Labor unions and racism

|

Despite contemporary left-wing propaganda equating "labor rights" with civil rights, labor unions and racism have a long, entrenched history.[1][2] According to Andrew Syrios of the Mises Institute:[3]

| “ | Nativism is usually associated with the right, but that shouldn’t be the case for these [old-school] progressives. The AFL supported the 1882 and 1924 immigration restriction acts against the Chinese. In fact, many “progressive” labor unions were very racist, nativist, and nationalist. Even the second incarnation of the Ku Klux Klan in the early twentieth century, aside from being quite racist, was also in favor of many progressive reforms. | ” |

| —Mises Institute, July 22, 2014 | ||

Contents

Timeline

Pre-1865: labor unions oppose abolitionist movement

During the antebellum years prior to the abolishing of slavery in the United States, labor unions employed economic propaganda favoring the continued enslaving of blacks in the South, claiming that the classical liberal concept of free labor would create "wage slavery" for whites.[1] Paul D. Moreno writes:[4]

| “ | In colonial and antebellum America, groups of white workers often petitioned state and local governments to eliminate competition from free black workers. Organized labor was largely hostile to the antislavery movement, and most abolitionists opposed unions. Understandably, white workers feared competition from emancipated slaves, and white workers in the North especially feared an influx of southern freedmen. | ” |

| —Cato Journal, Vol. 30, No. 1: "Unions and Discrimination," p. 69 | ||

In essence, labor unionists expressed similar, if not identical sentiments held by direct defenders of slavery, namely Democratic politician John C. Calhoun, denouncing "wage slavery" resulting from capitalism as more morally reprehensible in comparison to chattel slavery.[5] Free labor was deemed "exploitative," while the welfare system of slavery was presented, ironically, as compassionate for the enslaved—this stance was viewed by abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison as a defense of slavery. Union leaders were prominent for attacking abolitionists as lacking the enlightenment to agree with their anti-capitalist viewpoints.[5]

President Abraham Lincoln's expressed public support during the American Civil War for the colonization of blacks was an expedient appeal to unionist whites who feared that a free-market system would lower their wages by allowing blacks to equally compete in the job market.[4]

1870s: Reconstruction Era

- For a more detailed treatment, see Reconstruction.

According to liberal historian Eric Foner, labor union movements during the Reconstruction Era were founded on racial prejudice:[6]

| “ | ... Nor did organized labor give evidence of racial inclusiveness. In California, where indentured Chinese immigrants by 1870 constituted a quarter of the wage labor force, the agitation for their exclusion, more than any other issue, shaped the labor movement's development. | ” |

| —"Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877," p. 479 | ||

Anti-Asian antipathy, exclusion against blacks

Labor unions were not only rabidly bigoted towards Asian immigrants, as they also exhibited antiblack racism. Almost all labor unions nationwide during the time period prohibited black membership—the postbellum National Labor Congresses either instituted segregation of local black members or ignored the prospect of allowing blacks to join.[6] Labor leaders were also wont to aligning with Andrew Johnson, considered of the nation's most virulent racists to ever become president; a Cincinnati worker referred to him as "the old tailor." Johnson even won his first-ever election to any political office as a member and founder of a local organized labor party.[7]

The faction of the labor movement which favored the recruitment of black members were less concerned with civil rights than their own interests. The president of the Iron Moulder's Union, William H. Sylvis, made recruitment efforts in the South on a tour in 1869, though attacked the Freedmen's Bureau's as a "huge swindle upon the honest workingmen of the country," denouncing carpetbaggers as the instigators of the region's downtrodden economy.[8]

As a result of labor unionist racism, blacks rejected "talk of independent labor politics," eschewing alignment with other left-wing agendas like the issuing of greenbacks, supported by the populist white working-class but opposed by the Grant Administration.[8]

