Victorian era

The Victorian era was the period in Great Britain under the long-lived Queen Victoria who reigned from 1837 to 1901. The term is also used to describe later nineteenth century western society in general with its strong moral standards and sharply defined gender roles. This era is a mixture of suffocating secularism atop Christian roots.

An age characterized by rapid scientific and technological advance like the steamship, the photography, the electric power supply, and the telegraph; and the rice of population, refined sensibilities and prosperity. Some scholars feel that atheism and disbelief rapidly increased in this period,[1] while pre-Victorian writers such as Jane Austen and, 200 years earlier, Shakespeare, almost never quoted the Bible.

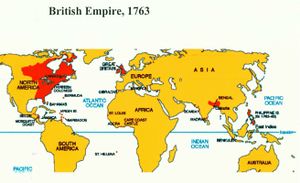

An important aspect of this period is the large-scale expansion of British imperial power (Once a maritime superpower and ruler of half the world). The period saw the rise of a highly idealized notion of what is “English” or what constitutes an “Englishman.” This notion is obviously tied very closely to the period’s models for proper behavior, and is also tied very closely to England’s imperial enterprises. [1]

The (Second) Industrial revolution (between 1840 and 1870) powered Britain to global pre-eminence and initiated social reform. Cotton was one of the driving forces of the Industrial Revolution. [2] Although the steam engine was first invented in 1769 by James Watt, it was in the nineteenth century that the real impact of steam was fully felt. Steam changed everything. New mass communication via the telegraph, newspapers and - from 1876 - the telephone meant that the rate of change accelerated further. [3]

The nineteenth century was a world of free markets, free trade and laissez-faire government, with all moves towards paternalism - in areas such as public health and poor laws - fiercely resisted. It was every man for himself. [4]

People living in Victorian times were resourceful and inventive. Industry was well developed and there was significant input to the infrastructure (including roads, transport systems, drainage and water supplies) of towns and cities. Throughout the Victorian Empire (which included many countries around the world) railways were established, roads and civic buildings constructed, schools and libraries built, and water and sewage services provided to many homes. [5] Between 1840 and 1880 some 15 thousand miles of railways were opened in Britain. [6] The spread of railways stimulated communication. In 1882, Thomas Edison opened the world’s first steam-powered electricity generating station in London.

Victorian era was a tremendously exciting period when many artistic styles, literary schools, as well as, social, political and religious movements flourished. [7] Though the Victorian Era of art began with a return to the classic realism which was popular during the height of ancient Roman and Greek societies, the many technological advances made during that time caused changes in the way scientists, artists and the public viewed art and aesthetics. [8]

Victorian painters include Joseph Mallord William Turner, John William Waterhouse, George Frederick Watts, Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, Lord Leighton, E. J. Poynter, Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Edwin Weeks, Albert Moore and William Stephen Coleman.

The Victorian era was a golden age for sculpture. Among the most important sculptors: John Gibson, Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, Richard C. Belt, Sir Francis Chantrey, George Frampton, Thomas Longmore and John Hénk, Hamo Thornycroft, Thomas Wilkinson Wallis, Alfred Gilbert, and Harry Bates. [9] Sculpture could be found everywhere in Victorian Britain: in galleries, museums, and great exhibitions; in homes, parks, gardens and city squares. [10]

Victorian authors include names like: William Wordsworth, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Robert Louis Stevenson, Alfred Lord Tennyson, William Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell, Lewis Carroll, William Morris, Oscar Wilde, John Ruskin, Thomas Hardy, H. G. Wells, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. [11]

Contents

Morality

The late Victorian social purity movement heralded a new phase in the history of moral regulation, generating significant levels of Anglican and Nonconformist support for male chastity and the elimination of the sexual double standard. Historians have studied the use criminal legislation and censorship to elevate standards of public morality. Morgan (2007) stresses the role of women activists who were prominent campaigners for social purity. Women purity workers exerted enormous pressure on the professional hierarchies of church and chapel, actively reworking Christian readings of the body so as to bring the moral influence of the churches to bear on public opinion. In so doing, they brought about a significant transformation in clerical attitudes that regarded discussions of sex as beyond the boundaries of civilized discourse and led in the promotion of a regulatory, but nonetheless highly public, religious discourse on sexuality. Sue Morgan, "'Wild Oats or Acorns?' Social Purity, Sexual Politics and the Response of the Late-Victorian Church," Journal of Religious History 2007 31(2): 151-168 online at EBSCO.

See also

External links

- Victorian Artists.

- A List of Victorian Writers.

- 8 Great Victorian Novelists.

- Victorian Architecture. Architecture.

- The Art of Sculpture in Victorian Britain. Sculpture.

- What is the Victorian Web?