Harry Truman

| Harry S. Truman | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 33rd President of the United States From: April 12, 1945 – January 20, 1953 | |||

| Vice President | None (1945–1949) Alben Barkley (1949–1953) | ||

| Predecessor | Franklin Roosevelt | ||

| Successor | Dwight Eisenhower | ||

| 34th Vice President of the United States From: January 20, 1945 – April 12, 1945 | |||

| President | Franklin Roosevelt | ||

| Predecessor | Henry Wallace | ||

| Successor | Alben Barkley | ||

| Former U.S. Senator from Missouri From: January 3, 1935 – January 17, 1945 | |||

| Predecessor | Roscoe Patterson | ||

| Successor | Frank Briggs | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Democratic | ||

| Spouse(s) | Bess Wallace Truman | ||

| Religion | Southern Baptist | ||

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884 – December 26, 1972), a liberal Democrat from Missouri, was the president of the United States from 1945–1953, taking over when Franklin D. Roosevelt died in April 1945. He made the decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in order to force Japan's surrender. Angered at the Soviet Union's seizure of Eastern Europe, he moved away from FDR's détente to a policy of containment, reinforced by the Truman Doctrine (1947) to resist Communist subversion, the Marshall Plan (1948–51) to rebuild and modernize western Europe's economies, and the NATO military alliance of 1949. Truman, advised by Dean Acheson and the State Department, set the policies to oppose the Soviet Union as the Cold War began. Truman was the last president who was a college dropout.

Ignoring Asia, he later saw America's close ally China fall to the anti-American Communists under Mao Zedong in 1949; the US and China fought each other to a draw during the undeclared Korean War, 1950–53. Truman fired his top general, Douglas MacArthur, during this conflict and saw his popularity plunge.

As World War II ended, the massive problem of reconverting the 45% of the economy devoted to war production baffled Truman. Listening to liberal advisers, he refused to end extremely unpopular price controls, and was unable to stop a massive wave of strikes in major industries in 1945–46. Voter dissatisfaction lead to the Republican capture of Congress in 1946; with Senator Robert A. Taft as the conservative Republican spokesman, Congress repealed many of the wartime restrictions on business and lowered taxes. Taft rewrote the labor laws in the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, balancing the rights of unions, management and the public interest; it became law over Truman's signature and remains in effect.

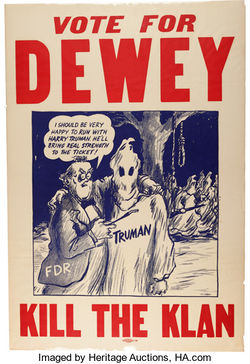

Truman began with very high popularity ratings, but they plunged to the lowest on record. Democrats were unable to stop his renomination in 1948, but the far left nominated FDR's vice president Henry A. Wallace, and Southern Democrats nominated Dixiecrat J. Strom Thurmond. Observers almost unanimously expected victory for the Republican candidate, Governor Thomas E. Dewey, a liberal from New York. Total astonishment greeted Truman's stunning election victory, as he reassembled the New Deal Coalition for the fifth consecutive victory, pulling in on his coattails a Democratic Congress.

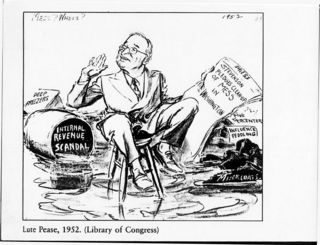

Although the Democrats organized Congress in 1949, the Conservative Coalition of Northern Republicans and Southern Democrats was in control, and Truman was unable to pass much of his liberal Fair Deal program. Nevertheless, he pursued civil rights through executive orders, especially a 1948 order to end racial discrimination in the military. Blacks no longer remained in segregated units and were to receive equal treatment.[1] Truman's failures to deal with "Korea, Communism and Corruption" forced him to withdraw from reelection in 1952 and gave the Republicans an opportunity to crusade against him and elect Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952.

Despite his common reputation as a hero for civil rights due to his FEPC efforts, Truman was a lifelong entrenched racist known for anti-black remarks even in his later years, in addition to ties with notorious Mississippi demagogue Theodore Bilbo during the 1930s, as well as deceptively participating in a political maneuver which killed the Anti-Lynching Bill of 1935 (see below).

Overshadowed at first by his predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Truman established a reputation as a blunt, unsophisticated fighter for the common man, who took responsibility for his actions because, he said, "the buck stops here." His stunning reelection victory in 1948 baffled the experts and has inspired underdogs ever since. He is more popular in the present day than he was when he left office. His policy positions make him an icon for liberals.

Contents

- 1 Early life

- 2 Pendergast machine

- 3 Senate

- 4 Presidency

- 5 Domestic affairs

- 6 1948 election

- 7 Second term: Fair Deal

- 8 National security

- 9 Korean War

- 10 Retirement

- 11 Evaluations

- 12 Quotes

- 13 See also

- 14 Further reading: basic books and articles

- 15 Advanced bibliography

- 16 Historiography

- 17 References

- 18 External links

Early life

Truman was born on a farm near Lamar, in western Missouri, and grew up on a farm near Independence, Missouri. His grandparents had been Confederate sympathizers who had been rounded up by the Union army in the Civil War.[2] After graduating from high school in Independence, with good skills in history and music, he enrolled in a local business college in Kansas City, Spalding's Commercial College, but dropped out and instead become a bank clerk in Kansas City.

Always a joiner, he was active in the Missouri National Guard. From 1906 to 1917 he managed his father's 600-acre farm at Grandview, Missouri. During World War I his National Guard regiment was mobilized in 1917, he entered the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, sailing for France in 1917 as a lieutenant. Truman was soon promoted to captain in Battery D, 129 Field Artillery Battalion, 35th Division, A.E.F., and returned to the United States a major in 1919, after combat at St. Mihiel and in the Argonne offensive. He was in an artillery unit, and learned about gas warfare; he was never wounded, He married Elizabeth "Bess" Wallace on June 28, 1919; they had one daughter, Margaret, who married a New York Times editor. With an army buddy he invested his savings in a Kansas City haberdashery, but this venture was a failure.

Pendergast machine

Discouraged by his lack of business success and without funds, Truman sought the help of friends. His farm background, his war record, his Masonic connections, his Baptist Church affiliations, and his genial personality recommended him to Thomas J. Pendergast, the Democratic political boss of Kansas City and much of western Missouri. Pendergast, an Irish Catholic, had a strong base among the Irish Catholics and used Truman to reach out to Protestants, farmers and veterans. He made Truman the overseer of highways for Jackson County. Truman biographer David McCullough recounts:

| “ | That gambling, prostitution, bootlegging, the sale of narcotics and racketeering were a roaring buisiness in Kansas City was all too obvious. Nor did anyone for a moment doubt that the ruling spirit behind it all remained Tom Pendergast. It was the Pendergast heyday.[3] | ” |

In 1922 Truman was elected a county judge; needing some legal knowledge he studied nights for two years at Kansas City Law School; it was his only education beyond high school, although he read history. In the 1924 GOP landslide he was defeated for reelection, but in 1926 he was returned to office as presiding judge of the court, the duties of which also involved administrative supervision of many county expenditures, including $60 million for public works; Truman put only Democrats from the Pendergast machine on the county payroll.[4] In 1924, Truman paid $10 (equivalent to more than $120 today) as a membership fee to join the Ku Klux Klan, but withdrew when he learned that Pendergast, a Catholic, would not support anyone who belonged to an anti-Catholic organization;[5] the Klan then campaigned against Truman.

