| Woodrow Wilson | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 28th President of the United States From: March 4, 1913 – March 4, 1921[1] | |||

| Vice President | Thomas R. Marshall | ||

| Predecessor | William Howard Taft | ||

| Successor | Warren G. Harding | ||

| 34th Governor of New Jersey From: January 17, 1911 – March 1, 1913 | |||

| Predecessor | John Fort | ||

| Successor | James Fielder | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Democratic party | ||

| Spouse(s) | Ellen Axson Wilson Edith Galt Wilson | ||

| Religion | Presbyterian | ||

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856 - 1924) was the intellectual leader of the Progressive Movement at the time he was elected as the 28th President of the United States of America, and reelected in 1916, serving from 1913 to 1921. Wilson was a Darwinian racist who supported eugenics as other believers in the theory of evolution did, and he even segregated civil servants after they had been integrated. In 2020, the liberal elite dropped him down the memory hole and removed his name from prestigious programs, including Princeton University's politics program despite how he had been president of the university.

Supported by progressives, Wilson created the Federal Reserve System, lowered tariffs, and revised the antitrust laws in a way that ended most of the "trust-busting" and drew clear lines on what was allowed. He supported liberal policies such as raising wages of railroad workers when they threatened a nationwide strike in 1916. Trying repeatedly and failing to broker peace during World War I, Wilson broke his campaign pledge to stay out of World War I by leading the United States into the war in 1917. He set up a draft and trained millions of soldiers, sending the American Expeditionary Forces to France under the command of General John J. Pershing. Woodrow Wilson was also notoriously anti-Catholic,[2] and was known for his racist policies promoting segregation, and promoted eugenics based on Darwinist theory.[3]

Wilson played a dominant role in ending the war with his Fourteen Points and played the central role at the Versailles Conference that set the peace terms in 1919. He was the idealist who envisioned a new international order founded on self-determination, unfettered international trade, the end of militarism, and a worldwide organization of states - the League of Nations. He failed to obtain Senate approval for the Versailles treaty because it required American entry into the League of Nations and a possible loss of control over the war-making power. Wilson refused to involve the Republicans in the peace-making, even though they controlled Congress, and refused the Lodge Reservations, a GOP compromise that would have allowed American entry into the League without giving up sovereignty.

Wilson was a very complex man who was unwilling to accept America's founding. He rejected the doctrine of the Founders of the Republic in the preface to the Declaration of Independence that people are "endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights" and asserted the Hegelian principle that the citizen should "marry his interests to the state". Ironically, Woodrow Wilson laid the foundations for a state that has no use for God and uses “every means. . .by which society may be perfected.” And today Wilson's ideological heir, Barack Obama, carried out his grandiose plan that declares the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution relics of the distant eighteenth century and seeks to bring everyone and everything, including religious groups, under control of the state. He ranks with Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Lyndon B. Johnson and Ronald Reagan as the nation's most active and dominant chief executives. He ranks with Abraham Lincoln and Reagan as the most articulate spokesman for national values. He was a war president who largely ignored military affairs and focused on very complex diplomatic issues. He won his war, reshaped the world at the peace conference, and saw his nation reject his idealist League of Nations because he refused to work with Republicans on its mechanics.

A rigid, self-exacting personality, whose uncompromising adherence to principles barred agreement on some of his most important political goals, he was a brilliant opportunist who won stunning electoral victories and led controversial laws through Congress. He understood diplomacy and domestic affairs in depth, and was the first to recognize a solution that could satisfy most of the needs of the interested parties. He was willing to negotiate endlessly, usually getting his way in the end, especially when his powerful rhetoric energized his backers. A devout Presbyterian who studied the Bible every day, he elevated a religious style of idealism to the central place in American diplomacy. A lonely intellectual, he had few friends, and broke one-by-one with his closest advisors, until in his last two years in office he was an invalid controlled in large part by his wife.

Wilson's idealistic foreign policy, called "Wilsonianism" sought to end militarism as a force in world affairs, vigorously promote national self-determination, create international bodies to head off serious disputes, and use American resources to promote democracy. Wilsonianism (and "idealism" generally) is opposed to "realism" in foreign policy, which stresses a concern for American self-interest, especially in economic and military terms. Wilsonianism reshaped the world in the aftermath of the Great War; its values lie at the core of the foreign policy of George W. Bush (2001-2009).

Wilson was the most profoundly Christian political leader in the world in the 20th century. He felt assured that he was following God's guidance. Wilson considered the United States a Christian nation destined to lead the world. He was a prophet and a postmillenarian, and if idealism clashed with reality, he was certain idealism would prevail.

Steven Crowder, David Barton, and "Tim" offered a detailed analysis of Woodrow Wilson's racism ahead of Independence Day 2020 in a segment dedicated to black history.[4]

Family

Wilson's father Joseph Ruggles Wilson (1822-1903), born in Ohio, was a Presbyterian minister of Scotch Irish descent. Woodrow's mother Jesse was born in Carlisle, England, to a Scottish-born Presbyterian minister; her family moved to Canada in 1835 and to Ohio in 1837. Woodrow's parents moved South in 1851, owned house slaves, and identified themselves with the culture and political values of the South. The father Joseph Wilson was a theologian, defended slavery and soon emerged as a leader of the Southern Presbyterian Church and an avid supporter of the Confederacy.[5]

Wilson's grandfather (Joseph Wilson's father) was James Wilson, who immigrated to the United States from northern Ireland in 1807 and was first an editor of the Jeffersonian Republican newspaper the Aurora in Philadelphia, and later published Whig newspapers in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Since his father had been ostracized by the northern relatives, Woodrow had no contact with his grandfather or uncles, who were active in antislavery Republican politics in Ohio and Pennsylvania.[6]

Woodrow grew up in the South during the Civil War and Reconstruction his father was a chaplain for the Confederate army. Woodrow saw the humiliation, economic ruin and shame that the loser of a war experiences and the hatred that grows from this, as well as the rampant corruption during Reconstruction in Columbia, the capital of South Carolina. A victim of childhood dyslexia, he became an avid reader. His father imparted a love of literature and politics to his son; much family activity revolved around Bible readings, daily prayers, and worship services at the father's church.

In 1885 Wilson married Ellen Louise Axson (1860 – 1914), the daughter of a Presbyterian minister in Savannah, Georgia. She was an accomplished painter and a successful hostess; they had three daughters.[7]

Education

Woodrow studied at Davidson College in North Carolina in 1873-1874 and at Princeton University from 1875 to 1879. He proved an exceptional student, primarily interested in debate and politics. His father always wanted him to be a minister; Wilson greatly admired the British Prime Minister William E. Gladstone, a Christian in politics, and decided to emulate him. Wilson saw politics as a divine vocation—to be a statesman was an expression of Christian service, he believed, a use of power for the sake of principles or moral goals. Wilson saw the "key to success in politics" as "the pursuit of Perfection through hard work and the fulfillment of ideals." Politics would allow him to spread spiritual enlightenment to the American people.