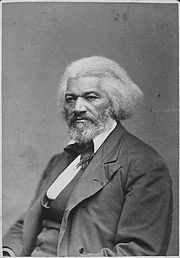

Frederick Douglass denounces labor unions

In 1874, Frederick Douglass wrote an essay/editorial titled "The Folly, Tyranny, and Wickedness of Labor Unions."[2][5] This was motivated by his personal experience with unionist antiblack racism firsthand, once working in New Bedford as a ship caulker where whites recommended that their black counterparts be reduced to unskilled labor. Douglass's son Lewis was ostracized by a typographers union in Washington, D.C., because of his work in Denver as a nonunion member.[9]

Gilded Age

Labor union support for the Chinese Exclusion Act

- For a more detailed treatment, see Chinese Exclusion Act.

Moreno writes, "Organized labor led the movement for the restrictions on Asian immigration in the 19th century," quoting economist Selig Perlman: "The anti-Chinese agitation in California, culminating as it did in the Exclusion Law of 1882, was undoubtedly the most important single factor in the history of American labor, for without it the entire country might have been overrun by Mongolian labor, and the labor movement might have become a conflict of races instead of one of classes."[10]

Unions supported maximum-hour laws targeting only women, decreasing the employment and wages of immigrant women who worked.[10] In New York, unions used such laws against immigrant bakers, which were later struck down by the United States Supreme Court in Lochner v. New York.

1898 Virden Massacre

The Illinois coal strike of 1898, also known as the Battle of Virden or the Virden Massacre, was a culmination of labor tensions which exacerbated into a white supremacist massacre of blacks. The United Mine Workers (UMW) striked from their mining jobs following the expiration of an agreement with the mine owners, and viciously suppressed blacks from taking their roles.[11] The Virden Coal Company and other anti-union forces arranged for the transportation of black strikebreakers from Alabama, who subsequently faced violent attacks by the strikers.[12]

Illinois Gov. John R. Tanner, who supported the rioting unionists, declared that any train transporting black workers would be shot "to pieces with Gatling guns,"[11] adding that "if any Negroes are brought into Pan awhile I am in charge, and they refuse to retreat when ordered to do so, I will order my men to fire." Tanner, indicted by a grand jury for exacerbating the tension, was extolled in a resolution passed by the American Federation of Labor. In addition, Mother Jones praised Illinois as "the best organized labor state in America."[11]

Progressive Era

- For a more detailed treatment, see Progressive Era.

In contrast to the pro-business nature of the Gilded Age, the Progressive Era marked a rise in labor unionism as an outgrowth of disdain towards classically liberal Yankee capitalism. As a result, racial discrimination against blacks increased due to the empowerment of labor unions increasingly by federal and state governments.[15] As blacks moved out of the South and sought economic self-betterment, competition in the job market culminated in eventual race riots.[15]

Amidst the closing of World War I, blacks advocated "open shops," opposed by labor unions who supported "industrial democracy."[15] A. Philip Randolph, a black socialist and later noted civil rights leader, denounced the AFL as "the most wicked machine for the propagation of race prejudice in the country." When blacks broke the Steel Strike of 1919, Communist William Z. Foster branded them collectively as "a race of strikebreakers."[15]

Later by 1924, the NAACP reported, "[the] white union labor does not want black labor, and, secondly, black labor has ceased to beg admittance to union ranks because of its increasing value and efficiency outside of the unions."

1920s

Second Ku Klux Klan

A common mainstream myth propagated by modern liberals to discredit "right-to-work" laws is that the Second Ku Klux Klan allegedly was opposed to labor unions. However, this relies on extremely cherry-picked distortions of the 1920s, as massive evidence indicates that the Klan, contrary to espousing viewpoints designated as "anti-union," were instead favorable towards labor reforms benefiting the white working class against competition. Historian Thomas R. Pegram writes:[16]

| “ | Historians usually consider the revived Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s to have been consistently opposed to labor unions and the aspirations of working-class people. The official outlook of the national Klan organization fits this characterization, but the interaction between grassroots Klan groups and pockets of white Protestant working-class Americans was more complex. [emphasis added] Some left-wing critics of capitalism singled out the Klan as a legitimate if flawed platform on which to build white working-class unity at a time when unions were weak and other institutions demonstrated indifference to working-class interests. | ” |

