory enraged Charles and from that moment his relations with the Ottoman administration soured. During the same period the behavior of his troops worsened and turned disastrous. Lack of discipline and contempt for the locals soon created an unbearable situation in Moldavia. The Swedish soldiers behaved badly, destroying, stealing, raping, and killing. Meanwhile, back in the north Sweden was invaded and defeated by its enemies; Charles returned home in 1714, too late to restore his lost empire and impoverished homeland; he died in 1718.[2] In the subsequent peace treaties, the allied powers, joined by Prussia and England-Hanover, ended Sweden's reign as a great power. Russian now dominated the north. The war-weary Riksdag asserted new powers and reduced the crown to a constitutional monarch, with power held by a civilian government controlled by the Riksdag. A new "Age of Freedom" opened, and the economy was rebuilt, supported by large exports of iron and lumber to Britain.[3]

The reign of Charles XII (1697-1718) has stirred great controversy; historians have been puzzled ever since why this military genius overreached and greatly weakened Sweden. Although most early-19th century historians tended to follow Voltaire's lead in bestowing extravagant praise on the warrior-king, others have criticized him as a fanatic, a bully, and a bloodthirsty warmonger. A more balanced view suggests a highly capable military ruler whose oft-reviled peculiarities seemed to have served him well, but who neglected his base in Sweden in pursuit of foreign adventure.[4] Slow to learn the limits of Sweden's diminished strength, a party of nobles, who called themselves the "Hats", dreamed of revenge on Russia and ruled the country from 1739 to 1765; they engaged in wars in 1741, 1757, 1788, and 1809, with more or less disastrous results as Russian influence grew after every Swedish defeat.

Enlightenment

Sweden shared in the Enlightenment culture of the day in the arts, architecture, science and learning. A new law in 1766 established for the first time the principle of freedom of the press—a notable step towards liberty of political opinion. The Academy of Science was founded in 1739 and the Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities in 1753. The outstanding cultural leader was Carl Linnaeus (1707–78), whose work in biology and ethnography had a major impact on European science.

King Gustav III (1746-1792) came to the throne in 1771, and in 1772 led a coup d'état, with French support, that established him as an "enlightened despot," who ruled at will. The Agre of Freedom and bitter party politics was over. Precocious and well educated, he became a patron of the arts and music. His edicts reformed the bureaucracy, repaired the currency, expanded trade, and improved defense. The population had reached 2.0 million and the country was prosperous, although rampant alcoholism was a growing social problem. But when Gustav made war on Russia and did poorly he was assassinated by a conspiracy of nobles angry that he tried to restrict their privileges for the benefit of the peasant farmers. This period of Swedish history has been characterised by the Gustavian Period in which Sweden was renowned for its culture and style. An folksy example of this style has been portrayed in their furnishing. In particular the uniqueness of their Swedish Mora Clock is symbolic of the individuality of Sweden at this time.

Urbanization

Between 1570 and 1800 Sweden experienced two periods of urban expansion, ca. 1580-1690 and in the mid-18th century, separated by relative stagnation from the 1690s to about 1720. The initial phase was the more active, including an increase in the percentage of urban dwellers in Stockholm - a pattern comparable to increasing urban populations in other European capital and port cities - as well as the foundation of a number of small new towns. Increasing populations in the small towns of the north and west characterized the second period of urban growth, which began around 1750 in response to shifts in Swedish trade patterns from the Baltic to the North Atlantic.[5]

19th century

Sweden suffered further territorial losses during the Napoleonic wars and was forced to cede Finland to Russia after the Finnish War (1808-1809). The following year, French Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte was elected Crown Prince as Karl Johan by the Riksdag (parliament). In 1813, his forces joined the allies against Napoleon. The Congress of Vienna compensated Sweden for its lost German territory through a merger of the Swedish and Norwegian crowns in a dual monarchy. Sweden's last war was fought in 1814. It was a brief confrontation with Norway to restrain their demands for independence. The war resulted in Norway entering into union with Sweden, but with its own constitution and parliament. The Sweden-Norway union was peacefully dissolved at Norway's request in 1905.

The constitution of 1809 was revolutionary because it rested on popular sovereignty rather than the authority of the king. The Riksdag, although not yet democratic, was supreme and modern Sweden, in a constitutional sense, was begun.

Economy

Sweden's predominantly agricultural economy shifted gradually from village to private farm-based agriculture during the Industrial Revolution, but this change failed to bring economic and social improvements commensurate with the rate of population growth. About 1 million Swedes immigrated to the United States between 1850 and 1890.