In 1933, with one call to Washington, Pendergast got the director of the federal reemployment service in Missouri fired, and his job given to Truman.[6] In 1934, Pendergast tapped Truman to run for Senate. In the 1995 biopic Truman, writer Thomas Rickman portrays the dialogue:

| “ | Boss Tom Pendergast: I've got a job for you.

Harry S. Truman: Well, that's mighty nice of you. What's the job, dog-catcher? Boss Tom Pendergast: How would you like to run for Congress? Harry S. Truman: Well, Jesus Christ and General Jackson. The answer's yes.[7] |

” |

Senate

In 1934 Pendergast arranged for Truman's nomination as United States Senator on the Democratic ticket; he was elected in the democratic landslide as a supporter of Roosevelt and the New deal. His first term in office was uneventful, except for a failed effort to prevent the renomination of Maurice Milligan for U.S. District Attorney for the Western District of Missouri; Milligan had obtained the conviction of 35 Pendergast "ward leaders" for vote frauds.

Civil rights record

In 1935, the United States Senate was deadlocked over the Costigan–Wagner Act; Democratic Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson forced an adjourn motion in late April which failed very narrowly, though political trading brought another motion to pass on May 1; Truman was among the votes which switched into supporting adjourning the chamber, which all but killed the Act from passing.[8]

World War II

He was re-elected in 1940 after a terrific battle against Lloyd Stark, Truman became nationally infamous as chairman of the "Truman Committee". Ostensibly for the purpose of investigating waste, fraud and inefficiency in government contracts, the committee allowed Truman and his associates to interfere in many aspects of Executive policy on the prosecution of the war. The committee frequently tampered with or even canceled contracts with legitimate suppliers of essential war materials when they would not deal with Truman's Kansas City patrons, the Pendergasts. Its formal name was the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program. Nevertheless, he was an energetic and forthright supporter of the New Deal and won widespread party favor for his attacks on business malfeasance in war production. He forced changes in the aircraft and ship construction programs, and worked well with other border state Democrats, especially Alben Barkley of Kentucky, the Majority Leader.

FDR picks a new vice president

In 1944, after Vice-President Henry A. Wallace had been rejected by leading Democrats as too far to the left, Truman supported his friend former senator James F. Byrnes of South Carolina for that office. Catholics vetoed Byrnes, who had left that faith. Truman himself became Roosevelt's choice as a compromise vice presidential candidate, and the two were elected.

Roosevelt had been in ill-health since his return from the Teheran conference. At the 1944 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, DNC Chairman Bob Hannegan went for instructions to President Roosevelt's private railway car just before the July convention officially began. Roosevelt had decided to dump incumbent Vice-President Henry Wallace. Worried over dissension on the choice of a successor, Roosevelt told Hannegan: "Go on down there and nominate Truman before there's any more trouble. And clear everything with Sidney." [9] The President could not make the selection of Truman until Sidney Hillman,[10] Director of the Political Action Committee for the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) approved it.[11] When Harry Truman walked into the smoke-filled room [12] of DNC at headquarters at the Stevens Hotel in Chicago, Soviet spies John Abt, Lee Pressman, and Nathan Witt, were on hand."[13]

Presidency

Roosevelt ignored Truman between the election in November 1944 and the inauguration in January; even as Vice president Truman was not consulted on national policies, and not informed of major decisions, nor of the atomic bomb. Although he realized Roosevelt's health was failing rapidly, he made no preparations for assuming the presidency and did not even build up a staff of advisors. Truman succeeded to the Presidency upon the death of FDR on April 12, 1945.

President Truman pledged that in office he would carry on the liberal domestic policies of Roosevelt. He distrusted most of FDR's cabinet and set about to assemble his own team.

Winning World War II

During his term as President, he presided over the conclusion of World War II in both Europe and Japan. On April 25 his telephoned speech opened the San Francisco Conference establishing the United Nations. A week later Germany surrendered, and from July 17 to August 2, 1945, Truman attended the Potsdam Conference with Britain's Winston Churchill (soon replaced by the new prime minister Clement Attlee) and Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union.

Atomic bomb

The alternative Truman faced was to order use of the atomic bomb which might shock the Japanese into surrender, or order the planned invasion of Japan's home islands; casualty estimates for Americans ranged very widely. Casualty estimates for Japan ranged into the millions. Secretary of War Henry Stimson made the real decision: to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan immediately surrendered on terms that allowed Emperor Hirohito to stay on the throne and not be tried as a war criminal. Truman put General Douglas MacArthur in charge of occupying and controlling Japan; MacArthur remained in charge until the peace treaty was finally signed in 1951.

Truman kept control of the bomb in civilian hands—the Air Force and State Department did not even know how many bombs existed until 1948, when only eight had been built. The postwar military strategy was not built around nuclear weapons.

Debating the decision

Conservatives and liberals

In general, conservatives and liberals alike have applauded and supported the a-bomb decision because it shortened the war, and prevented hundreds of thousands or millions of casualties. The New Left or "revisionist" interpretation argues that the bomb was not necessary to end the war and that no invasion was necessary. They have no evidence to support that argument. They do have fragments of evidence that give weak support to the argument that one American goal was to intimidate the Soviet Union. The revisionists believe the US should have stayed friends with the Soviets, and that Truman was guilty of starting the Cold War (which they consider a bad thing). Morally the revisionists assume the USA was no better or worse than the Soviets—admitting to Soviet atrocities, they argue that socialism was morally superior to capitalism, which itself was a great evil the US intended to spread. In terms of the bomb, Secretary of State James Byrnes did make some offhand references to influencing Moscow, but his comments did not reflect the policy of the State Department or White House, and certainly not those of Stimson, who was by far the most important decision-maker. Vice President Truman had been kept uninformed about the atomic bomb; he had little interest in military affairs and his chief military aide, General Harry Vaughan, was a drinking buddy likewise unfamiliar with what was happening in the war. Truman, therefore, relied entirely on his Secretary of War, Henry Stimson. At Potsdam he approved the atomic bomb targets selected by Stimson and, on the way home, he authorized the bombing of Hiroshima, Japan, August 6, 1945, and Nagasaki three days later.