He was an editor of the Princetonian and wrote his senior thesis on "Cabinet Government in the United States;" it was later published. The essay stressed the superior qualities of the British cabinet system and said it ought to be tried in the United States.[8] After graduation in 1879 he studied law at the University of Virginia; he was admitted to the bar and practiced in Atlanta, in 1882. It was too boring. Wilson's scholarship led him in 1883 to enter the new Johns Hopkins University graduate school where he studied government and history, taking a PhD in 1885. Wilson is the only president to have earned a PhD.

During his studies at "The Hopkins", one of Wilson's most prominent professors was Richard T. Ely, a leader of the Social Gospel movement.[9]

Academia

In 1885 Wilson was appointed as a history instructor at Bryn Mawr College, an elite Quaker school for women near Philadelphia, at a salary of $1500 a year (which was enough to hire a servant). In 1888 he moved to Wesleyan University, a Methodist college in Connecticut. His reputation as an outstanding leader in political science brought him a professorship of jurisprudence and political economy at Princeton University in 1890. For the next twelve years he taught at Princeton, popular alike with students and faculty; he became the president of the school in 1902.[10][11]

Wilson soon emerged as the nation's foremost academic, in heavy demand in elite circle for his brilliant speeches.

Wilson subscribed to the Social Darwinist view that survival was for the fittest races, and he supported the Eugenics movement. He believed there are “progressive races” such as Anglos and Aryans, who had superior and enlightened governments, and “stagnant nationalities” – Eastern and Southern Europeans – who needed authoritarian governments to control them.

At Princeton he created academic departments but otherwise downplayed the Germanic model of the PhD-oriented research university in favor of the "Oxbridge" (Oxford and Cambridge) model of intense small group discussions and one-one-one tutorials. He hired 50 young professors, called preceptors, to meet with students in small conferences, grilling them about their reading. Complaining that Princeton was dominated by "eating clubs" in which students ate with each other and ignored the professors, he sought to build Oxford-style colleges where students and faculty would eat and talk together. He failed—the eating clubs are still there.[12]

Wilson promoted the leadership model, whereby the college focused on training a small cadre of undergraduates for national leadership, "the minority who plan, who conceive, who superintend," as he called them in his inaugural address as the university's president. "The college is no less democratic because it is for those who play a special part." He confronted the dean of the graduate school, who had the German research model in mind and outmaneuvered Wilson by obtaining outside funding for a graduate complex for serious scholarship that was well separated from the fun-loving undergraduates.

Political theory

Political Science

Wilson made significant contributions to political science.[13] In 1885 he published his influential treatise Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics, based on his PhD dissertation. It set a new standard in analyzing the actual workings of the federal government with striking clarity and thoroughness. The citizen must “marry his interests to the state.” Wilson, therefore, dismissed the Declaration's assertion that rights are endowed by our Creator. Wilson lectured that, “If you want to understand the real Declaration of Independence, do not repeat the preface.” “The rhetorical introduction,” he declared, “is the least part of it.”

Although Wilson had never visited Congress, his emphasis on the centrality of committees in Congress was a major contribution to the study of political science. Noting how the Constitution's separation of powers had been eroded since the Civil War by the increasing power of Congress, he suggested a remedy for this in a cabinet-style government of the variety proposed by Walter Bagehot in Britain. By criticizing the Constitutionalist and Federalist traditions that had characterized American politics for a century, and showing their faults, Wilson sought to open a serious debate on the political changes in the United States in the intervening century and whether the Constitution remained an adequate regulator of these. By the time he wrote Constitutional Government in the United States (1908), Wilson was advocating the need for constitutional reform that would make Congress and president more representative and, above all, the need for a strong president who could influence Congress rather than submit to it. In Constitutional Government, Wilson creates the idea that the Constitution is a living and breathing document.[14]

Wilson originated the notion that political parties, besides running campaigns, need to be responsible for clearly designed public policies, which they present to the electorate for approval. The key to responsibility was the presidency. Hegelian conceptions of monarchy strongly influenced Wilson, and his view of public opinion contrasted sharply with the Madisonian view of factionalism. Consequently, Wilson viewed parties as primarily the machinery through which strong leaders interpret and pursue the public will.[15]

Deeply alarmed by labor and agrarian radicalism in the 1890s, Wilson resolved to cleanse the Democratic Party of Populist influence. His political vision ultimately sought to adapt American society to the new economic conditions of the 20th century, chiefly defined by the magnification of corporate power.

Public administration

- See also: The Study of Administration and Administrative State

Wilson was a founder of the study of public administration by political scientists. Wilson believed in a strong, active role for the central government and as president succeeded in establishing legislation that significantly enlarged its regulatory powers. With the publication of Congressional Government in 1885, Wilson established himself as a leader of the political reform movement of the day. The book was the first of its kind to analyze policymaking by the central government and to provide recommendations for changing the process. Wilson was one of the three most prominent public administrationists of the 1880s and 1890s. As an academician, he promoted a separate department for the study of public administration and wrote 'The Study of Administration' (1887), the first published essay by a university scholar on the subject, established Wilson as the leading authority in the field.

During the next year he inaugurated a course in public administration at Johns Hopkins University, providing three 6-week lecture series arranged in a 3-year cycle. In 1889, Wilson published a textbook, The State, and, in 1891, he began at Hopkins a new 3-year course which was a further significant step in the development of the study of administration. He was one of the first scholars to realize fully that all government was ultimately to be administration.[16]

Philip Dru

On November 16,[17] 1912,[18] President-elect Wilson took a trip to Bermuda. For the trip, he was given a copy of Philip Dru: Administrator[19] by his adviser Edward House[20] for his reading pleasure.[21] Describing the similarities between Woodrow Wilson and Philip Dru, Franklin K. Lane, who served as Secretary of the Interior for seven years, made the following observations:

| “ | Colonel House's Book, Philip Dru, favors it, and all that book has said should be, comes about slowly, even woman suffrage. The President comes to Philip Dru in the end. And yet they say that House has no power....[22] | ” |

Football

Wilson as president of Princeton, and Theodore Roosevelt as president of the United States, took an intense interest in the controversy over the reform of college football. In the 1890s and early 1900s, college football faced sharp of criticism over injuries and the role of athletics in college life. Roosevelt and Wilson, loyal followers of Harvard and Princeton, had defended football in the 1890s. In the fall of 1905, however, President Roosevelt called a conference of football experts at the White House to discuss brutality and unsportsmanlike conduct. Thereafter, Roosevelt worked behind the scenes to bring about sufficient reform to preserve football and ensure that it would continue to be played at Harvard. In the years 1909-10, when college football again faced an injury crisis, Wilson worked with the presidents at Harvard and Yale to make reasonable reforms. Both Roosevelt's and Wilson's approaches were consistent with their strategies for national political change. In the years that followed the reforms on the gridiron, football evolved rapidly into the 'attractive' game that Wilson had advocated and a far less brutal game than the unruly spectacle that Roosevelt had tried to control.[23]