Colonies

Sweden experimented briefly with overseas colonies, including "New Sweden" in Colonial America in the 1640s. Sweden purchased the small Caribbean island of Saint Barthélemy from France in 1784, then sold it back in 1878; the population included slaves until they were freed by the Swedish government in 1847.[6]

Sweden's king became king of Norway in 1814, but Norway was largely independent of Sweden. The king's rule was not well received and when Sweden refused to allow Norway to have its own diplomats, Norway rejected the King of Sweden in 1905 and selected its own king.

Liberal reform

The 19th century was marked by the emergence of a liberal opposition press, the abolition of guild monopolies in trade and manufacturing in favor of free enterprise, the introduction of taxation and voting reforms, the installation of a national military service, and the rise in the electorate of three major party groups—Social Democratic Party, Liberal Party, and Conservative Party.

Health

The steady decline of death rates in Sweden began about 1810. For men and women of working age the death rate trend diverged, however, leading to increased excess male mortality during the first half of the century. There were very high rates of infant and child mortality before 1800, Among infants and children between the ages of one and four smallpox peaked as a cause of death in the 1770s-1780s and declined afterward. Mortality also peaked during this period due to other air-, food-, and waterborne diseases, but these declined as well during the early 19th century. The decline of several diseases during this time created a more favorable environment that increased children's resistance to disease and dramatically lowered child mortality.[7]

The introduction of compulsory gymnastics in Swedish schools in 1880 rested partly on a long tradition, from Renaissance humanism to the Enlightenment, of the importance of physical as well as intellectual training. More immediately, the promotion of gymnastics as a scientifically sound form of physical discipline coincided with the introduction of conscription, which gave the state a strong interest in educating children physically as well as mentally for the role of citizen soldiers.[8] Skiing is a major recreation in Sweden and its ideological, functional, ecological, and social impact has been great on Swedish nationalism and consciousness. Swedes perceived skiing as virtuous, masculine, heroic, in harmony with nature, and part of the country's culture. A growing awareness of strong national sentiments and an appreciation of natural resources led to the creation of the Swedish Ski Association in 1892 in order to combine nature, leisure, and nationalism. The organization focused its efforts on patriotic, militaristic, heroic, and environmental Swedish traditions as they relate to ski sports and outdoor life.[9]

20th century

During and after World War I, in which Sweden remained neutral, the country benefited from the worldwide demand for Swedish steel, ball bearings, wood pulp, and matches.

Welfare State

Swedish integration of socialism and democracy was successful because of the unique way in which Sweden's labor leaders, politicians, and classes cooperated during the early development period of Swedish social democracy. Because Sweden's socialist leaders chose a moderate, reformist political course with broad-based public support in the early stages of Swedish industrialization and prior to the full-blown development of Swedish interclass politics, Sweden escaped the severe extremist challenges and political and class divisions that plagued many European countries that attempted to develop social democratic systems after 1911. By dealing early, cooperatively, and effectively with the challenges of industrialization and its impact on Swedish social, political, and economic structures, Swedish social democrats were able to create one of the most successful social democratic systems in the world, with no signs of repression or totalitarianism.[10]

When the Social Democratic Party came into power in 1932, its leaders introduced a new political decision-making process, which later became known as "the Swedish model." The party took a central role, but tried as far as possible to base its policy on mutual understanding and compromise. Different interest groups were always involved in official committees that preceded government decisions.

Foreign policy concerns in the 1930s centered on Soviet and German expansionism, which stimulated failed efforts at Nordic defense cooperation. Sweden followed a policy of armed neutrality during World War II (although thousands of Swedish volunteers fought in the Winter War against the Soviets); however, it did permit German troops to pass through its territory to and from occupation duties in its neighbour, Norway, and it supplied the Nazi regime with steel and much needed ball-bearings.

Recent history

Sweden for 200 years has been nonaligned and avoided all wars; it sat out the Cold War as a neutral. Its cultural and economic ties were very largely with Western Europe and Communism had very little support.

Postwar prosperity provided the foundations for the social welfare policies characteristic of modern Sweden.

Despite extensive social welfare programs, financed by high taxes on individuals, Sweden remains a capitalist country, and the main industries and banks are privately owned. Sweden enjoyed excellent economic performance until the world crisis of the 1970s, after that, economic efficiency declined considerably. Prior to 1983, Sweden and other northern European social democracies experienced full employment, large social benefits, modest income inequality, and a near total abolition of poverty. After 1983 unemployment became a major problem. The distance between the political parties narrowed after 1968, as the Social Democrats and the middle class parties grew more similar.

Sweden became a member of the European Union (EU) in 1995. In September 2003 Sweden held a referendum on entering the European Monetary Union. The Swedish people rejected participation, with 56% voting against and 42% for, and the issue of adopting the Euro has not been reopened.

