Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a movement towards racial equality and an end to segregation of African Americans that occurred in the United States from about 1953 to 1968, as courts and Congress made segregation illegal and imposed strict laws attempting to ensure that blacks could be able to vote.

This term has been distorted in the 21st century, however, to mean special privileges for mostly wealthy LGBTQ persons, giving these predominantly white persons rights not available to everyone else. Transgenders have used "civil rights" to compete unfairly as biological males against females in sports.

Contents

GOP role in Civil Rights

The GOP always voted in higher percentages for civil rights bills from the 1860s when Republican Abraham Lincoln overturned slavery to the 1960s when the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act were passed.[1]

- 1863: Emancipation Proclamation, Executive Order by Republican President Abraham Lincoln freeing all slaves held within the rebellious states.

- 1865: 13th Amendment banning slavery passed by Republican President Abraham Lincoln with unanimous Republican support and most Democrats opposed.

- 1866: 14th Amendment giving due process and equal protection to all races passes with 100% of Democrats voting no in House and Senate.

- 1870: 15th Amendment giving all the right to vote regardless of race passes house with 98% Republican support and 97% Democrat opposition.

- 1875: Civil Rights Act of 1875 passed by Republican president U.S. Grant with 92% Republican support and 100% Democrat opposition.

- 1919: 19th Amendment Republican House passes the amendment giving women the right to vote, 85% of Republicans vote yes to 54% of Democrats and 80% of Republicans in Senate vote yes but nearly half of Democrats vote no.

- 1922 Anti-Lynching Law passed first time by Republican House; filibustered by Democrats in the Senate.

- 1924: Republican President Calvin Coolidge signs the law passed by Republican Congress giving Native Americans the right to vote.

- 1954: Brown v. Board of Education, Republican Chief Justice appointed by Republican President Dwight Eisenhower writes Supreme Court decision overturning previous Democrat Supreme Court "separate by equal" doctrine, outlawing school segregation.

- 1957: Republican President Dwight Eisenhower signs the Republican Party sponsored 1957 Civil Rights Act creating the Civil Rights Commission.

- 1957: Republican President Dwight Eisenhower order federal troops to take over Arkansas National Guard which Democrat Gov. Orval Faubus used to prevent black children to attend public school. Eisenhower ordered the 101st Airborne Division to escort the children passed protesters.

- 1964: Civil Rights Act ending segregation and voter restrictions is passed with 80% of Republicans in the House and 82% in the Senate voting yes, but only 63% of Democrats voting yes in the House and 69% in the Senate. Democrats filibustered for 83 days. After passing the Civil Rights Act, Democratic party president Lyndon B. Johnson brags "I'll have those n****** voting Democratic for the next 200 years."[2]

- 1965: Voting Rights Act passed to remove racial voter discriminations against blacks and Hispanics with 82% of Republicans voting yes to 78% of Democrats in the House, and 94% of Republicans in the Senate to 73% of Democrats in the Senate.

- 1973: Only 2 of the 112 Democrats who opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 actually switched to the Republican Party, John Jarman and Strom Thurmond. All the racist Democrats who had opposed the Civil Rights Act in the 1960s were the same ones who in the 1970s supported Roe v. Wade. They went straight from supporting segregation to supporting abortion.

Reconstruction

During Reconstruction, Radical Republicans tried to guarantee equal rights for emancipated slaves after the American Civil War. They succeeded in passing the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendment, which in theory required equal protection of the laws and an equal right to vote.

Democrat reaction

The Republican coalition in the South fell apart in the 1870s, and conservative white Redeemers took control. The Redeemers were paternalistic toward blacks but they confronted a Populist element in the 1890s that demanded strict segregation, called Jim Crow.

The Supreme Court allowed segregation in 1896, and black leaders such as Booker T. Washington worked to build an alliance of black businessmen and farmers with benevolent whites, using education as the tool to eventually achieve equality. Militant blacks led by W.E.B. DuBois and the NAACP demanded immediate redress. For a brief while around 1920 militant black separatists gained strength. While blacks slowly improved their economic status in the South in the 20th century, despite lynchings, they remained second class citizens with very little political power. Blacks began moving in large numbers to the North to meet the labor shortages during World War I and World War II. By the 1950s they had a political base in Harlem (New York City) and Chicago, but still very little power. Jim Crow remained as strong as ever in the South, where white Democrats had near-total control.