How the decision was made

The decision to drop the atomic bomb has been the focus of one of the most heated debates among both scholars and the public since 1945. After 1945 the debate was dominated by "traditionalist" scholars, who argued that the U.S. had no choice but to drop the bomb as a way to bring World War II to an end. The traditionalists were succeeded in the 1960s by "revisionists," who asserted that the dropping of the bomb was done to intimidate Stalin, not end the war. The leading revisionist historians emerged from the "New Left" movement of the 1960s and rejected any notion of the moral superiority of America or capitalism to the Soviet Union. They thought the Cold War and containment were poor policies and generally favored détente, along the lines proposed by Henry Wallace. They include Gar Alperovitz, Barton J. Bernstein, Kai Bird, Diane Shaver Clemens, Bruce Cumings, Richard Freeland, Lloyd Gardner, Gabriel Kolko, Walter LaFeber, Thomas Paterson, Harvard Sitkoff, Ronald Steel, Athan Theoharis, and William A. Williams (the leader of the "Wisconsin School"). The revisionists are not monolithic, but they usually agree that Truman and his advisers were wrong whether the issue is the Cold War, Korea, or the atomic bomb. Revisionists had argued that Truman's goal at Potsdam was to prevent Soviet entry into the war against Japan, and the atomic bomb was used to scare them off. However, in 1983 archivists discovered a letter Truman wrote to his wife from Potsdam on July 18, 1945: "I've gotten what I came for—Stalin goes to war August 15 with no strings on it . . . I'll say that we'll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids who won't be killed! That's the important thing."[14]

In the 1990s, a more nuanced historical approach emerged searching for a middle ground, offering a number of more credible studies, essentially arguing that neither the traditional nor the revisionist interpretations were entirely satisfactory.[15]

Domestic affairs

Reconversion of the economy to peacetime

The process of reconversion to peacetime was rocky. It was impossible to bring soldiers home fast enough, and they and their families protected loudly. All war contract were canceled, shutting down munitions plants and throwing millions of workers (many of them women) out of jobs, just as the 12 million service members were coming home. Truman sought to retain price controls against the vehement opposition of business but yielded somewhat in the face of bitter popular opposition. Large-scale strikes disrupted the economy, especially a coal miners strike and a threatened nationwide strike by railroad workers. He threatened to draft the railroad workers and the strike was called off; unions began to oppose him but he regained union support by his later attempts to veto or repeal the Taft-Hartley labor relations law. Truman's opposition to tax cuts, his insistence on price controls, and his lack of aggressive support of labor programs weakened his party. To voters frustrated with shortages and controls, Truman seemed indecisive and inconsistent; his efforts to deal with a postwar wave of strikes managed to alienate both organized labor and those who wanted more restraints on unions. Voters who normally supported liberal and labor candidates stayed home, resulting in a Republican landslide in 1946, giving the GOP a majority in both houses of Congress. Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft became the main GOP spokesman in Congress, tangling often with Truman.

Moving left

Gradually Truman created his own administration, using the Fair Deal label to express its goals in domestic affairs. Truman systematically removed the Roosevelt cabinet and inner circle of advisers. The most dramatic episode was firing Henry A. Wallace in 1946 because of his outspoken criticism of the administration's foreign policy as too harsh on the Soviet Union. Liberals saw themselves in a struggle with conservatives for Truman's soul after the 1946 election. Linked to the President through top aide Clark Clifford, these liberals included Oscar Ewing, former party official and director of the Federal Security Agency, Leon Keyserling, member of the President's Council of Economic Advisers, and David Morse, assistant secretary of labor. They embraced the memo plotting 1948 campaign strategy written by former Roosevelt adviser James Rowe, which urged Truman to "move to the left and focus on building a coalition of groups that centered on organized labor, liberals, and northern urban African Americans."[16] Liberals had national support from the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), led by Walter Reuther, Eleanor Roosevelt, Joseph Rauh, James Rowe, Reinhold Niebuhr, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Hubert Humphrey, and Ronald Reagan.[17] The ADA was hostile to the Soviet Union, battled American Communists and fellow travelers like Wallace, and supported the purge of Communists from the CIO labor unions. Truman agreed with the ADA and moved left after 1946.[18]

However he could not tolerate Henry A. Wallace and the far left, which had considerable Communist support. When Wallace, then Secretary of Commerce, in 1946 denounced Truman's tough stand against Stalin, Truman fired Wallace.

In 1947 Truman asked Congress for stand-by price controls, rationing, and bank and consumer credit control as parts of an anti-inflation program, but his ideas were ignored by the Republicans who controlled Congress.Shift in public image on civil rights

Disgusted by violence against black veterans in the deep South, Truman called for the extension of the wartime Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) program that called for fair employment practices, but Congress refused and it ended. He created the Presidential Commission on Civil Rights in 1946 by executive order (with no congressional approval needed); it recommended desegregation of local public facilities and the removal of restrictive covenants that prevented blacks and Jews from purchasing houses in restricted neighborhoods. The Commission generated attention but no action.[19] Indeed, Congress refused to pass any civil rights legislation before 1957. Truman therefore decided to use his executive powers, and focused on guaranteeing equal opportunity in the military and the civil service.

The Army and Navy operated segregated units, and refused to be part of a "social experiment" in integration.[20] The Air Force, however, was much more willing. Between 1941 and 1951 it went from a segregated force to the first truly integrated service. Key generals became convinced that segregation was a drag on efficiency, and the Air Force decided to integrate in April 1948. before Truman issued his famous Executive Order 9981 on July 26, 1948, calling for equal opportunity in all the armed services. It allowed segregation but called for "equality of treatment and opportunity." In the face of opposition from some high-ranking officers, the Air Force moved cautiously, but by 1951 the last black unit was dissolved and the Air Force was completely integrated.[21] Order 9981 created the Fahy Committee to implement the new policy. Truman's order did not actually integrate the Army—it used segregated units during the Korean War—but it opened the way for integration in the early 1950s.[22] Public opinion was generally favorable except in the deep South (which voted against Truman in 1948).

1948 election

As the presidential election of 1948 approached, no one thought Truman could be reelected. Truman's policies had alienated left right and center, but the party had no real alternative. Neither Roosevelt nor Truman had groomed a likely successor. Party leaders considered asking Dwight D. Eisenhower to run, but he refused. Liberals led by Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota inserted a strong civil rights plank in the platform, causing a walkout of the deep South. Truman was renominated by default, with Barkley as the vice-presidential candidate. Truman thrilled the convention by announcing his plan to call the Republican-controlled Congress back into special session to "ask them to pass the laws to halt rising prices, to meet the housing crisis--which they say they are for in their platform." When this special session accomplished little, as Truman expected, it gave the president a chance to attack the "Do Nothing" Congress.

Both the left and right wings of the party split off and ran their own candidates. Henry Wallace, the candidate of the Progressive Party, was expected to divert labor, leftist and black votes, while J. Strom Thurmond was the "Dixiecrat" candidate whose supporters controlled the Democratic party in Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina.[23] Truman exploited his multiple opponents, driving a wedge between the liberals and the Communists who controlled the Wallace movement, and holding the line in the outer South. Most of all he exploited the difference between the conservative Republicans who controlled Congress, and the liberal Republican candidate Tom Dewey. Truman crusaded against the Republicans as evil rich men, blasting them as fascists and denouncing the 80th Congress for its failure to help the average citizen.[24] "Give 'em hell" fury delivered in 275 speeches over 21,928 train-miles had more impact that Truman's promises of more money for federal housing, higher social security and unemployment benefits, free medical care for everyone, the continued subsidy of farm prices, and a fair deal for minorities. The pollsters misjudged the election, as did all the traditional pundits. Truman rallied enough of the New Deal Coalition to win by 2.2 million votes, and carry in a Democratic Congress on his coattails. The key farm states of the farm states of Iowa, Wisconsin, and Ohio that Dewey had carried in 1944 now switched to Truman, giving a solid victory in the electoral college of 303 for Truman, 189 for Dewey, 39 for Thurmond, and none for Wallace.[25]

Second term: Fair Deal

During Truman's second term as president, he pressed for civil rights legislation, compulsory national health insurance, and other domestic measures that he called his "Fair Deal" program. Almost nothing was passed by Congress, which was controlled by the Conservative Coalition. His seizure of the steel industry to prevent a strike was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

In foreign affairs, Truman brought in Dean Acheson as Secretary of State, and promoted the Point Four program of aid to underdeveloped countries. The policy of containing Communism was set into operation by the 1949 creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to oversee the integration of the military forces of its member nations in Western Europe and North America. A further step was taken in 1951 with the establishment of the Mutual Security Agency to coordinate U.S. economic, technical and military aid abroad.