Politics

The Social Democratic Party was the largest party after 1914 and alone or at the head of a coalition governed almost continuously from 1932 to 1976. From 1946 to 1969 Tage Fritjof Erlander was party leader and prime minister; was the architect of Sweden's social welfare state. He was succeeded in 1969 by Olof Palme, who was prime minister until 1976 when a non-socialist conservative coalition (Moderates, the Center Party, the Liberals and the Christian Democrats) took office. Palme headed a Social Democratic minority government from 1982. Palme was assassinated in 1986; Ingvar Carlsson then led the party until its electoral defeat in 1991 and brought it back to power at the head of a minority government in 1994. The Social Democrats are closely tied to the labor unions and 90% of Swedish workers belong to a union. In 1991 they suffered their worst defeat in half a century, but in 1994 and 1998 elections they rebounded. As in many countries, New Left and environmental (Green) forces emerged in the 1970s; in recent elections each wins 5% to 10% of the vote. The Left Party emerged from Communism and frequently joins in Social Democrat coalitions.

The Moderate Party, founded in 1904 as the Conservative Party, pushes for more privatization of state-owned businesses and in the early 1990s gained support from outside its traditional stronghold of big business. It helped form nonsocialist coalition governments from 1976 to 1981, and its leader, Carl Bildt, was Sweden's prime minister from 1991 to 1994, the first Moderate in the post since 1930. The party's support ranges between 15 and 25 percent of the vote in recent decades. The Center Party, formerly known as the Farmers' Union, or the Agrarians, represents rural and agricultural interests, and has seen its share of the vote fall steadily to below 10% as rural Sweden loses population. The People's Party (formally the Liberal People's Party), founded in 1902, takes conservative positions. Its its roots are in the temperance movement and the nonconformist churches. It is known for pro-American and anti-Communist positions.

Sunce the 2006 elections Sweden has been governed by a center-right coalition.

Population change

Since 1930, emigration has been slight. About 15,000-30,000 people left Sweden annually after 1965. Sweden welcomed refugees and displaced persons at the end of World War II. Because of the low birth rate, immigration accounted for 45% of population growth between 1945 and 1980. By 1991, 9% of the population had been born abroad. After 1980 immigration again increased rapidly, mostly because of new refugees, reaching more than 60,000 annually by 1990. The increase stirred some anti-immigrant feeling. In 1994 there were 508,000 foreign nationals in Sweden, concentrated mainly in the larger cities. The largest groups were Finns (210,000), Yugoslavs (70,000), Iranians (48,000), Norwegians (47,000), Danes (41,000), and Turks (29,000). Aliens may vote in Swedish local elections after three years of legal residence

Sweden became highly urbanized after World War II, reaching 83% urban in 1990 and 85% today. As recently as 1940 only 38% of the population lived in urban areas, and in 1860, before industrialization, the proportion was only 11%. Large-scale movement from the countryside to the United States ended about 1900. Since 1945 the movement to Swedish cities has accelerated and has brought about a population decline in many areas, especially in the north. Most cities are small. Only 10 cities have populations of more than 100,000. The Stockholm metropolitan areas has a population of 2 million; Gothenburg has 906,000 in its metropolitan area and Malmö (including Lund) has 260,000, while the educational center of Uppsala has 130,000. The only large city in the north is Sundsvall (95,000 in metro area), which grew with the development of the forest industries in the 19th century and now is also a data processing center.

See also

Bibliography

Surveys

- Andersson, Ingvar. A History of Sweden (1956) online edition

- Derry, Thomas Kingston. A History of Scandinavia: Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Iceland. (1979). 447 pp.

- Kent, Neil. A Concise History of Sweden (2008), 314pp excerpt and text search

- Magnusson, Lars. An Economic History of Sweden (2000) online edition

- Moberg, Vilhelm, and Paul Britten Austin. A History of the Swedish People: Volume 1: From Prehistory to the Renaissance, (2005); A History of the Swedish People: Volume II: From Renaissance to Revolution (2005)

- Nordstrom, Byron J. The History of Sweden (2002) excerpt and text search

- Scott, Franklin D. Sweden: The Nation's History (1988), survey by leading scholar; excerpt and text search

- Sprague, Martina. Sweden: An Illustrated History (2005) excerpt and text search

- Warme, Lars G., ed. A History of Swedish Literature. (1996). 585 pp.

Pre 1700

- Forte, Angelo. Oram, Richard. Pedersen, Frederik. Viking Empires. (2005)

- Hudson, Benjamin. Viking Pirates and Christian Princes: Dynasty, Religion, and Empire in North America. (2005).

- Moberg, Vilhelm, and Paul Britten Austin. A History of the Swedish People: Volume 1: From Prehistory to the Renaissance, (2005)

- Österberg, Eva. Mentalities and Other Realities: Essays in Medieval and Early Modern Scandinavian History. Lund U. Press, 1991. 207 pp.