1954-1968 movement

Presidents Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson became proactive in the Civil Rights movement.

In the late 1960s several southern states expressed forceful opposition to what was considered Federal tyranny; some redesigned their state flags to include the old Confederate banner. In 1962, the prospect of a black student being admitted to the University of Mississippi resulted in campus riots suppressed by Federal troops and a national guard now brought under Federal control.

Brown v. Board of Education

The election of a Republican for the first time in 20 years was momentous. Eisenhower appointed Republican California Governor Earl Warren as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. All the other members had been appointed by Roosevelt and Truman who believed courts should defer to the policymaking prerogatives of the White House and Congress. Warren convened a meeting of the justices and presented to them the simple argument that the only reason to sustain segregation was a deep-rooted belief in the inferiority of African-Americans. in Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, Warren produced a unanimous decision that said:"Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group…Any language in contrary to this finding is rejected. We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”The Southern Manifesto was a document issued in response to the Supreme Court 1954 ruling Brown v. Board of Education, which integrated public schools. It was signed by 101 members of Congress from the former Confederate States - 99 Democrats and 2 Republicans. John Sparkman the 1952 Vice Presidential candidate as part of the Democrat's Southern Strategy, J. William Fulbright mentor of Bill Clinton, Richard Russell of the Warren Commission, Sam Ervin of the Watergate Committee, Hale Boggs, the father of NPR's Cokie Roberts, and Wilbur Mills were all signatories. It reads in part:

"This unwarranted exercise of power by the Court, contrary to the Constitution, is creating chaos and confusion in the States principally affected. It is destroying the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through 90 years of patient effort by the good people of both races. It has planted hatred and suspicion where there has been heretofore friendship and understanding....We commend the motives of those States which have declared the intention to resist forced integration by any lawful means."

Little Rock Nine

One of the first challenges to Brown v. Board of Education was when Democrat Gov. Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to prevent African-American students from enrolling at Little Rock Central High School. Central High was an all-white school. Faubus ordered the troops to "accomplish the mission of maintaining or restoring law and order and to preserve the peace, health, safety and security of the citizens." A force of 289 soldiers was assembled. The commander told nine black students, 6 girls and 3 boys ages 15–17 years old who were attempting to enter the school, to return home. The standoff continued for three weeks. Little Rock Democrat mayor Woodrow Wilson Mann appealed to President Eisenhower to help end the deadlock. Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne Division to federalized the entire 10,000-member Arkansas National Guard. The students were allowed to enroll.

Faubus was re-elected in 1958 with 82.5% of the vote over a Republican challenger. Faubus ordered the closure of four public high schools that year, preventing both black and white students from attending school while seeking a two and a half year delay on de-segregation until January 1961 in Federal Court when there would be a possibility of a Democratic president.

Montgomery Bus boycott

In early 1956, Martin Luther King, Jr. led the nonviolent boycott of city buses of Montgomery, Alabama, after he sent Rosa Parks to be arrested for not moving to the back of the bus.[3]

Parks refused to give up her seat to a white passenger, was arrested, convicted of disorderly conduct and fined $14.[4] This arrest led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott that lasted over a year, and culminated in the reversal of the seating policy. The incident is a landmark event in the Civil Rights movement.

1957 Civil Rights Act

Republican Attorney General Herbert Brownell originally proposed the Civil Rights Act of 1957. Vice President Richard Nixon invited Dr. King to the White House for a meeting on 13 June 1957. This meeting, described by Bayard Rustin as a “summit conference,” marked national recognition of King's role in the civil rights movement (Rustin, 13 June 1957). Seeking support for a voter registration initiative in the South, King appealed to Nixon to urge Republicans in Congress to pass the 1957 Civil Rights Act and to visit the South to express support for civil rights. Optimistic about Nixon's commitment to improving race relations in the United States, King told Nixon, “How deeply grateful all people of goodwill are to you for your assiduous labor and dauntless courage in seeking to make the civil rights bill a reality.”