Agriculture

Truman won the farm vote in 1948 by charging the GOP shoved "a pitchfork in the farmer's back", but was unable to get new farm programs passed. His second secretary of agriculture, Charles F. Brannan promoted the Brannan Plan, intended to bring widespread changes to farm policy. Brannan proposed to replace market price supports with direct income payments to farmers. His plan set ceilings on the amount a farmer could receive and limited the program to farmers who did not exceed a set production mark. The Brannan Plan was supposed to foster the "family-sized farm" while providing affordable food for consumers. While Brannan could count on support from the left, especially the National Farmers Union (which was small), labor unions (which were powerful), and consumer groups (which were weak), he was opposed by leading farm economists and the national Farm Bureau (which was large) and the national Chamber of Commerce (representing business). The head of the Farm Bureau decried the plan as intrusive, a form of "creeping socialism," and expensive. The Farm Bureau, dominated by conservatives, resisted any curbs on full agricultural production. A bloc of Midwestern Republican and southern Democratic congressmen opposed replacing market mechanisms with outright government payments to farmers and setting limits on supports to individual farms. The Brannan Plan went nowhere and instead, the conservative farm bloc passed the Agricultural Act of 1949 with high price supports.[26]

Brannan justified his plan of direct assistance to small farmers, by reasserting the importance of the small family farmer as the foundation of American democracy. However, in the Grange small farmers opposed the plan because it too closely resembled welfare and would undermine their self-image as independent yeomen and successful entrepreneurs. Brannan sought to protect the small farmer against competition from the large companies, but the plan was not accepted by Congress because farmers self-image would not allow for welfare.[27]

National security

Truman Doctrine and origins of Cold War

In early 1947 the British government, which was socialist but anti-Communist, secretly told Washington its treasury was empty and it could no longer give military and economic aid to Greece or Turkey, requested the U.S. take over. Acheson convinced Truman to act quickly lest Greece be taken over by its communist partisans who were at the time strongly supported by the Soviet government working through the communist Bulgarian and Yugoslav governments. If Greece fell, Turkey would be helpless and soon the eastern Mediterranean would fall under Stalin's control. In a dramatic message to Congress on March 12, 1947, President Truman said that the U. S. must take immediate and resolute action to support Greece and Turkey.[28] The Republican Congress, after extensive hearings, approved this historic change in U. S. foreign policy in a bill signed May 22, 1947. Thus was born the “Truman Doctrine.” Greece suppressed the insurgents; both Greece and Turkey joined NATO.[29]

Recognition of Israel

Truman usually followed the advice of the State Department in national security matters, largely ignoring the Pentagon and Congress. In the case of recognition of the independent state of Israel in 1948, however, he overruled the urgent pleas of the State Department and immediately recognized Israel. State had warned that recognition would anger the Arabs in the Middle East; Truman, however, was more responsive to domestic politics, where support for Israel was widespread.[30][31]Religion

Truman, a Southern Baptist, sought religious allies in the Cold War. He tried to unite the world's religions in a spiritual crusade against communism, sending his personal representative to Pope Pius XII to coordinate not only with the Vatican but also with the heads of the Anglican, Lutheran, and Greek Orthodox churches. "If I can mobilize the people who believe in a moral world against the Bolshevik materialists," Truman wrote in 1947, "we can win this fight." Since the Roman Catholic Church was his strongest religious ally in the moral battle against international communism, Truman put Rome first in his global strategy, even trying to confer formal diplomatic recognition on the Vatican. At home, he received solid support from Catholics, who were a major element of the New Deal Coalition, but overwhelming resistance from Protestants, especially Southern Baptists who rejected anything "popish." Truman's political-diplomatic effort to formalize a public, faith-driven, ecumenical international campaign failed.[32]

Loss of China

Chiang Kai-shek, America's wartime ally and head of the Nationalist forces in China, was caught between two wars—a war on China by Japan and a war with Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communists. The U.S. policy was to avoid a civil war and to threaten to withhold additional aid to the Nationalists unless they worked out a compromise. No compromise was possible, and Truman refused to send in combat troops to fight the civil war. General George Marshall, who spent a year in China as Truman's emissary, testified that combat aid might have prevented a Communist victory, but General David Barr's military mission to China was specifically instructed not to supply this kind of assistance.[33] General Albert C. Wedemeyer recommended this approach in his report on his 1947 fact-finding mission, but Marshall personally suppressed the report.[34] Chiang believed that the Truman Doctrine to contain the spread of International Communism directed from Moscow would be extended to China, and ordered an offensive as soon as word of the new policy reached him.[35]

Dean Rusk, Assistant Secretary of State in charge of the Far Eastern Division, said on May 18, 1951, what the critics had been saying,

| “ | The independence of China is gravely threatened. In the Communist world there is room for only one master. . . . How many Chinese in one community after another are being destroyed because they love China more than they love Soviet Russia? The freedoms of the Chinese people are disappearing. Trial by mob, mass slaughter, banishment to forced labor in Manchuria and Siberia. . . . The peace and security of China are being sacrificed by the ambitions of the Chinese conspiracy. China has been driven by foreign masters into an adventure in foreign aggression. | ” |

Rusk continued,

| “ | We do not recognize the authorities in Peiping for what they pretend to be. It is not the government of China. It does not pass the first test. It is not Chinese. . . . We recognize the Nationalist government of the Republic of China even though the territory under its control is severely restricted.[36]…we believe it more authoritatively represents the views of the great body of the people of China, particularly their demand for independence from foreign control….That government will continue to receive important aid and assistance from the United States. | ” |

Risks in Korea

Conditions inviting the North Korean attack were created by the United Nations which issued a resolution for withdrawal of both Soviet and American troops. Troops began withdrawing September 15, 1948, leaving only about 7500 Americans lightly armed. This left in South Korea 16,000 Koreans and 7500 Americans, both groups lightly armed, against 150,000 fully armed North Korean Communists. General Roberts, head of the U. S. Military Mission said the South Koreans were not permitted to arm adequately. The Korean part of Wedemeyer's report was suppressed. Wedemeyer said:

| “ | American and Soviet forces . . . are approximately equal, less than 50,000 troops each, [but] the Soviet-equipped and trained North Korean People's (Communist) Army of approximately 125,000 is vastly superior to the United States-organized constabulary of 16,000 Koreans equipped with Japanese small arms. The North Korean People's Army constitutes a potential military threat to South Korea, since there is strong possibility that the Soviets will withdraw their occupation forces and thus induce our own withdrawal."[37] | ” |

Wedemeyer warned that this would take place as soon as "they can be sure that the North Korean puppet government and its armed forces . . . are strong enough . . . to be relied upon to carry out Soviet objectives without the actual presence of Soviet troops."