Democrat

Many Civil War veterans were still alive and Wilson used the memory of the War to build nationalism and to facilitate reunion between the North and the South. In his academic work and public comments, Wilson stressed the theoretical and constitutional causes of the war, devaluing the slavery issue and stressing the moral equality of North and South, all in the interest of lessening sectional animosity. During World War I and the struggle for the League of Nations, Wilson frequently drew comparisons between Lincoln and the Union's sacrifices to save the nation and American soldiers' sacrifices during World War I to save the world. He succeeded in overcoming Southern isolationism by convincing the middle class in the region that God had preserved the Union in the Civil War in order to spread democracy throughout the world. He appealed to Southerners to demonstrate the patriotism that many said they lacked. He was able to convince them that they could wage war for democracy abroad without endangering white supremacy at home.[24]

Wilson despised post-Civil War Southern Reconstruction, which promoted African-American participation in public life. “The white men of the South,” he wrote in his History of America, “were aroused by the mere instinct of self-preservation to rid themselves, by fair means or foul, of the intolerable burden of governments sustained by the votes of ignorant Negroes and conducted in the interest of adventurers.” As president, Wilson re-segregated the federal government.

Progressive governor

As early as 1906 Wilson came under the influence of Colonel George Harvey (1864-1928), a Democrat who owned a publishing empire that included the New York World and Harper's Weekly magazine, reaching the nation's intellectual elite. Harvey, with close ties to Wall Street and J. P. Morgan, saw a future president and promoted Wilson heavily. Wilson became the intellectual leader of the anti-Bryan, anti-Populist wing of the Democratic Party. Harvey helped convince the old-fashioned bosses in New Jersey's cities to make Wilson the Democratic nominee for governor in 1910, explaining this would bring in the middle class vote. Wilson, frustrated at Princeton, made the move and was elected. Wilson then broke with the bosses, and Harvey, denounced Wall Street and the bosses, and electrified the nation with his Progressive reforms in the notoriously corrupt government of New Jersey. Wilson by 1912 had emerged as the cleanest, most religious, best known and most dynamic leader of the Progressive Movement in the Democratic Party.

George Harvey was the first person to recommend Wilson for the presidency.[25][26]

Election of 1912

William Frank McCombs, a New York lawyer and a friend from college days, instigated and managed Wilson's campaign for president in 1912. Much of Wilson's support came from the South, especially from young progressive professionals. Wilson managed to maneuver through the complexities of local politics. For example, in Tennessee the Democratic Party was divided on the issue of prohibition. Wilson was progressive and sober, but not a dry, and appealed to both sides. They united behind him to win the presidential election in the state, but divided over state politics and lost the gubernatorial election.[27]

At the convention deadlock went on for over 40 ballots as a two-thirds vote was needed. A leading opponent was House Speaker Champ Clark, a prominent progressive strongest in the border states. Other contenders were Judson Harmon of Ohio, and Oscar Underwood of Alabama. They lacked Wilson's charisma and dynamism. Clark was supported by publisher William Randolph Hearst, a leader of the left-wing of the party. The critical role was played by William Jennings Bryan, the nominee in 1896, 1900 and 1908, who blocked the nomination of any candidate who had the support of 'the financiers of Wall Street.' He finally announced for Wilson, who won on the 46th.[28]

In the three-way contest, Wilson received fewer popular votes than the Democrat loser William Jennings Bryan did in 1896. Some historians however believe that Wilson's election was a defining moment in American history. The former political science professor's views on government and human nature (and the relationship to the state) became the foundations of Democratic Party statism. Historians agree that Wilson had a dark side with a strong dislike of immigrants, particularly Catholics and African-Americans.

Initially, Wilson enjoyed the support of some black leaders, including W.E.B. DuBois. Wilson's speeches and letters expressed sentiments as a defender of the generic underprivileged. However the rejoicing over Wilson's victory was short-lived among blacks as segregationist white Southerners took control of Congress and Wilson appointed many to executive departments.[29]

In the campaign Wilson promoted the "New Freedom," emphasizing limited federal government and opposition to monopoly powers—positions that he reversed on coming to office.

President William Howard Taft defeated ex-President Theodore Roosevelt in a bitter contest for the Republican nomination, but Roosevelt walked out of the Republican convention and ran as a third party candidate. Wilson's success in the electoral college was assured, despite his 41.8% of the popular vote.[30]

President: 1913-21

Taking advantage of a deep split in the GOP, the Democrats took control of the House in 1910 and elected the segregationist Woodrow Wilson as president in 1912 and 1916. In his first year in office, Wilson permitted his Treasury and the Post Office to begin efforts to segregate the federal workforce, particularly in the Columbia District. It was often carried out surreptitiously. Yet Wilson condoned it and tried to duck its implications in a manner we would describe today as slimy. Wilson ordered Jim Crow segregation in all federal government facilities in Washington DC, wiping out 50 years of social progress that African-Americans made under Republicans. No longer could blacks and whites work together in government offices, eat in the same cafeterias, our use the same bathrooms. The Wilson administration went a step further. Through the Treasury Department's Office of the Architect, the bureau charged with construction and maintenance of federal buildings, federal buildings throughout the nation were ordered to furnish segregated bathrooms, even in Northern states were practices as such were virtually unknown.[31]

First term

In his first year in office, Wilson permitted his Treasury and the Post Office to begin efforts to segregate the federal workforce, particularly in the Columbia District. It was often carried out surreptitiously. Yet Wilson condoned it and tried to duck its implications in a manner we would describe today as slimy. He also curtailed minority appointments to executive, diplomatic, and judicial positions.

Those latter numbers weren’t large — about 30 — but they were posts traditionally reserved for black Americans. The signal was terrible, even if it’s unclear that those black appointments would have met approval from a Senate controlled by Southern Democrats. Estimates reckon that between 15,000 and 20,000 black civil service employees, 6% of the federal workforce, were impacted by the administration’s actions.[32]

Domestic policy

Wilson successfully led Congress to a series of Progressive laws, including a reduced tariff, stronger antitrust laws, the Federal Reserve System, hours-and-pay benefits for railroad workers, and outlawing of child labor, raising wages for adults. Furthermore, constitutional amendments for prohibition and woman suffrage were passed in his second term. In effect, Wilson laid to rest the issues of tariffs, money and antitrust that had dominated politics for 40 years.