Democrat Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson had Judiciary chairman Sen. James Eastland drastically water-down the House version, removing stringent voting protection clauses.[5][6] The bill passed 285–126 in the House with Republicans providing the majority of votes 167–19 and Democrats 118–107.[7] It then passed 72–18 in the Senate, with Republicans again supplying the majority of votes, 43–0 and Democrats voting 29–18. Sen. John F. Kennedy voted for the jury trial amendment which weakened Title IV, rendering the bill toothless.[8] It was the first federal civil rights legislation passed by the United States Congress since the Republicans passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Johnson told Sen. Richard Russell,"These Negroes, they're getting pretty uppity these days and that's a problem for us since they've got something now they never had before, the political pull to back up their uppityness. Now we've got to do something about this, we've got to give them a little something, just enough to quiet them down, not enough to make a difference. For if we don't move at all, then their allies will line up against us and there'll be no way of stopping them, we'll lose the filibuster and there'll be no way of putting a brake on all sorts of wild legislation. It'll be Reconstruction all over again."[9]

Sit-ins

The Civil Rights Movement received an infusion of energy when students in Greensboro, North Carolina; Nashville, Tennessee; and Atlanta, Georgia, began to "sit-in" at the lunch counters of a few of their local stores, to protest those establishments' refusal to desegregate. These protesters were encouraged to dress professionally, to sit quietly, and to occupy every other stool so that potential white sympathizers could join in. Many of these sit-ins provoked local authority figures to use brute force in physically escorting the demonstrators from the lunch facilities.

The "sit-in" technique was not new - the Congress of Racial Equality had used it to protest segregation in the Midwest in the 1940s - but it brought national attention to the movement in 1960. The success of the Greensboro sit-in led to a rash of student campaigns throughout the South. Probably the best organized, most highly disciplined, the most immediately effective of these was in Nashville, Tennessee. By the end of 1960, the sit-ins had spread to every Southern and border state and even to Nevada, Illinois, and Ohio. Demonstrators focused not only on lunch counters but also on parks, beaches, libraries, theaters, museums, and other public places. Upon being arrested, student demonstrators made "jail-no-bail" pledges, to call attention to their cause and to reverse the cost of protest, thereby saddling their jailers with the financial burden of prison space and food.

The Kennedy's

Robert Kennedy, who managed the Kennedy for President campaign, opposed the outreach to Black voters and sided with traditional Southern racists of the New Deal coalition.[10] Bobby Kennedy was furious with campaign aides for talking with Dr. King, and felt it would cost them the 1960 election.

King served as honorary president of the "Gandhi Society for Human Rights." He was displeased with the pace that President Kennedy was using to address the issue of segregation. In 1962, King and the Gandhi Society produced a document that called on the President to follow in the footsteps of Abraham Lincoln and issue an executive order to deliver a blow for civil rights as a kind of Second Emancipation Proclamation. Kennedy did not execute the order.[11]

Bayard Rustin's open homosexuality, support of democratic socialism, and his ties to the Communist Party USA caused many white and African-American leaders to demand King distance himself from Rustin,[12] which King agreed to do. However, Rustin did collaborate in the 1963 March on Washington, for which Rustin was the primary logistical and strategic organizer.[13][14]

Great Society

Johnson in built a coalition that included white churches, Jews, and labor unions, as well as many Republicans such as Everett Dirksen, to build a majority of the northern leadership in favor of action. The Democratic South filibustered but failed stop passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended Jim Crow, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which guaranteed federal oversight of voting rights.

Mississippi Freedom Party

The Mississippi Freedom Party was organized by African Americans to challenge the establishment Democratic Party, which allowed participation only by whites. The party ran a slate of delegates with close to 80,000 people casting ballots.[16] The party hoped to replace the Regular Democrats as the official Mississippi delegation at the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

At the convention the party challenged the Regular Democrats' right to be seated, claiming that the Regular Democrats were illegally elected in a segregated process that violated both party regulations and federal law.[17] The Equal Protection Clause had been on the books for nearly 100 years already. The Democratic Party referred the challenge to the credentials committee,[18] which televised its proceedings and allowed the nation to see and hear the moving testimony of several delegates and the retaliation inflicted on them by Democrats for attempting to vote.[19]

After that, most observers and pundits thought the credentials committee were ready to unseat the Regular Democrats and seat the Freedom Party delegates in their place. But some Democrats from other states threatened to leave the convention and bolt the party if the Regular Democrats were unseated. President Johnson wanted a united convention and feared losing support. To ensure his victory in November, Johnson maneuvered to prevent the Mississippi Freedom Democrats from replacing the all-white Regular Democrats.