Communists inside US

The bipartisan statutory Moynihan Secrecy Commission concluded, "President Truman was almost willfully obtuse as regards American Communism." [38]

Foreign policy: détente to containment

Truman had no knowledge or interest in foreign policy before becoming president, and depended on the State Department for foreign policy advice.[39] Truman shifted from FDR's détente to containment as soon as Dean Acheson convinced him the Soviet Union was a long-term threat to American interests. They viewed communism as a secular, millennial religion that informed the Kremlin's worldview and actions and made it the chief threat to American security, liberty, and world peace. They rejected the moral equivalence of democratic and Communist governments and concluded that until the regime in Moscow changed only American and Allied strength could curb the Soviets. Following Acheson's advice, Truman in 1947 announced the Truman Doctrine of containing Communist expansion by furnishing military and economic American aid to Europe and Asia, and particularly to Greece and Turkey. He followed up with the Marshall Plan, which was enacted into law as the European Recovery Program (ERP) and led ultimately to NATO, the North Atlantic Alliance for military defense, signed in 1949. On May 14, 1948, Truman announced recognition of the new state of Israel, making the United States the first major power to do so.

Korean War

The Korean War began at the end of June 1950 when North Korea, a Communist country, invaded South Korea, which was under U.S. protection. Without consulting Congress Truman ordered General Douglas MacArthur to use all American forces to resist the invasion. Truman then received approval from the United Nations, which the Soviets were boycotting. UN forces managed to cling to a toehold in Korea, as the North Koreans outran their supply system. A counterattack at Inchon destroyed the invasion army, and the UN forces captured most of North Korea on their way to the Yalu River, Korea's northern border with China. Truman defined the war goal as rollback of Communism and reunification of the country under UN auspices.

On January 12, 1950, Secretary of State Dean Acheson gave a speech to the National Press Club excluding South Korea from the defense perimeter, though Truman denies any wrongdoing on his behalf.[40] Omar Bradley blamed Truman and Acheson in his memoir A General's Life, and historian Bill Shinn concurs.[41][42] Acheson apologists cite the fact Stalin and North Korea already had contingency plans for invasion of the South; nonetheless Acheson's speech green-lighted a leftist takeover of a country most Americans never heard of, let alone were able to find on a map.

During his address to the UN General Assembly, Truman said, “The men who laid down their lives for the United Nations in Korea will have a place in our memory, and in the memory of the world, forever. They died in order that the United Nations might live.” [43]Late in 1950 China intervened unexpectedly, drove the UN forces all the way back to South Korea. The fighting stabilized close to the original 38th parallel that had divided North and South. MacArthur wanted to continue the rollback strategy but Truman arrived at a new policy of containment, allowing North Korea to persist. Truman's dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur in April 1951 sparked a violent debate on U.S. Far Eastern policy, as Truman took the blame for a high-cost stalemate with 37,000 Americans killed and over 100,000 wounded.

Truman fired his ineffective defense secretary Louis Johnson, and brought back George Marshall.

NSC-68

The top-secret NSC-68 policy paper was the grounds for escalating the Cold War, especially in terms of spending on rearmament and building the hydrogen bomb. The integration of European defense was given new impetus by continued U.S. support of NATO, under the command of General Eisenhower. Truman committed the US to contain Communist expansion in Vietnam, where the Communists under Ho Chi Minh were trying to overthrow the French colonial regime. The State Department insisted that France give more autonomy to the Vietnamese. The US paid for about 80% of the French war costs. The problem was that the French were more interested in preserving their grandiose empire, and less interested in stopping Communism, while the US opposed colonial empires and saw Communism as the great threat to world peace and stability.

Following NSC-68, Truman's last four budgets saw expenditures on national security quadruple from $13 billion in 1950 to $50 billion in 1953.

1952 election

On the political front, revelation of scandals in the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, in the Bureau of Internal Revenue and even the White House[44] opened the administration to attack.

Truman sought reelection in 1952 despite his dismal showing in the polls. He was defeated in the New Hampshire primary by Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee, and withdrew. Truman supported Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson. Eisenhower won the GOP nomination and crusading against the Truman administration's failures regarding "Korea, Communism and Corruption," was elected in a landslide, ending 20 years of Democratic control of the presidency.

Retirement

Truman returned to his home in Independence, Missouri. He devoted himself to creating the Truman Library there; it was dedicated in July 1957 and is a part of the National Archives. With a staff of assistants, he wrote his memoirs in two well-received volumes, gave many interviews, and intervened occasionally in Democratic national politics on behalf of liberal candidates such as Adlai Stevenson.

He died on December 26, 1972.

Evaluations

Already by the 1960s, Truman had become a hero to liberals and Democrats, nostalgic over the successes of the New Deal Coalition that sputtered and collapsed in the 1960s. Even Republicans came to forget the nasty days and celebrated Truman as the hero of the underdogs and the man who rebuilt Europe through the Marshall Plan and stood up to Communism through NATO.

Truman's reputation among scholars has gone from very low when he left office, to high after 1990. He is now widely considered to have been a tough-minded, decisive, and effective leader who ably guided the nation through the perilous waters of the early Cold War and whose policy of containment essentially laid the foundations for American "victory" in that prolonged conflict in 1989. For many historians, the down-to-earth Midwesterner now merits consideration as one of the greatest American presidents. In recent years presidential aspirants of both parties have claimed Truman as their own, especially if their election chances seem as hopeless as Truman's did in 1948. His reputation has been bolstered by scholarly biographies by Ferrell (1994), Hamby (1995), and especially McCullough's Pulitzer prize-winning popular biography (1992). The in-depth analysis by Leffler (1992), cautiously praised the Truman administration's essential wisdom in handling a myriad of problems.

While Truman's public image was headed up, his reputation among scholars declined in the 1970s. Kirkendall concluded in 1974 that negative appraisals of Truman and his administration "may in fact have become the dominant interpretation, at least among the younger scholars."[45] In terms of foreign policy a strong negative view comes from Offner (2002) who argues that Truman was a "parochial nationalist" whose "uncritical belief in the superiority of American values and political-economic interests," conviction that "the Soviet Union and Communism were the root cause of international strife," and "inability to comprehend Asian politics and nationalism" intensified the postwar conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, precipitated the division of Europe, and set Sino-American relations on a path of long-term animosity. Rather than being a great statesman who carefully weighed various policy alternatives, Offner asserts that Truman's myopia "created a rigid framework in which the United States waged long-term, extremely costly global cold war". As his title suggests, the Cold War was at best a Pyrrhic victory for the United States.[46]

Truman became the model of the underdog who fights back and wins when the experts unanimously predict defeat. Gerald Ford, who had bitterly denounced Truman as a young Congressman proudly proclaimed the Missourian as his hero and conspicuously displayed a bust of Truman in the oval office after Ford became president in 1974. In the 1976 campaign both Ford and his Democratic rival, Jimmy Carter, outdid one another in claiming to be cast from the Truman mold. By 1980 when the Gallup Poll asked "Of all the Presidents we've ever had, who do you wish were President?", Harry Truman finished an impressive third behind Kennedy and FDR.