In 1915 the epic Hollywood film, Birth of a Nation was released with its portrayal of black men, many played by white actors in blackface, as unintelligent and sexually aggressive towards white women, and the portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) as an heroic force.[33][34] It was the first American motion picture to be screened inside the White House, viewed there by Wilson, members of his cabinet, and their families.[35] In a letter to the White House press secretary the author of The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan which the film is based,[36] wrote:

| “ | "The real purpose of my film was to revolutionize Northern sentiments by a presentation of history that would transform every man in the audience into a good Democrat...Every man who comes out of the theater is a Southern partisan for life!"[37] | ” |

In a letter to President Wilson, Thomas Dixon Jr., who authored the book and screenplay, boasted:

| “ | "This play is transforming the entire population of the North and the West into sympathetic Southern voters. There will never be an issue of your segregation policy".[37] | ” |

Dixon was alluding to the fact that Wilson upon becoming president in 1913 had imposed segregation on federal workplaces in Washington D.C. while reducing the number of black employees through demotion or dismissal.[38]

Immigration

Wilson twice vetoed the Burnett Immigration Restriction Bill, which required a literacy test for immigrants and would have sharply reduced the number of poor immigrants from Poland, Italy and other parts of eastern and southern Europe. As a moderate progressive, Wilson believed southern and eastern European immigrants, though often poor and illiterate, to be capable of assimilation into a homogeneous middle class with other whites. He considered so-called hyphenated immigrants unacceptable because they acted as groups rather than blending into the common population. Indeed, he denounced the hyphenates. Wilson sought to achieve American strength through unity, blending together the best characteristics of every nationality to create the ideal citizenry, opposing Henry Cabot Lodge's nativist view that American civilization must be based on an Anglo-Saxon foundation. Immigration from Europe practically ended when the war began, so the issue was postponed ino the 1920s, when a quota system was set up to keep the country's ethnic balance unchanged.[39]

Foreign Policy

Mexico

The extremely violent civil war that broke out in Mexico in 1911 drove hundreds of thousands of refugees north across the border, and forced Wilson to intervene. Francisco Madero, an idealistic reformer who came to power in 1911. Madero tried to violently upend the social order in Mexico by destroying the landed aristocracy and the Catholic Church. When Madero was overthrown and murdered by Victoriano Huerta in February 1913, days before Wilson took office, he refused to recognize the new Mexican government. Relations deteriorated between the two countries. After American sailors were arrested in Tampico in April 1914 by Huerta's soldiers, the armed conflict loomed. American soldiers occupied Vera Cruz. In July 1914 Huerta fled to Spain. In 1916 the civil war between warlords Venustiano Carranza and Pancho Villa continued, and in March Villa raided Columbus, New Mexico, killing 20 Americans.[40] Wilson sent Brigadier General John J. Pershing deep into Mexico to capture Villa. Villa escaped the Americans. Despite the demands of outraged senators, Wilson did not declare war on Mexico. He ran for reelection in 1916 on the slogan, "He kept us out of war," meaning out of a war with Mexico.

Reelection

Woman suffrage

In the 1910s, suffragists campaigned for the passage of a federal constitutional amendment that would grant women the right to vote. They argued it would purify politics because the new voters would be far less liable to corruption and saloon influences. The movement was led by Protestant northern women, many of whom were active in the prohibition movement at the same time. Wilson, originally opposed to the amendment, was converted through the efforts of women suffragists and became an advocate of critical importance. Both the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the National Women's Party (NWP) used symbolic representations of President Wilson, conferring on him real or symbolic images of presidential power. In practice Wilson hedged, realizing that male Democrats in the big city machines in the North and in the rural South were hostile to woman suffrage. The meaning of democracy was at issue: the NWP portrayed Wilson as a tyrant, the NAWSA depicted him as a champion of freedom. Both organizations played essential roles in the passage of the 19th Amendment. After 1919, the absence of a common goal was a contributing factor to the subsequent divisions within the woman's rights movement, as was the loss of a unique adversary.[41]

Second term

Entering the war

Domestic policy

Wilson established the Committee on Public Information to disseminate approved information, and nationalized the railroads under the control of the United States Railroad Administration.

Foreign Policy

Russia

Wilson's commitment to the principle of self-determination affected his decision to intervene in Russia in 1918, as the Bolsheviks (Communists) took power. Unswayed by British, French, and Japanese pressure, Wilson insisted that, unless the Russians invited them, the Allies should not interfere with Russia's internal affairs. In the summer of 1918, the president sent American troops into Siberia with the sole purpose of protecting Czechoslovak soldiers who had broken out of POW camps and were an independent force. Later Wilson realized that the other Allied nations were using the rescue mission as an 'anti-Bolshevik' crusade and for imperialistic motives. As a result, the president ordered US forces to withdraw. Wilson and subsequent presidents until 1933 refused to recognize the new Communist government, and Russia was not invited to the Paris Peace Conference.[42]

Mideast

In November 1917, Wilson endorsed the pro-Zionist Balfour Declaration issued by Britain. Wilson's aims in this endorsement were both practical and religious. His deep Christian sentiment led him to seek 'a direct governing role in the Near East in the name of peace, democracy and, especially, Christianity. By agreeing to the use of the mandate system by which the transition governments of the Middle East were partially controlled by Britain and France after the war, Wilson was both contradicting and reaffirming his own ideals by allowing only limited self-determination of Middle-Eastern peoples while assuring some respect for property and order.[43]

Paris Peace Conference, 1919

President Wilson was present at the Post-World War I Paris Peace Conference, becoming the first President to ever visit Europe whilst in Office.

When President Wilson left for Europe in 1919 to establish a new world order at the 1919 Versailles Conference, European Catholics were justifiably concerned about the treatment their former homelands would receive from the victorious allies. Along with Prime Ministers David Lloyd George of the United Kingdom and Georges Clemenceau of France, the three were collectively known as the Big Three and met and discussed the peace treaties that would shape post-war Europe. President Wilson pushed for terms that were not too harsh on the already war-crippled Germany, though the British and French leaders pushed for the infamous 'War Guilt Clause' that declared Germany guilty of the war and forced her to pay harsh reparations. To save his League of Nations, Wilson abandoned his mighty rhetoric and ideals at Versailles and managed to alienate almost every Catholic by surrendering to the demands of the vengeful leaders of the victorious allies. He planted the seeds of World War II when he rearranged the boundaries of Eastern Europe without regard for the ethnic or religious origins of millions of people.

Wilson particularly pushed for the League of Nations to be created, a precursor to today's United Nations.