Two future Democrat Presidential nominees, Hubert Humphrey and Walter Mondale, denied Blacks equal protection and made a mockery of the civil rights movement.[20] Johnson held a private meeting with Humphrey, Mondale, Roy Wilkins, Andrew Young, United Auto Workers President Walter Reuther and Martin Luther King Jr. A plan was hatched to offer the Freedom Democrats two non-voting At-Large seats with observer status, rather than replace the all-white delegation which had been undemocratically and illegally elected.[21] Johnson arrogated to himself the right to pick which two, and Johnson chose one white and one black. Johnson dispatched Humphrey and Mondale and ordered them to make sure that “that illiterate woman," Fannie Lou Hamer would never be a delegate. Dr. King protested and was told by Reuther to shut up.

The offer was rejected, but Humphrey and Mondale remained powerhouse liberals in the Democratic party for another 20 years.

1964 Civil Rights Act

President Johnson finally signed the bi-partisan Civil Rights Act of 1964, which he called "the N****r Bill."[22] In lobbying fellow Democrats for the bill, Johnson said,"I'll have them n*gg*rs voting Democratic for two hundred years."[23]Democrats tried to block passage by filibustering for 75 hours, including a 14-hour and 13-minute speech by the Exalted Cyclops Sen. Robert Byrd, who later became Senate Democrat Leader in the Reagan era.[24] The law was intended to block Republican gains in the South and buy off Blacks with affirmative action programs.

1965 Voting Rights Act

- See also: Voting Rights Act of 1965

Affirmative Action

- See also: Affirmative Action

Biden era

- See also: Civil Rights in the Biden era

Under the leadership of Senator and later Democrat president Joseph Biden, the civil rights movement suffered many heartbreaking setbacks. Beginning with Biden's attack on school desegregation and the Civil Rights Act of 1965, later the mass incarceration of a generation of American American youth, and as president, the setting up of concentration camps for immigrant children,[25] Biden re-established what many consider the Democrat party's birthright to dominate and control minorities.

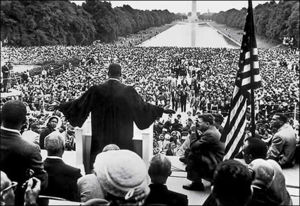

Leaders

Black leaders claimed that their own efforts were more important in causing change, emphasizing activities like bus boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins. A black Baptist minister from Atlanta Martin Luther King led the new movement. Painstaking work by labor unions, civil rights groups, and mainstream churches, aided by popular outrage at the violent techniques used by police in some southern cities fueled a national consensus that segregated and second class status had to end. Some of the organizations that spearheaded the movement were the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, or 'Snick'), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the older National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). All were committed to non-violence and Gandhian civil disobedience in the early years, a tactic that was politically essential in order to win public support and to avoid alienating northern voters.

Black Leaders

Non-black supporters

Black Power

Nation of Islam

Meanwhile, a growing black radical movement, led by Muslims like Malcolm X, and inner city gangs, pulled the black community toward separatism. By 1966 the tensions inside the black community were ripping apart the civil rights coalition, as the radicals called for the ousting of all whites in leadership positions. King lost much of his influence, and was unable to stop the wave of rioting that broke out in every major American city with a black population. The riots soured white America on the civil rights movement because it brought violence and turmoil, and led to calls for Law and order.

Malcolm X described collaboration with white liberals this way:"The white Liberal differs from the white Conservative only in one way; the Liberal is more deceitful, more hypocritical, than the Conservative. Both want power, but the White Liberal is the one who has perfected the art of posing as the Negro's friend and benefactor and by winning the friendship and support of the Negro, the White Liberal is able to use the Negro as a pawn or a weapon in this political football game, that is constantly raging, between the White Liberals and the White Conservatives. The American Negro is nothing, but a political "football game" that is constantly raging between the white liberals and white conservatives.[26]

Black Panthers

In 1968, two years after the Black Panthers' founding, the organization counted four hundred members, mainly from the poor parts of Oakland. When Martin Luther King died, membership grew to five thousand with over 45 chapters and branches. The organization also published a newspaper which by 1969 circulated to over 250,000 subscribers.