Quotes

- "No man should be allowed to be President who does not understand hogs."[47]

- "This is a Christian Nation. More than a half century ago that declaration was written into the decrees of the highest court in this land."[48]

See also

Further reading: basic books and articles

- Burnes, Brian. Harry S. Truman: His Life and Times (2003), popular biography excerpt and text search

- Dallek, Robert. Harry Truman (2008) short, popular biography by scholar. excerpt and text search

- Donovan, Robert J. Conflict and Crisis: The Presidency of Harry S. Truman, 1945-1948 (1977); Tumultuous Years: 1949-1953 (1982) detailed 2-vol political history by well-informed journalist; well balanced

- Fleming, Thomas J. Harry S. Truman, President (1993) for middle school audience.

- Graff, Henry F., ed. The Presidents: A Reference History. 2nd ed. 1996, 443–458. ISBN 0-684-80471-9; by leading scholar

- Hamby, Alonzo L. Man of the People: A Life of Harry S. Truman (1995), the best scholarly biography; written by conservative historian who likes HST

- Hamby, Alonzo L. "An American Democrat: A Reevaluation of the Personality of Harry S. Truman," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 1 (Spring, 1991), pp. 33–55 in JSTOR

- Hamby, Alonzo L. "Truman, Harry S."; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000 by a leading conservative historian

- Kirkendall, Richard S. Harry S. Truman Encyclopedia (1990), very useful articles on people, events and policies in HST's career

- Kirkendall Richard S. "Harry S Truman a Missouri Farmer in the Golden Age," Agricultural History, Vol. 48, No. 4 (Oct., 1974), pp. 467–483 in JSTOR

- McCullough, David. Truman. (1993), 1120 pp ISBN 0-671-86920-5 best-selling biography; moderate in tone; Pulitzer Prize excerpt and text search

- McCullough, David. Harry S. Truman, short essay online edition

- Offner, Arnold A. Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War. (2002) 640pp, New Left and hostile to HST; excerpts and text search

- American Experience: Truman (2006), from PBS

- "Classic President Harry S Truman Films: 1945-1965 (2006) 40 newsreels, 101 minutes

Advanced bibliography

These are secondary sources by scholars; unless noted they are generally liberal and supportive of Truman.

Biographies

- Burnes, Brian. Harry S. Truman: His Life and Times (2003); popular biography; excerpt and text search

- Cochran, Bert. Harry S. Truman and the Crisis Presidency , 432 pages; portrays a cynical courthouse politician

- Donovan, Robert J. Conflict and Crisis: The Presidency of Harry S. Truman, 1945-1948 (1977); Tumultuous Years: 1949-1953 (1982), good, detailed 2-vol political history by well-informed journalist

- Ferrell, Robert H. Harry S. Truman: A Life (1994), brief overview

- Fleming, Thomas J. Harry S. Truman, President (1993) for middle school audience.

- Gosnell, Harold Foote. Truman's Crises: A Political Biography of Harry S. Truman (1980)

- Graff, Henry F., ed. The Presidents: A Reference History. 2nd ed. 1996, 443–458. ISBN 0-684-80471-9

- Hamby, Alonzo L. Man of the People: A Life of Harry S. Truman (1995), very well received scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- Hamby, Alonzo L. "The Liberals, Truman, and the FDR as Symbol and Myth," Journal of American History, Vol. 56, No. 4 (Mar., 1970), pp. 859–867 in JSTOR

- Hamby, Alonzo L. "Truman, Harry S."; American National Biography Online Feb. 2000

- Kirkendall, Richard S. Harry S. Truman Encyclopedia (1990)

- McCullough, David. Truman. . ISBN 0-671-86920-5 best-selling biography; Pulitzer Prize excerpt and text search

- Miller, Richard Lawrence. Truman: The Rise to Power (2002), critical evaluation emphasizing corruption of Pendergast machine

Foreign policy

- Appleman, Roy E. South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (June–November 1950) (United States Army in the Korean War) (1960); official U.S. Army history, online version

- Beisner, Robert L. Dean Acheson: A Life in the Cold War (2006), 800pp; a standard scholarly biography; covers 1945-53 only

- Benson, Michael T. Harry S. Truman and the Founding of Israel (1997) online edition

- Berger, Henry. "Bipartisanship, Senator Taft, and the Truman Administration," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 90, No. 2 (Summer, 1975), pp. 221–237 in JSTOR

- Bernstein Barton J. "Roosevelt, Truman, and the Atomic Bomb, 1941-1945: A Reinterpretation," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 90, No. 1 (Spring, 1975), pp. 23–69 in JSTOR, influential New left essay

- Blair, Clay The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950-1953, Naval Institute Press (2003) revisionist study that attacks Truman and top Army leaders for near-criminal incompetence

- Divine, Robert A. "The Cold War and the Election of 1948," The Journal of American History, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jun., 1972), pp. 90–110 in JSTOR

- Frazier, Robert. "Acheson and the Formulation of the Truman Doctrine" Journal of Modern Greek Studies 17#2 (1999), pp. 229–251 online at Project Muse

- Gaddis, John Lewis. "Reconsiderations: Was the Truman Doctrine a Real Turning Point?" Foreign Affairs 1974 52(2): 386–402. ISSN 0015-7120

- Giangreco, D. M. "'A Score of Bloody Okinawas and Iwo Jimas': President Truman and Casualty Estimates for the Invasion of Japan," Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 72, No. 1 (Feb., 2003), pp. 93–132 in JSTOR shows Truman was indeed by very high invasion casualties

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. (2005). 382 pp. excerpt and text search

- Hogan, Michael J. A Cross of Iron: Harry S. Truman and the Origins of the National Security State, 1945-1954 (2000) excerpt and text search

- Ivie, Robert L. "Fire, Flood, and Red Fever: Motivating Metaphors of Global Emergency in the Truman Doctrine Speech." Presidential Studies Quarterly 1999 29(3): 570–591. ISSN 0360-4918 online edition

- Lacey, Michael J. ed. The Truman Presidency (1989), major essays by scholars

- Matray, James I. "Truman's Plan for Victory: National Self-Determination and the Thirty-Eighth Parallel Decision in Korea," Journal of American History, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Sep., 1979), pp. 314–333 in JSTOR Truman planned rollback of Communism in North Korea

- Merrill, Dennis. "The Truman Doctrine: Containing Communism and Modernity" Presidential Studies Quarterly 2006 36(1): 27–37. ISSN 0360-4918

- Offner, Arnold A. "'Another Such Victory': President Truman, American Foreign Policy, and the Cold War." Diplomatic History 1999 23(2): 127–155. ISSN 0145-2096

- Ojserkis, Raymond P. Beginnings of the Cold War Arms Race: The Truman Administration and the U.S. Arms Build-Up (2003) online edition

- Pelz, Stephen. "When the Kitchen Gets Hot, Pass the Buck: Truman and Korea in 1950," Reviews in American History 6 (December 1978), 548–55. Online at Project MUSE

- Pierpaoli, Paul G. Jr.; Truman and Korea: The Political Culture of the Early Cold War. University of Missouri Press, 1999 online edition

- Radosh, Ronald, and Allis Radosh. A Safe Haven: Harry S. Truman and the Founding of Israel (2009), 448pp; by conservative scholars

- Smith, Geoffrey S. "'Harry, We Hardly Know You': Revisionism, Politics and Diplomacy, 1945-1954," American Political Science Review 70 (June 1976), 560–82. in JSTOR

- Spalding, Elizabeth Edwards. The First Cold Warrior: Harry Truman, Containment, And the Remaking of Liberal Internationalism (2006) excerpt and text search