Fight for the League

After the Paris Peace conference, Wilson came home to try to convince the Senate to ratify the treaty which would create the League. But on September 26, 1919, Wilson came home from a series of speeches he was making around the country, because of a series of strokes he had suffered which left him debilitated.[44]

In 1920, during the time period of which Wilson was incapacitated, Wilson's wife Edith allowed for Louis Seibold of the New York World to conduct an interview with Wilson. Seibold, along with Edith Wilson and Wilson's Chief of Staff Joseph Patrick Tumulty, produced a fabricated interview for which Seibold won a Pulitzer Prize in 1921.[45]

After the war

After the conclusion of World War I and the closing year of the Wilson presidency, there was a sharp depression, which many historians have decided not to write about.

Wilson and religion

A Presbyterian of deep religious faith, he appealed to a gospel of service and infused a profound sense of moralism into Wilsonianism.[46]

Link finds that Wilson from his earliest days had imbibed the beliefs of his denomination - in the omnipotence of God, the morality of the Universe, a system of rewards and punishments and the notion that nations, as well as man, transgressed the laws of God at their peril.[47] Blum (1956) argues that he learned from William Gladstone a mystic conviction in the superiority of Anglo-Saxons, in their righteous duty to make the world over in their image. Moral principle, constitutionalism, and faith in God were among the prerequisites for alleviating human strife. While he interpreted international law within such a brittle, moral cast, Wilson remained remarkably insensitive to new and changing social forces and conditions of the 20th century. He expected too much justice in a morally brutal world which disregarded the self-righteous resolutions of parliaments and statesmen like himself. Wilson's triumph was as a teacher of international morality to generations yet unborn.[48] Daniel Patrick Moynihan sees Wilson's vision of world order anticipated humanity prevailing through the "Holy Ghost of Reason," a vision which rested on religious faith.[49]

Wilson was a Presbyterian elder and the son of a leading theologian. He read the Bible daily; he felt 'sorry for the men who do not read the Bible every day.' The Bible, he argued, was 'the one supreme source of revelation of the meaning of life.' Wilson was prone to make explicitly Christian claims about his nation, even excluding the word Judeo from his characterization of the nation's religious heritage. 'America was born a Christian nation,' he explained in a speech on "The Bible and Progress" in 1911: "America was born to exemplify that devotion to the elements of righteousness which derived from the revelations of Holy Scripture."[50]

He held that the Bible "is the one supreme source of revelation, the revelation of the meaning of life, of the nature of God and the spiritual nature and need of men. It is the only guide of life which really leads the spirit in the way of peace and salvation."[51]

God was central in Wilson's life and thought. His profound Presbyterian style of thinking assured him that he was following God's guidance. Wilson personified American optimism and considered the United States a Christian nation destined to lead the world. He was a prophet and a postmillenarian, and if idealism clashed with reality, he was certain idealism would prevail. He saw himself as God's messenger and statesman in a divinely predestined nation; thus he saw himself as God's agent in promoting democracy and world peace. His Fourteen Points and his Covenant of the League of Nations, were, in his view, divinely inspired paths to achieving a new world order.[52]

Anti-Catholic

Throughout his presidency Wilson had rocky relations with Roman Catholics. When Wilson recognized the Mexican government of President Venustiano Carranza, many Catholics were livid. The Catholic hierarchy forcefully complained that the United States should not support a government that restricted the public practice of Catholicism. The Jesuit magazine America condemned Wilson and described Carranza “as a villain, destroyer, liar and murderer.”

Wilson objected to the new wave of Catholic immigrants coming through the gates of Ellis Island. He wrote that there was “an alteration in stock which students of affairs marked with an uneasiness.” The sturdy European stocks, according to Wilson, were being replaced by “men of the lowest class from the south of Italy and men of the meaner sort out of Hungary and Poland, men out of the ranks where there was neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence.”

During the 1912 campaign, the American Association of Foreign Language newspapers struck a blow at Wilson: “No man who has an iron heart like Woodrow Wilson, and who slanders his fellowmen, because they are poor and many of them without friends when they come to this country seeking honest work and wishing to become good citizens, is fit to be President of the United States.”

These charges appeared to have had an effect. A poll of 2,300 Catholic priests in major inner-city Catholic strongholds revealed that 90 percent of the Italian and 70 percent of Polish priests intended to vote for Bull Moose candidate Theodore Roosevelt.

China policy

Wilson's discussions with Presbyterian missionaries visiting Princeton shaped his diplomacy toward China. Wilson viewed Christianity as a unifying force in the world and the Chinese Revolution of 1911 as the first step toward the spread of Christianity and democracy for China. Wilson gained the admiration of the missionaries and Chinese when he prohibited US participation in a European loan to China. He moved to recognize the government of Yuan Shih-k'ai, hoping that that regime could bring stability to China favorable to the introduction of Christianity. He sought to appoint an ambassador to China who could express Christian values. During World War I, missionaries successfully urged Wilson's opposition to Japanese demands on China. Although the war and its aftermath diverted Wilson from Chinese problems, his foreign policy continued to be influenced by missionaries, particularly Dr. Samuel I. Woodbridge and the Reverend Charles E. Scott.[53]

Living Constitution and statism

Also see Woodrow Wilson's lasting impact on the U.S. Constitution: Seventeenth Amendment

Wilson argued for a “Living Constitution” that “must be Darwinian in structure and in practice.” Government for him was “not a machine but a living thing. . . .It is modified by its environment, necessitated by its task, shaped to its functions by the sheer pressure of life.” He noted that the Framers "followed Newton" as they created the Constitution, making a comparison to planets in orbit around the sun. Interestingly enough, the Framers used that same analogy during the Constitutional Convention.[54][55]

Wilson believed that the citizen must “marry his interests to the state.” Wilson, therefore, dismissed the Declaration's assertion that rights are endowed by our Creator. Wilson lectured that, “If you want to understand the real Declaration of Independence, do not repeat the preface.” “The rhetorical introduction,” he declared, “is the least part of it.”

Wilson also rejected the premise described in the Federalist Papers, that checks and balances are needed because human nature is flawed and does not improve. He viewed the entire premise as outdated and a relic of a prior age, noting that "though they were written to influence only the voters of 1788, still, with a strange, persistent longevity of power, shape the constitutional criticism of the present day, obscuring much of that development of constitutional practice which has since taken place."[56]

Political philosopher Ronald Pestritto has observed that for Wilson, “the separation of powers, and all other institutional remedies that the founders employed against the danger of faction stood in the way of government’s exercising its powers in accord with the dictates of progress.”

Wilson advocated a new international order founded on self-determination, democracy, unfettered international commerce, and a worldwide organization of states - the League of Nations. Wilson framed American participation in the war as the first step in ending all wars. Although 'Wilsonian nationalism' has been blamed for the nationalistic emphasis on race and territory in Europe during the 1920s and 1930s, Wilson's policies had actually used ethnic and territorial issues to encourage self-determination and the development of democracy in postwar nations.