According to Pegram, actions towards labor unions by the Second Klan were ultimately motivated on basis of race/ethnicity, not labor itself, supporting strikes as an economic attack against blacks, Catholics, and immigrants, but repressing any which served to destabilize white Protestants.[16] Although the Klan has been painted as "anti-socialist," they were in fact competitors competing with the Socialist Party for the same working-class votes particularly in the Midwest—Morrison I. Swift concurred with the Klan's xenophobic bigotry, particularly their advocacy to "stop this stream of undesirables and thus prevent the glutting of the American labor market."

Klan support or opposition towards labor was highly regional—although Northeastern factions opposed strikes because unions there were primarily immigrant-comprised, ethnic, and Catholic, the KKK in the South and Midwest aligned with the interests of the white working class. Pegram further notes,[16]

| “ | Temporary political alliances between the Klan and white Protestant workers had improved public schools, taxed corporations, and challenged elite control of public policy in several communities. In the same fashion, some local Klans opportunistically intervened on behalf of striking white workers. The railroad shopmen's strike that interrupted nationwide rail traffic through the summer and autumn of 1922 exemplifies selective strike support by Klansmen. The northeastern Oregon town of La Grande was a railroad repair and maintenance center. Over one-third of the town's Klansmen were railroad workers, concentrated in nonstriking craft unions. Nevertheless, the La Grande klavern strongly supported the strike. One of its members served on the town strike committee, while the klavern investigated four local strikebreaking Knights. White Protestant identity rather than economic solidarity principally motivated Ku Klux activism. La Grande Klansmen issued their harshest condemnation against the four hooded strikebreakers for “teaching Negroes and Japs to take places of strikers.” | ” |

Although the hierarchy of the Socialist Party bitterly opposed the Klan, the socialist working-class whites were prone to influence by the Second KKK due to both groups presenting nearly identical appeals for the same constituency,[16] much as Nazis vs. Communists or Stalinists vs. Trotskyites are less ideological opposites than they are brotherhood competitors. Socialist appeals to labor unions were blunted by Klan efforts to win them to their side, notably when its national leader D. C. Stephenson called the KKK "the greatest friend that organized labor has in America today." A black committeeman for the Socialist Party of Indiana insisted that the Second Klan was "working for the things that the Socialist party want but cannot get."[16]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Moreno, Paul D., (2010). Cato Journal, Vol 30, No. 1: Unions and Discrimination, p. 67. Cato Institute. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Williams, Walter E. (September 20, 2017). The Black Family Is Struggling, and It’s Not Because of Slavery. The Daily Signal. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ↑ Syrios, Andrew (July 22, 2014). A Brief History of Progressivism. Mises Institute. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Unions and Discrimination," p. 69.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Unions and Discrimination," p. 70.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, p. 479. Internet Archive. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ↑ https://talkelections.org/FORUM/index.php?topic=473485.50

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution," p. 480.

- ↑ "Unions and Discrimination," p. 71.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Unions and Discrimination," p. 72.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Unions and Discrimination," p. 68.

- ↑ Laslett, John H. M. (2000). Colliers Across the Sea: A Comparative Study of Class Formation in Scotland and the American Midwest, 1830-1924, p. 260.

- ↑ 1923. Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life: Volumes 8–9, p. 272. Google Books. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ↑ Reyes, G. Mitchell (2010). Public Memory, Race, and Ethnicity, p. 55. Google Books. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Unions and Discrimination," p. 74.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Pegram, Thomas R. (April 27, 2018). The Ku Klux Klan, Labor, And The White Working Class During The 1920s. Cambridge University Press via Internet Archive. Retrieved May 27, 2023.