- Wainstock, Dennis D. Truman, MacArthur, and the Korean War (1999) online edition

- Walker, J. Samuel. Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against Japan (1997) online complete edition; excerpt and text search

- Walker, J. Samuel. "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground" Diplomatic History April 2005 - Vol. 29 Issue 2 pp 311–334 fulltext in EBSCO

Domestic policy and politics

- Bernstein Barton J. "The Truman Administration and the Steel Strike of 1946," Journal of American History, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Mar., 1966), pp. 791–803 in JSTOR

- Billington, Monroe. "Civil Rights, President Truman and the South," Journal of Negro History, Vol. 58, No. 2 (Apr., 1973), pp. 127–139 in JSTOR

- Dean, Virgil W. "Charles F. Brannan and the Rise and Fall of Truman's 'Fair Deal' for Farmers." Agricultural History 1995 69(1): 28–53. Issn: 0002-1482

- Dean, Virgil W. An Opportunity Lost: The Truman Administration and the Farm Policy Debate. 2006. 275 pp. excerpt and text search

- Derickson, Alan. "'Take Health from the List of Luxuries': Labor and the Right to Health Care, 1915-1949." Labor History 2000 41(2): 171–187. Issn: 0023-656x Fulltext: in Taylor and Francis, Swetswise, Ingenta, and Ebsco

- Donaldson, Gary A. Truman Defeats Dewey (1998)

- Farhang, Sean, and Ira Katznelson. "The Southern Imposition: Congress and Labor in the New Deal and Fair Deal," Studies in American Political Development (2005), 19: 1-30; online edition

- Freeland, Richard M. The Truman Doctrine and the Origins of McCarthyism: Foreign Policy, Domestic Policy, and Internal Security, 1946-48 (1989), revisionist; New left attack on Truman for being too anti-Communist

- Fried, Richard M. Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective. 1990. online complete edition; excerpt and text search

- Gardner, Michael R. Harry Truman and Civil Rights: Moral Courage and Political Risks. (2002) 296 pp.online edition

- Hamby, Alonzo. Beyond the New Deal: Harry S. Truman and American Liberalism (1973), the most sophisticated biography; by a prominent conservative historian

- Hartmann, Susan M. Truman and the 80th Congress (1971) online edition

- Heller, Francis H. Economics and the Truman Administration (1982) excerpt and text search

- Karabell, Zachary. The Last Campaign: How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election (2001) excerpt and text search

- Koenig, Louis W. The Truman Administration: Its Principles and Practice (1956) online edition

- Komarek de Luna, Phyllis. Public versus Private Power during the Truman Administration: A Study of Fair Deal Liberalism. Peter Lang, 1997. 253 pp.

- Lacey, Michael J. ed. The Truman Presidency (1989), major essays by scholars

- Lee, R. Alton. Truman and Taft-Hartley: A Question of Mandate. (1966) online edition

- Leuchtenburg, William E. The White House Looks South: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Lyndon B. Johnson. (2005). 668 pp.

- Levantrosser, William F. ed. Harry S. Truman: The Man from Independence (1986). 25 essays by scholars and Truman aides. online edition

- McCoy, Donald. The Presidency of Harry S. Truman (1984), standard scholarly survey by conservative historian; excerpt and text search

- Marcus, Maeva Truman and the Steel Seizure Case: The Limits of Presidential Power (1994) online edition

- Phillips, Cabel. The Truman Presidency: The History of a Triumphant Succession (1966), by a journalist who interviewed many key players

- Pierpaoli, Paul G. Jr. Truman and Korea: The Political Culture of the Early Cold War. (1997). ISBN 0-8262-1206-9. focus on the homefront online review

- Pietrusza, David 1948: Harry Truman's Improbable Victory and the Year that Changed America (2011)

- Ryan, Halford R. Harry S. Truman: Presidential Rhetoric (1993) online edition

- Sitkoff, Harvard. "Harry Truman and the Election of 1948: The Coming of Age of Civil Rights in American Politics," Journal of Southern History, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Nov., 1971), pp. 597–616 in JSTOR

- Theoharis, Athan. "The Truman Administration and the Decline of Civil Liberties: The FBI's Success in Securing Authorization for a Preventive Detention Program," Journal of American History, Vol. 64, No. 4 (Mar., 1978), pp. 1010–1030 in JSTOR, leftwing attack on Truman for being too harsh on possible subversives

- Theoharis, Athan. The Truman Presidency: The Origins of the Imperial Presidency and the National Security State (1979), revisionist, New left attack on HST

- Theoharis, Athan. Seeds of Repression: Harry S. Truman and the Origins of McCarthyism (1977), New Left attack on HST for being so hostile to domestic Communists

- Thompson, Francis H. The Frustration of Politics: Truman, Congress, and the Loyalty Issue, 1945-1953. 1979. 246 pp.

- Vaughan, Philip H. "The Truman Administration's Fair Deal for Black America." Missouri Historical Review 1976 70(3): 291–305. Issn: 0026-6582

Primary sources

- Bernstein, Barton J., Ed. The Truman Administration: A Documentary History (1966); 2nd edition published as Politics and Policies of the Truman Administration (1970), revisionist

- Council of Economic Advisors, Economic Report of the President (annual 1947- ), complete series online; important analysis of current trends and policies, plus statistcial tables

- Ferrell, Robert H. ed. Dear Bess: The Letters from Harry to Bess Truman, 1910-1959 (1983)

- Ferrell, Robert H. ed. Off the Record: The Private Papers of Harry S. Truman (1980).

- Merrill, Dennis. ed. Documentary History of the Truman Presidency, (1995- ) 35 volumes; available in some large academic libraries.

- Miller, Merle Plain Speaking: An Oral Biography of Harry S. Truman (1974)

- Neal, Steve. ed. HST: Memories of the Truman Years. (2003)280pp; long excerpts from 20 oral history interviews (some of which are online at the Truman Library site).

- Neal, Steve. ed. Miracle of '48: Harry Truman's Major Campaign Speeches & Selected Whistle-Stops (2003); 43 speeches

- Truman, Harry S. Where the Buck Stops: The Personal and Private Writings of Harry S. Truman edited by Margaret Truman (1990) excerpt and text search

- Truman, Harry S. Memoirs 2 vol (1955). vol 1 online

- Truman, Margaret. Harry S. Truman. (1973). memoir by his daughter

- Truman, Harry S. The Autobiography of Harry S. Truman edited compilation of excerpts by Robert H. Ferrell (2002) excerpt and text search

- The Public Papers of the Presidents contain most of Truman's public messages, statements, speeches, and news conference remarks. Documents such as Proclamations, and Executive Orders

Historiography

- Ferrell, Robert H. Harry S. Truman and the Cold War Revisionists. 2006. 142 pp. excerpt and text search

- Geselbracht, Raymond. "Creating the Harry S. Truman Library: The First Fifty Years," Public Historian, 28 (Summer 2006), 37–78.