Woodrow Wilson's most lasting political philosophy was his view that democracy should be installed around the world. As a major player in setting the terms to end World War I, he helped to break up the Austrian-Hungarian Empire to advance his goal of installing democracy for each ethnic subpopulation. Similar independence was granted with the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. Many of these new nations were receiving self-determination for the first time in centuries. Wilson's view of installing democracy worldwide has since been copied by the neoconservatives. Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to start the League of Nations.

Historiography

Historians have been fascinated by Wilson and have vigorously defended him (Link) or attacked him (New Left). Since the collapse of the Communism in Europe in 1989, the mood had shifted in Wilson's favor. Even George Kennan, a harsh critic who favored "realism" against Wilson's idealism has changed his tune. The New Left attacks represented by Lloyd Gardner's highly critical A Covenant with Power have given way to Thomas Knock's laudatory To End All Wars. The leftist tendency to trace back to Wilson a tradition of economic self-seeking and arrogant interventionism has yielded to a new impulse to see Wilsonian diplomacy as having established "a new American agenda for world affairs," as Akira Iriye writes, built upon "the ideas of economic interdependence and of peaceful settlement of disputes."[57]

In recent years, a new generation of conservative historians highly focused on the roots of Progressivism, have become intensely critical of Wilson due to his key position in the early years progressive ideology.[58][59][60][61]

Works

Books:

- Congressional Government, (1885)

- George Washington, (1896)

- On Being Human, (1897)

- The State: Elements of Historical and Practical Politics, (1898)

- A History of the American People, (1902, five volumes)

- Constitutional Government in the United States, (1908)

- The New Freedom, (1913)

- When A Man Comes To Himself, (1915)

Essays:

- The Study of Administration, (1887)

- Leaders of Men, (1890)

Quotes

- "If America is not to have free enterprise, then she can have freedom of no sort whatever."[62]

- "Liberty has never come from Government. Liberty has always come from the subjects of it. The history of liberty is a history of limitations of governmental power, not the increase of it."[63]

- "We are in these latter days apt to be very impatient of literal and dogmatic interpretations of constitutional principle."[64]

- "Any man who can survive by his brains, any man who can put the others out of the business by making the thing cheaper to the consumer at the same time that he is increasing its intrinsic value and quality, I take off my hat to, and I say: 'You are the man who can build up the United States, and I wish there were more of you.'"

- "America was born a Christian nation. America was born to exemplify that devotion to the elements of righteousness which are derived from the revelations of Holy Scripture."[65]

- "A conservative man is a man who just sits and thinks, mostly sits."

See also

Bibliography

Biography

- Brands, H. W. Woodrow Wilson 1913-1921 (2003) excerpt and text search 169pp; good short summary by scholar

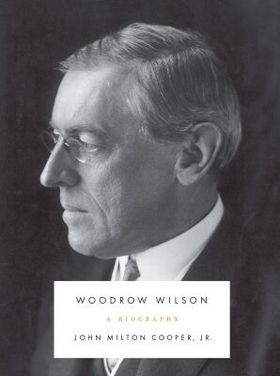

- Cooper, John Milton. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009), 720 pp. major new biography by leading scholar

- Cooper, John Milton. The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt (1985), fascinating double biography by leading scholar excerpt and text search

- Hofstadter, Richard. "Woodrow Wilson: The Conservative as Liberal" in The American Political Tradition (1948), ch. 10. influential essay; at ACLS E-books

- Link, Arthur S. "Woodrow Wilson" in Henry F. Graff ed., The Presidents: A Reference History (2002) pp 365–388

- Link, Arthur Stanley. Wilson: The Road to the White House (1947), first volume of standard biography (to 1917); Wilson: The New Freedom (1956); Wilson: The Struggle for Neutrality: 1914-1915 (1960); Wilson: Confusions and Crises: 1915-1916 (1964); Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916-1917 (1965), the last volume of standard biography; online at ACLS E-Books

- Maynard, W. Barksdale. Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency (2008) excerpt and text search

- Walworth, Arthur. Woodrow Wilson 2 Vol. (1958); Pulitzer prize winning biography vol 1 online; well-written but old-fashioned (it was written in the 1950s), it has been replaced by Cooper (2009).

Domestic affairs and ideas

- Abrams, Richard M. "Woodrow Wilson and the Southern Congressmen, 1913-1916," Journal of Southern History, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Nov., 1956), pp. 417–437 in JSTOR

- Clements, Kendrick A. The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson (1992), covers domestic and foreign policies; liberal tone

- Cooper, John Milton. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009), 720 pp.

- Cuff, Robert D. "Woodrow Wilson and Business-Government Relations during World War I," Review of Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Jul., 1969), pp. 385–407 in JSTOR

- Curti, Merle. "Woodrow Wilson's Concept of Human Nature," Midwest Journal of Political Science, Vol. 1, No. 1 (May, 1957), pp. 1–19 in JSTOR

- Daniel, Marjorie L. "Woodrow Wilson--Historian," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Dec., 1934), pp. 361–374 in JSTOR

- Dimock, Marshall E. "Woodrow Wilson as Legislative Leader," The Journal of Politics, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Feb., 1957), pp. 3–19 in JSTOR

- Link, Arthur S. Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910-1917 (1954), remains the standard history of his first term.

- Link, Arthur S. "Woodrow Wilson: The American as Southerner," Journal of Southern History, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Feb., 1970), pp. 3–17 in JSTOR

- Link, Arthur S. "Woodrow Wilson and the Democratic Party," Review of Politics, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Apr., 1956), pp. 146–156 in JSTOR cover 1913-14

- Livermore, Seward W. Woodrow Wilson and the War Congress, 1916-1918 (1966)

- Macmahon, Arthur W. "Woodrow Wilson as Legislative Leader and Administrator," American Political Science Review, Vol. 50, No. 3 (Sep., 1956), pp. 641–675 in JSTOR

- Malin, James C. The United States after the World War (1930)

- Pestritto, Ronald J. ed. Woodrow Wilson and the roots of modern liberalism (2005) ISBN 0742515176' argues Wilson subverted the ideas of the Founders by his progressivism

- Pietrusza, David 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents New York: Carroll & Graf, 2007.

- Saunders, Robert M. In Search of Woodrow Wilson: Beliefs and Behavior (1998)

- Turner, Henry A. "Woodrow Wilson and Public Opinion," Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Winter, 1957-1958), pp. 505–520 in JSTOR

- Wolgemuth, Kathleen L. "Woodrow Wilson and Federal Segregation," The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Apr., 1959), pp. 158–173 in JSTOR

- Weinstein, Edwin A., James William Anderson and Arthur S. Link. "Woodrow Wilson's Political Personality: A Reappraisal," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 93, No. 4 (Winter, 1978-1979), pp. 585–598 at JSTOR

- Wolfe, Christopher. "Woodrow Wilson: Interpreting the Constitution," Review of Politics, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Jan., 1979), pp. 121–142 in JSTOR

- Woodward, Carl R. "Woodrow Wilson's Agricultural Philosophy," Agricultural History, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct., 1940), pp. 129–142 in JSTOR

Foreign policy

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E., “Woodrow Wilson and George W. Bush: Historical Comparisons of Ends and Means in Their Foreign Policies,” Diplomatic History, 30 (June 2006), 509–43.