- Österberg, Eva and Lindström, Dag. Crime and Social Control in Medieval and Early Modern Swedish Towns. (1988). 169 pp.

- Porshnev, B. F. and Paul Dukes, eds. Muscovy and Sweden in the Thirty Years' War, 1630-1635. (1996). 256 pp.

- Roberts, Michael. The Early Vasas: A History of Sweden 1523-1611 (1968)

- Roberts, Michael. From Oxenstierna to Charles XII. Four Studies. (1991). 203 pp.

- Roberts, Michael. The Swedish Imperial Experience, 1560-1718. (1979). 156 pp.

Since 1700

- Chatterton, Mark. Saab: The Innovator. (1980). 160 pp.

- Frängsmyr, Tore, ed. Science in Sweden: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, 1739-1989. (1989). 291 pp.

- Fry, John A., ed. Limits of the Welfare State: Critical Views on Post-War Sweden. (1979). 234 pp.

- Gustavson, Carl G. The Small Giant: Sweden Enters the Industrial Era. (1986). 364 pp.

- Hodgson, Antony. Scandinavian Music: Finland and Sweden. (1985). 224 pp.

- Hoppe, Göran and Langton, John. Peasantry to Capitalism: Western Östergötland in the Nineteenth Century. (1995). 457 pp.

- Lewin, Leif. Ideology and Strategy: A Century of Swedish Politics. (1988). 344 pp.

- Metcalf, Michael F., ed. The Riksdag: A History of the Swedish Parliament. (1987). 347 pp.

- Misgeld, Klaus; Molin, Karl; and Amark, Klas. Creating Social Democracy: A Century of the Social Democratic Labor Party in Sweden. (1993). 500 pp.

- Moberg, Vilhelm, and Paul Britten Austin. A History of the Swedish People: Volume II: From Renaissance to Revolution (2005)

- Olsen, Gregg M. "Half Empty or Half Full? the Swedish Welfare State in Transition." Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology. v. 16 #2 (1999) pp 241+. online edition

- Palmer, Alan. Bernadotte: Napoleon's Marshal, Sweden's King. (1991). 285 pp.

- Pred, Allan. Lost Words and Lost Worlds: Modernity and the Language of Everyday Life in Late Nineteenth-Century Stockholm. (1990). 298 pp.

- Pred, Allan Richard. Place, Practice and Structure: Social and Spatial Transformation in Southern Sweden, 1750-1850. (1986). 268 pp.

- Roberts, Michael. The Age of Liberty: Sweden, 1719-1772. (1986). 233 pp.

- Söderberg, Johan et al. A Stagnating Metropolis: The Economy and Demography of Stockholm, 1750-1850. (1991). 234 pp.

External links

- History of Sweden

- F19, Swedish Volunteer Unit in Finland during the Winter War

- source for parts of this article; not copyright

References

- ↑ Michael Roberts, The Early Vasas: A History of Sweden 1523-1611 (1968); Jan Glete, War and the State in Early Modern Europe: Spain, the Dutch Republic, and Sweden as Fiscal-Military States, 1500-1660 (2002) War+and+the+State&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=OkIWbv60os&sig=F66lMnhInY-bydmQNc1V_mtSJeM&hl=en&ei=DAUCSv7tCJOCtgOFso3xBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1 online edition

- ↑ He was shot through the head during a siege, but whether by assassination at close range or by stray enemy fire at long range is mysteriously unclear. Andersson, A History of Sweden p 247

- ↑ Absolute monarchy returned briefly at the end of the 18th century.

- ↑ R. M. Hatton, Charles XII of Sweden (1968)

- ↑ Sven Lilja, "Swedish Urbanization c. 1570-1800: Chronology, Structure and Causes," Scandinavian Journal of History 1994 19 (4): 277-308.

- ↑ Francine M. Mayer, and Carolyn E. Fick, "Before and After Emancipation: Slaves and Free Coloreds of Saint-Barthelemy (French West Indies) in The 19th Century." Scandinavian Journal of History 1993 18 (4): 251-273.

- ↑ Jan Sundin, "Child Mortality and Causes of Death in a Swedish City, 1750-1860." Historical Methods 1996 29(3): 93-106.

- ↑ Jens Ljunggren, "Nation-Building, Primitivism and Manliness: The Issue of Gymnastics in Sweden around 1880". Scandinavian Journal of History 1996 21 (2): 101-120.

- ↑ Sverker Sörlin, "Nature, Skiing and Swedish Nationalism." International Journal of the History of Sport 1995 12(2): 147-163.

- ↑ Jae-Hung Ahn, "Ideology and Interest: The Case of Swedish Social Democracy, 1886-1911." Politics & Society 1996 24(2): 153-187.