- Hartmann, Susan M. "The 1948 Election and the Configuration of Postwar Liberalism" Reviews in American History 28.1 (2000) 105-111 in Project Muse

- Heller, Francis H., ed. The Korean War: A 25 Year Perspective (1977), essays by scholars

- Heller, Francis H., ed. The Truman White House: The Administration of the Presidency, 1945-1953 (1980), essays by scholars

- Heller, Francis H., ed. Economics and the Truman Administration (1981), essays by scholars

- Kirkendall, Richard S. ed. Harry's Farewell: Interpreting and Teaching the Truman Presidency (2004) essays by scholars

- Kirkendall, Richard S., ed. The Truman Period as a Research Field: A Reappraisal 1972 (1974)

- Tull, Charles J. "The State of the Art in Truman Research," in William F. Levantrosser, ed. Harry S. Truman: The Man from Independence (1986), 1-31 aides. online edition

- Walker, J. Samuel "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: a Search for Middle Ground." Diplomatic History 2005 29(2): 311–334. Issn: 0145-2096 Fulltext: Ebsco

References

- ↑ Evans, Farrell (November 5, 2020). Why Harry Truman Ended Segregation in the US Military in 1948 History.com. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ↑ His middle initial, S, does not stand for anything, but was chosen because his parents could not decide whether to name him for his grandfather Shippe or for his grandfather Solomon.

- ↑ David McCullough, Truman (Simon and Schuster, 2003, ISBN 0743260295), p. 237

- ↑ Margaret Truman, Harry S. Truman (Morrow, 1972) ISBN 0688000053, p. 67

- ↑ David McCullough, Truman (Simon and Schuster, 2003, ISBN 0743260295), p. 166

- ↑ David McCullough, Truman (Simon and Schuster, 2003) ISBN 0743260295, p. 242

- ↑ Memorable quotes for Truman (1995) (TV), Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Greenbaum, Fred (1967). "The Anti-Lynching Bill of 1935: The Irony of "Equal Justice—Under Law"," p. 83. Internet Archive. Retrieved December 3, 2022.

- ↑ "Clear everything with Sidney", Time magazine, Sep. 25, 1944.

- ↑ The Roosevelt Myth, John T. Flynn, Fox and Wilkes, 1948, Book 2, Ch. 8, The Shock Troops of the Third New Deal

- ↑ Roosevelt Myth, Book 3, Ch. 10, Politics, Disease and History, Flynn, 1948.

- ↑ Truman, Interview with David McCullough, C-Span Booknotes, July 19, 1992. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ↑ The Yalta Betrayal, Felix Wittmer, Claxton Printers, 1953, pg. 75.

- ↑ New York Times March 14, 1983.

- ↑ J. Samuel Walker, "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: a Search for Middle Ground." Diplomatic History 2005 29(2): 311-334. Issn: 0145-2096 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ↑ The memo until 1991 was mis-attributed to Clifford, who passed it along to Truman.

- ↑ Reagan was an energetic liberal supporter of Truman. He moved to the right in the late 1950s.

- ↑ Steven M. Gillon, Politics and Vision: the ADA and American Liberalism, 1947-1985 (1987).

- ↑ Steven F. Lawson, ed. To Secure These Rights: The Report of Harry S. Truman's Committee on Civil Rights. (2004)

- ↑ Bernard C. Nalty, Strength For the Fight: A History of Black Americans in the Military (1986)

- ↑ Alan L. Gropman, The Air Force Integrates, 1945-1964. (2nd ed 1998) online edition.

- ↑ Richard M. Dalfiume, Desegregation of the U.S. Armed Forces: Fighting on Two Fronts, 1939-1953. (1969)

- ↑ Thurmond received only 15% of the vote in the other Southern states. Kari Frederickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968. (2001)

- ↑ Time magazine reported that "His irresponsible implication that a vote for Thomas Dewey was a vote for fascism horrified his soberer followers." Time Jan 3, 1949 at [1]

- ↑ Harold I. Gullan, The Upset That Wasn't: Harry S. Truman and the Crucial Election of 1948 (1998); Gary A. Donaldson, Truman Defeats Dewey (1998)

- ↑ See Dean (2006)

- ↑ Karen J. Bradley, "Agrarian Ideology and Agricultural Policy: California Grangers and the Post-world War II Farm Policy Debate," Agricultural History 1995 69(2): 240-256, in JSTOR

- ↑ Turkey did not have an insurrection, but it was such a bitter rival of Greece that it had to get money if Greece did.

- ↑ Joseph C. Satterthwaite, "The Truman Doctrine: Turkey," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 401, (May, 1972), pp. 74-84 in JSTOR

- ↑ Michael T. Benson, Harry S. Truman and the Founding of Israel (1997) excerpt and text search; for the State Department perspective see Evan M. Wilson, "The American Interest in the Palestine Question and the Establishment of Israel," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 401, (May, 1972), pp. 64-73 in JSTOR

- ↑ Pollak, Joel B. (May 14, 2017). Today in History: Harry Truman Defies State Department, Recognizes Israel. Breitbart News. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ↑ Elizabeth Edwards Spalding, "True Believers" Wilson Quarterly 2006 30(2): 40-44, 46-48. Issn: 0363-3276 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ↑ Military Situation in the Far East, Hearings before the Committee on Armed Services and the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, 82nd Congress (Washington, 1951), p. 558.

- ↑ Tang Tsou, America's Failure in China, 1941-1945, Chicago 1964, pg. 457.

- ↑ Richard C. Thornton, China: A Political History, 1917-1980, Boulder CO 1982, pg. 208.

- ↑ Hearings before the Senate Committee on Armed Services and Committee on Foreign Relations (also known as the MacArthur Inquiry), June 2, 1951.

- ↑ Hearings before the Senate Committee on Armed Services and Committee on Foreign Relations, June 6, 1951.

- ↑ Report of the Commission on Protecting and Reducing Government Secrecy. Senate Document 105-2. 103rd Congress. Washington, D.C. United States Government Printing Office. 1997. Chairman's Forward, pg. XL pdf.

- ↑ By 1946 he had two valuable aides Clark Clifford and George Elsey.

- ↑ https://www.trumanlibrary.org/whistlestop/study_collections/korea/large/documents/pdfs/kr-3-13.pdf

- ↑ A General's Life by Omar N. Bradley, pg. 528

- ↑ The Forgotten War Remembered, Korea: 1950-1953: A War Correspondent's Notebook & Today's Danger in Korea by Bill Shinn, pg. 52

- ↑ https://2009-2017.state.gov/p/io/potusunga/207324.htm

- ↑ Truman's wife accepted an expensive deep freeze appliance in 1945; with General Vaughan as the fixer, the donor was given special privileges in Europe.

- ↑ Kirkendall, Truman Period as a Research Field: A Reappraisal 1972 (1974) p 6

- ↑ Quotes from Offner (2002) p. xii

- ↑ A field guide to pigs By John Pukite

- ↑ Harry S. Truman, “Exchange of Messages with Pope Pius XII,” American Presidency Project, August 6, 1947.

External links

- Biography

- Presidential Library

- The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb, Truman Library.

- President Truman to Senator Richard B. Russell, August 9, 1945.

- Works by Harry S. Truman - text and free audio - LibriVox

| |||||

| |||||

- Presidents of the United States

- Vice Presidents of the United States

- Missouri

- World War II

- Democratic Party

- Former United States Senators

- Cold War

- United States History

- Liberals

- 1950s

- New Deal

- Racism

- United States Veterans

- Soldiers

- Corruption in Democrat Party

- Featured articles

- Moderate Democrats

- Pro Israel

- Old Left

- KKK Members

- Pro-Surveillance

- Southern Baptists

- Freemasons