- Bailey; Thomas A. Wilson and the Peacemakers: Combining Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace and Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1947)

- Clements, Kendrick, A. Woodrow Wilson: World Statesman (1999)

- Clements, Kendrick A. The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson (1992), covers foreign policy

- Clements, Kendrick A. "Woodrow Wilson and World War I," Presidential Studies Quarterly 34:1 (2004). pp 62+.

- Cooper, John Milton. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009), 720 pp.

- Davis, Donald E. and Eugene P. Trani; The First Cold War: The Legacy of Woodrow Wilson in U.S.-Soviet Relations (2002)

- Greene, Theodore P. ed. Wilson at Versailles (1957)

- Henderson, Peter V. N. "Woodrow Wilson, Victoriano Huerta, and the Recognition Issue in Mexico," The Americas, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Oct., 1984), pp. 151–176 in JSTOR

- Knock, Thomas J. To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order (1995)

- Kimitada, Miwa. "Japanese Opinions on Woodrow Wilson in War and Peace," Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 22, No. 3/4 (1967), pp. 368–389 in JSTOR

- Levin, Jr., N. Gordon Woodrow Wilson and World Politics: America's Response to War and Revolution (1968)

- Link, Arthur Stanley. Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910-1917 (1972) summarizes diplomatic history

- Link, Arthur S.; Wilson the Diplomatist: A Look at His Major Foreign Policies (1957)

- Link, Arthur S.; Woodrow Wilson and a Revolutionary World, 1913-1921 (1982)

- Magee, Malcolm D. What the World Should Be: Woodrow Wilson and the Crafting of a Faith-Based Foreign Policy (2008) excerpt and text search

- May, Ernest R. The World War and American Isolation, 1914-1917 (1959)

- Trani, Eugene P. “Woodrow Wilson and the Decision to Intervene in Russia: A Reconsideration.” Journal of Modern History (1976). 48:440—61. in JSTOR

- Walworth, Arthur. Wilson and His Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 online edition

Historiography

- Clements, Kendrick A. "The Papers of Woodrow Wilson and the Interpretation of the Wilson Era", The History Teacher, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Aug., 1994), pp. 475–489 in JSTOR

- Seltzer, Alan L. "Woodrow Wilson as 'Corporate-Liberal': Toward a Reconsideration of Left Revisionist Historiography," Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Jun., 1977), pp. 183–212 in JSTOR

- Steigerwald, David. The Reclamation of Woodrow Wilson? Diplomatic History; 1999 23(1): 79-99, on foreign policy in EBSCO; notes that New Left revisionism (by William Appleman Williams and N. Gordon Levin, Jr.) claiming that Wilson's Open Door was a facade for the imperialistic extension of American economic advantage, has faded away

- Watson, Jr., Richard L. "Woodrow Wilson and His Interpreters, 1947-1957," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Sep., 1957), pp. 207–236 in JSTOR, summarizes different interpretations as of 1957

- Extensive essay on Woodrow Wilson and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

Primary sources

- Pestritto, Ronald J. ed. Woodrow Wilson: The Essential Political Writings (2005)

- Link, Arthur S., ed. The Papers of Woodrow Wilson complete in 69 vol, at major academic libraries. Annotated edition of all of WW's letters, speeches and writings plus many letters written to him

- Tumulty, Joseph P. Woodrow Wilson as I Know Him (1921) memoir by chief of staff online edition

- Wilson, Woodrow. The New Freedom (1913) 1912 campaign speeches online edition

- Wilson, Woodrow. Why We Are at War (1917) six war messages to Congress, Jan- April 1917

- Wilson, Woodrow. Selected Literary & Political Papers & Addresses of Woodrow Wilson (3 vol 1918 and later editions)

- Wilson, Woodrow. Messages & Papers of Woodrow Wilson 2 vol (ISBN 1-135-19812-8)

- Wilson, Woodrow. The New Democracy. Presidential Messages, Addresses, and Other Papers (1913-1917) 2 vol 1926 (ISBN 0-89875-775-4)

- Wilson, Woodrow. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points (1918).

- full text of Wilson books and messages online

References

- ↑ http://home.comcast.net/~sharonday7/Presidents/AP060301.htm

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson: Big Government Anti-Catholic

- ↑ http://www.waragainsttheweak.com/

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n_KlDf-Wgoc

- ↑ In the 1880s Joseph Wilson argued at length that evolution was NOT in conflict with the Bible; he was thereupon forced out as head of the Presbyterian seminary in South Carolina. See Fred Kingsley Elder, Woodrow: Apostle of Freedom (1996) online review

- ↑ Francis P. Weisenburger, "The Middle Western Antecedents of Woodrow Wilson," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Dec., 1936), pp. 375-390 in JSTOR

- ↑ See White House biography of Ellen Louise Axson Wilson

- ↑ Edward S. Corwin, "Woodrow Wilson and the Presidency," Virginia Law Review, Vol. 42, No. 6 (Oct., 1956), pp. 761-783 in JSTOR. It was published in a journal edited by Henry Cabot Lodge, who became Wilson's bitter enemy in 1919.

- ↑ The Shaping of a Future President’s Economic Thought

- ↑ W. Barksdale Maynard, Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency (2008)

- ↑ Henry Wilkinson Bragdon, Woodrow Wilson: The Academic Years (1967)

- ↑ Yale and Harvard later did adopt the college model for undergraduates, but not Princeton. W. Barksdale Maynard, Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency (2008)

- ↑ he also wrote popular history of high quality, including a five-volume history of the United States and a life of George Washington.

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson and Harry Truman: Mission and Power in American Foreign Policy

- ↑ Scot J. Zentner, "President and Party in the Thought of Woodrow Wilson," Presidential Studies Quarterly; 1996 26(3): 666-677, in JSTOR

- ↑ Richard J. Stillman, II, "Woodrow Wilson and the Study of Administration: A New Look at an Old Essay," American Political Science Review, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Jun., 1973), pp. 582-588 in JSTOR; Larry Walker, "Woodrow Wilson, Progressive Reform, and Public Administration," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 104, No. 3 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 509-525 in JSTOR

- ↑ (2014) Colonel House: A Biography of Woodrow Wilson's Silent Partner. Oxford University Press, i-ii. ISBN 978-0195045505.

