Difference between revisions of "Russian sanctions"

m |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

As trade ties between Russia and the [[EU]] were severed, Central Asian EU-trade increased to allow the reexport of EU goods (including dual use) to Russia. Trade with [[Kazakhstan]], [[Kyrgyzstan]] and [[Uzbekistan]] increased. The Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) became an effective mechanism for sanctions avoidance. | As trade ties between Russia and the [[EU]] were severed, Central Asian EU-trade increased to allow the reexport of EU goods (including dual use) to Russia. Trade with [[Kazakhstan]], [[Kyrgyzstan]] and [[Uzbekistan]] increased. The Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) became an effective mechanism for sanctions avoidance. | ||

| − | To give one example, German luxury car export to Kyrgyzstan increased by 31,000%. | + | To give one example, German luxury car export to Kyrgyzstan increased by 31,000%.<ref>[https://theprint.in/world/is-russia-evading-western-sanctions-via-central-asia-what-eu-trade-data-suggests/1885912/ 31,000% surge in car, ship, toy exports — Europe’s suddenly trading with Central Asia post Russia war], NIKHIL RAMPAL, ''The Print'', 15 December, 2023. theprint.in</ref> A major Russian [[gas]] deal with Uzbekistan and a $6bn [[coal]] deal with Kazakhstan, where almost 50% of foreign companies registered are now Russian, attest to an intensification of ties. Additionally, the multi-modal Middle Corridor was expected to replace the sanctioned Northern Corridor running through Russia. But the Middle Corridor still faces infrastructure bottlenecks and the Northern Corridor now transits pre-war volumes again. Central Asian [[migrant]] [[labor]] remittances increased, constituting 20% of Uzbek GDP, and higher percentages in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and [[Tajikistan]]. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 21:33, April 17, 2024

Russian sanctions were imposed at the outset of the NATO war in Ukraine.

In the third week of February 2022, socialist leader Joe Biden said that "As a result of these unprecedented sanctions, the ruble almost is immediately reduced to rubble," and push the Russian economy from being the 11th biggest in the world to outside the top 20. The UK Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary variously said that sanctions would take "the wheels off the Russian war machine," and "hobble" its economy. EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said "Russian industry is in tatters."[1] The EU said that sanctions were designed to erode "sharply Russia's economic base." The sanctions, which were unprecedented in size and scope, were meant to damage the Russian economy to such an extent that Moscow would be unable to continue its intervention in the Donbas war and perhaps even lead to regime change. Many experts agreed, forecasting a catastrophic effect on the Russian economy. The Institute of Financial Studies predicted a 15% fall in GDP. A Yale study went even farther, arguing that Russia had lost foreign business presence in the country that accounted for 40% of its GDP, and that there was "no path out of economic oblivion for Russia."

Instead, Russian GDP declined only 2.1% in 2022, a mild recession by emerging market standards. By 2023, the IMF expected the Russian economy to return to growth, and indeed outperform the economies of Germany, Britain and France. Clearly, the sanctions failed.

The obvious reason for the failure was a fundamental misunderstanding of the size, development and importance of the Russian economy. The idea that Russia was "a gas station with nukes," had sunk into the Western received wisdom. Former President Barack Obama said that "Russia doesn't make anything," while the idea that Russia's economy was "about the size of Italy's" was commonplace, adding to the sense that Russia would be an economic pushover.

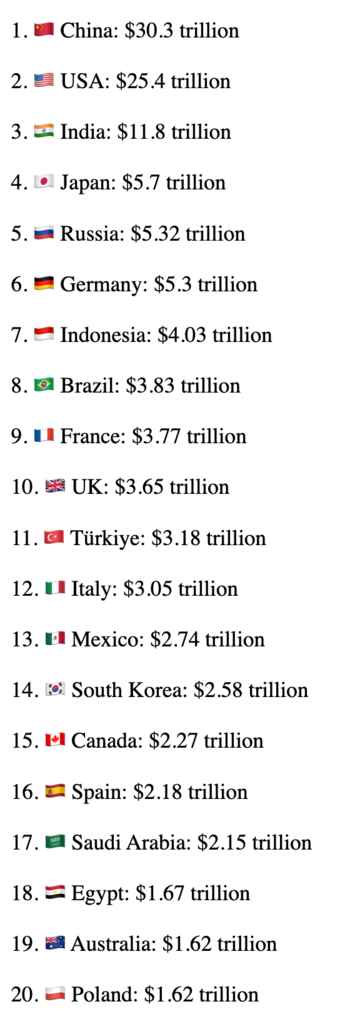

It is true that in nominal terms Russia's economy was only a little larger than Italy's before the beginning of Russia's Special Military Operation. Nominal GDP, however, simply uses current national currency exchange rates with the dollar to compare one nation with another. It thus fails to capture real purchasing power & inflation. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) measurements of GDP seek to remedy this, and Russia's GDP PPP, not really needing much foreign currency, is far better even compared to Germany than it is to Italy's. Looking at GDP in PPP terms removes price level differences and allows a better comparison, especially of living standards, between countries. In these terms Russia overtook Germany in the summer of 2023 to become the fifth wealthiest economy in the world and the largest in Europe, worth $5.3 trillion.[2]

Russian GDP nominally rose more than any G7 country in 2023. The average Russian household ended the year with about 18% more money in the bank than a year earlier. Sberbank, Russia’s largest state-controlled bank, posted a 5.5-fold year-on-year net profit jump to a record high of 1.5 trillion rubles (USD $16.3 billion). The defense industry employs 3.5 million people and many factories have doubled their workforce since the beginning of the SMO. The economic boom is result of defense stimulus spending, Keynesian economics, a government deficits. Compared to the United States, Russia is a piker in the debt markets. The U.S. gas $35 trillion national debt and growing), nearly a $1 trillion dollar defense budget, does not produce tanks, failed to produce a functional hypersonic missile, incapable of matching Russia’s output of artillery shells, and has become largely a service economy. The United States is no longer an industrial powerhouse.

As trade ties between Russia and the EU were severed, Central Asian EU-trade increased to allow the reexport of EU goods (including dual use) to Russia. Trade with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan increased. The Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) became an effective mechanism for sanctions avoidance.

To give one example, German luxury car export to Kyrgyzstan increased by 31,000%.[3] A major Russian gas deal with Uzbekistan and a $6bn coal deal with Kazakhstan, where almost 50% of foreign companies registered are now Russian, attest to an intensification of ties. Additionally, the multi-modal Middle Corridor was expected to replace the sanctioned Northern Corridor running through Russia. But the Middle Corridor still faces infrastructure bottlenecks and the Northern Corridor now transits pre-war volumes again. Central Asian migrant labor remittances increased, constituting 20% of Uzbek GDP, and higher percentages in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

See also

References

- ↑ https://www.bitchute.com/video/BzSeX5ww7YFy/

- ↑ https://intellinews.com/russia-overtakes-germany-to-become-fifth-biggest-economy-in-the-world-in-gdp-on-a-ppp-basis-286944/?source=russia

- ↑ 31,000% surge in car, ship, toy exports — Europe’s suddenly trading with Central Asia post Russia war, NIKHIL RAMPAL, The Print, 15 December, 2023. theprint.in