Co-opted by feminists and gays

The legislative victories won by a racial minority were later co-opted by other groups, notably feminists in the name of "women's rights" (women are not a minority and constitute 51% of the population), and homosexuals, who are not a minority by birth but rather by choice.

See also

- Constance Baker Motley

- James B. Parsons

- Bill of Rights

- United States Constitution

- Black history

- Black Americans, history and religion

Further reading

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63 (1988)

- Graham, Hugh Davis. Civil Rights in the United States (1994)

- Graham, Hugh Davis. The Civil Rights Era: Origins and Development of National Policy, 1960-1972 (1990)

- Horton, James Oliver and Horton, Lois E. Hard Road to Freedom: The Story of African America. (2001). 405 pp. by leading black historians

- Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and its Troubled Legacy. (2001). 285 pp.

- Riches, William T. Martin. The Civil Rights Movement: Struggle and Resistance. (1997). 196 pp.

- Thernstrom, Stephan and Thernstrom, Abigail. America in Black and White: One Nation, Indivisible. (1997). 704 pp. by leading conservative scholars

- Verney, Kevern. Black Civil Rights in America. (2000). 135 pp.

Primary sources

- Birnbaum, Jonathan and Taylor, Clarence, eds. Civil Rights since 1787: A Reader on the Black Struggle. (2000). 935 pp.

- D'Angelo, Raymond, ed. The American Civil Rights Movement: Readings and Interpretations. (2001). 592 pp.

References

- ↑ Parks, B. The Democrat Race Lie. BlackAndRight.com.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:United_States_federal_civil_rights_legislation - ↑ The Relentless Conservative (2011, August 24). The Democratic Party's Two-Facedness of Race Relations. The Huffington Post.

- ↑ http://www.thekingcenter.org/mlk/chronology.html

- ↑ https://www.cnn.com/2005/US/10/24/parks.obit/

- ↑ https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1951-2000/The-Civil-Rights-Act-of-1957/

- ↑ Caro, Robert, Master of the Senate: The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Chapter 39

- ↑ HR 6127. CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1957. PASSED. YEA SUPPORTS PRESIDENT'S POSITION. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/85-1957/h42

- ↑ August 2, 1957. HR. 6127. CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1957. AMENDMENT TO GUARANTEE JURY TRIALS IN ALL CASES OF CRIMINAL CONTEMPT AND PROVIDE UNIFORM METHODS FOR SELECTING FEDERAL COURT JURIES. GovTrack.us. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ↑ Said to Senator Richard Russell, Jr. (D-GA) regarding the Civil Rights Act of 1957. As quoted in Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream (1977), by Doris Kearns Goodwin, New York: New American Library, p. 155.

- ↑ Jack Kennedy: Elusive Hero, Chris Matthews, Simon and Schuster, Nov 6, 2012, p. 309.

- ↑ Martin Luther King Jr. and the Global Freedom Struggle: Gandhi Society for Human Rights. Stanford University.

- ↑ Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513674-8.

- ↑ De Leon, David (1994). Leaders from the 1960s: A biographical sourcebook of American activism. Greenwood Publishing, 138–143. ISBN 0-313-27414-2.

- ↑ Cashman, Sean Dennis (1991). African-Americans and the Quest for Civil Rights, 1900–1990. NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-1441-2.

- ↑ Fannie Lou Hamer's Powerful Testimony, American Experience, PBS. youtube.

- ↑ Freedom Ballot in MS ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ↑ The Mississippi Movement & the MFDP ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ↑ Branch, Taylor (1998). Pillar of Fire. Simon & Schuster.

- ↑ Carmichael, Stokely, and Charles V. Hamilton. Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, (New York: Random House, 1967), p. 90.

- ↑ https://www.minnpost.com/eric-black-ink/2011/05/sad-story-humphreys-role-1964-democratic-convention/

- ↑ Mills, Kay, This Little Light of Mine: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer, (New York: Plume, 1994), p. 5.

- ↑ http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/lyndon-johnson-civil-rights-racism

- ↑ Said to two governors regarding the Civil Rights Act of 1964, according to then-Air Force One steward Robert MacMillan as quoted in Inside the White House (1996), by Ronald Kessler, New York: Simon and Schuster, p. 33.

- ↑ Civil Rights Filibuster Ended. Art & History Historical Minutes. United States Senate.

- ↑ https://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/297967

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7YmjWW9tx4