- ↑ (2002) Edith and Woodrow: The Wilson White House. Simon and Schuster, 398. ISBN 978-0743211581.

- ↑ (2006) Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House. Yale University, 7. ISBN 978-0300137552.

- ↑ (2014) Colonel House: A Biography of Woodrow Wilson's Silent Partner. Oxford University Press, 78. ISBN 978-0195045505.

- ↑ (1965) Woodrow Wilson. Houghton Mifflin Company, 288.

- ↑ (1922) The Letters of Franklin K. Lane, Personal and Political. Houghton Mifflin Company, 297.

- ↑ John S. Watterson, III, "Political Football: Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and the Gridiron Reform Movement," Presidential Studies Quarterly 1995 25(3): 555-564 in JSTOR

- ↑ Anthony Gaughan, "Woodrow Wilson and the Legacy of the Civil War," Civil War History 1997 43(3): 225-242; online in Questia; Gaughan, "Woodrow Wilson and the Rise of Militant Interventionism in the South," Journal of Southern History 1999 65(4): 771-808, in JSTOR

- ↑ Presidential Power: Unchecked and Unbalanced

- ↑ The Power of Tolerance: And Other Speeches, by George Brinton McClellan Harvey, pp. 174-178, For President: Woodrow Wilson, February 3rd, 1906

- ↑ Arthur S. S. Link, "Democratic Politics and the Presidential Campaign of 1912 in Tennessee," East Tennessee Historical Society's Publications 1979 51: 114-137

- ↑ Arthur S. Link, "The Baltimore Convention of 1912," American Historical Review 1945 50(4): 691-713 in JSTOR

- ↑ Nancy J. Weiss, "The Negro and the New Freedom: Fighting Wilsonian Segregation," Political Science Quarterly 1969 84(1): 61-79, in JSTOR

- ↑ Lewis L. Gould, Four Hats in the Ring: The 1912 Election and the Birth of Modern American Politics, (2008); Link (1947)

- ↑ American Nightmare: The History of Jim Crow, Jerrold M. Packard, St. Martin's Press, 2003, pp. 124-125

- ↑ https://www.nysun.com/national/princetons-purge-of-wilson-follows-a-change/91174/

- ↑ MJ Movie Reviews – Birth of a Nation, The (1915) by Dan DeVore Template:Webarchive

- ↑ Armstrong, Eric M. (February 26, 2010). Revered and Reviled: D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation'. The Moving Arts Film Journal.

You must specify archiveurl= and archivedate= when using {{cite web}}. Available parameters:

{{cite web |url = |title = |accessdate = |accessdaymonth = |accessmonthday = |accessyear = |author = |last = |first = |authorlink = |coauthors = |date = |year = |month = |format = |work = |publisher = |pages = |language = |doi = |archiveurl = |archivedate = |quote = }} - ↑ Stokes 2007, p. 111

- ↑ Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 page 421.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Franklin, John Hope "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History" pages 417–434 from The Massachusetts Review Volume 20, No. 3, Autumn 1979 page 430.

- ↑ Yellin, Eric S. (2013). Racism in the Nation's Service: Government Workers and the Color Line in Woodrow Wilson's America Template:Webarchive. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. p. 127. ISBN 9781469607207

- ↑ Hans Vought, . Division and Reunion: Woodrow Wilson, Immigration, and the Myth of American Unity. Journal of American Ethnic History; 1994 13(3): 24-50.

- ↑ James A. Sandos, "Pancho Villa and American Security: Woodrow Wilson's Mexican Diplomacy Reconsidered," Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Nov., 1981), pp. 293-311 in JSTOR

- ↑ Christine A. Lunardini, and Thomas J. Knock, Woodrow Wilson and Woman Suffrage: A New Look. Political Science Quarterly; 1980-1981 95(4): 655-671, in JSTOR

- ↑ Betty Miller Unterberger, "Woodrow Wilson and the Bolsheviks: the 'Acid Test' of Soviet-American Relations," Diplomatic History 1987, Vol. 11(2), pp.71-90.

- ↑ Frank W. Brecher, Woodrow Wilson and the Origins of the Arab-Israeli Conflict. American Jewish Archives; 1987 39(1): 23-47,

- ↑ The Hidden Agony of Woodrow Wilson

- ↑ 10 journos caught fabricating, Politico

- ↑ John Morton Blum, Woodrow Wilson and the Politics of Morality (1956); Richard M. Gamble, "Savior Nation: Woodrow Wilson and the Gospel of Service," Humanitas Volume: 14. Issue: 1. 2001. pp 4+; Cooper, Woodrow Wilson (2009) p 560.

- ↑ Arthur S. Link, "A Portrait of Wilson," Virginia Quarterly Review1956 32(4): 524-541

- ↑ John Morton Blum, Woodrow Wilson and the Politics of Morality (1956), p p10, 197-99

- ↑ David Steigerwald, Wilsonian Idealism in America (1994) p. 230.

- ↑ Arthur S. Link, ed. The Papers of Woodrow Wilson (1977) 23:20, speech on the Bible, in Denver May 7, 1911

- ↑ Josephus Daniels, The Life of Woodrow Wilson 1856-1924 (1924) p. 359

- ↑ Malcolm D. Magee, What the World Should Be: Woodrow Wilson and the Crafting of a Faith-Based Foreign Policy (2008)

- ↑ Eugene P. Trani, "Woodrow Wilson, China, and the Missionaries, 1913-1921," Journal of Presbyterian History 1971 49(4): 328-351,

- ↑ Madison Debates, June 7

- ↑ Madison Debates, June 8

- ↑ Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics, p. 9

- ↑ see Steigerwald,(1999)

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson and the Rejection of the Founders’ Constitution

- ↑ Hating Woodrow Wilson; The new and confused attacks on progressivism, What the new Woodrow Wilson haters don't understand

- ↑ The Mystery of Woodrow Wilson

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson: Godfather of Liberalism

- ↑ James A. Henretta, "Whose Government? Politics, Populists and Progressives, 1880-1917." In America: A Concise History, Volume Two: Since 1865, Volume 2, p. 622

- ↑ Speech at New York Press Club (9 September 1912), in The papers of Woodrow Wilson, 25:124

- ↑ Constitutional Government in the United States

- ↑ Paul M. Pearson and Philip M. Hicks, Extemporaneous Speaking (New York: Hinds, Noble & Eldredge, 1912), 177, printing Woodrow Wilson, “The Bible and Progress;” The Homiletic Review: An International Monthly Magazine of Current Religious Thought, Sermonic Literature and Discussion of Practical Issues (New York: Funk and Wagnalls Company, 1911), Vol. LXII, p. 238, printing Woodrow Wilson, “The Bible and Progress,” May 7, 1911.

External links

| |||||