Difference between revisions of "Robert Taft"

(→Political career: Taft was not Senate Majority Leader until 1953.) (Tags: Mobile edit, Mobile web edit) |

(Fixed.) (Tags: Mobile edit, Mobile web edit) |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

}} | }} | ||

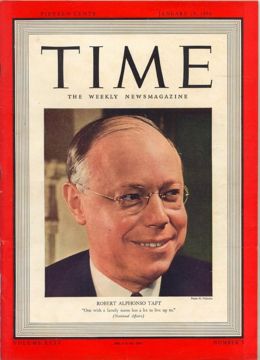

[[File:Taft40.jpg|thumb|260px|''Time'' Jan. 29, 1940]] | [[File:Taft40.jpg|thumb|260px|''Time'' Jan. 29, 1940]] | ||

| − | '''Robert Alphonso Taft, Sr.''' (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953), son of President [[William Howard Taft]], was a leading Republican Senator (1938–53) and known as "Mr. Republican". He was a leader of the [[Conservative Coalition]], working with other Northern Republicans and some Southern Democrats to control Congress on most domestic issues (aside from [[civil rights]], which the conservative Republicans supported while the | + | '''Robert Alphonso Taft, Sr.''' (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953), son of President [[William Howard Taft]], was a leading Republican Senator (1938–53) and known as "Mr. Republican". He was a leader of the [[Conservative Coalition]], working with other Northern Republicans and some Southern Democrats to control Congress on most domestic issues (aside from [[civil rights]], which the conservative Republicans supported while the Southern Democrats opposed). Little major legislation passed the Senate against his objections. |

His crowning achievement was writing and passing the [[Taft-Hartley Act]] of 1947 over [[President Truman]]'s veto. It balanced the interests of unions, management and the public. | His crowning achievement was writing and passing the [[Taft-Hartley Act]] of 1947 over [[President Truman]]'s veto. It balanced the interests of unions, management and the public. | ||

Latest revision as of 15:39, May 8, 2024

| Robert Alphonso Taft, Sr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Former Senate Majority Leader From: January 3, 1953 – July 31, 1953 | |||

| Predecessor | Ernest McFarland | ||

| Successor | William F. Knowland | ||

| Former U.S. Senator from Ohio From: January 3, 1939 – July 31, 1953 | |||

| Predecessor | Robert J. Bulkey | ||

| Successor | Robert A. Burke | ||

| Former State Senator from Ohio From: 1931–1933 | |||

| Predecessor | ??? | ||

| Successor | ??? | ||

| Former Speaker of the Ohio House of Representatives From: January 15, 1926 – January 2, 1927 | |||

| Predecessor | Harry D. Silver | ||

| Successor | O. C. Gray | ||

| Former State Representative from Ohio From: 1921–1931 | |||

| Predecessor | ??? | ||

| Successor | ??? | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Republican | ||

| Spouse(s) | Martha Wheaton Bowers | ||

| Religion | Episcopalian | ||

Robert Alphonso Taft, Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953), son of President William Howard Taft, was a leading Republican Senator (1938–53) and known as "Mr. Republican". He was a leader of the Conservative Coalition, working with other Northern Republicans and some Southern Democrats to control Congress on most domestic issues (aside from civil rights, which the conservative Republicans supported while the Southern Democrats opposed). Little major legislation passed the Senate against his objections.

His crowning achievement was writing and passing the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 over President Truman's veto. It balanced the interests of unions, management and the public.

Contents

Background

Taft was the scion of a powerful Republican family based in Cincinnati, Ohio. His father was elected president in 1908, and in 1921 became Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Taft's sister Helen Taft Manning was a professor, and his brother Charles Taft was a leading reformer in Cincinnati. As a boy he spent three years in the Philippines, where his father was governor.

Known throughout his life for his brilliant grasp of complexity, he was first in his class at the Taft School (run by his uncle), at Yale College (1910) and at Harvard Law School (1913), where he edited the Harvard Law Review. He practiced law with the firm of Maxwell and Ramsey in Cincinnati, Ohio. On Oct. 17, 1914, he married Martha Wheaton Bowers, the daughter of Lloyd Bowers, who had served as his father's solicitor general.

Taft confessed in 1922 that "while I have no difficulty talking, I don't know how to do any of the eloquence business which makes for enthusiasm or applause".[1] Taft himself appeared taciturn and coldly intellectual, characteristics that were offset by his gregarious wife, who served the same role his mother had for his father, as a confident and powerful asset to her husband's political career. They had four sons. Robert Alphonso Taft, Jr., served as a senator from Ohio. Horace Dwight Taft, became a professor of physics and dean at Yale. William Howard III served as ambassador to Ireland.

Political career

Rejected by the army for poor eyesight, in 1917 he joined the legal staff of the Food and Drug Administration where he met Herbert Hoover who became his idol. In 1918–19 he was in Paris as legal adviser for the American Relief Administration, Hoover's agency which distributed food to war-torn Europe. He learned to distrust governmental bureaucracy as inefficient and detrimental to the rights of the individual, principles he promoted throughout his career. He distrusted the League of Nations, and European politicians generally. He strongly endorsed the idea of a powerful World Court that would enforce international law, but no such idealized court ever existed. He returned to Ohio in late 1919, promoted Hoover for president, and opened a law firm with his brother Charles Phelps Taft II.

In 1920 he was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives, where he served as Speaker of the House in 1926. In 1930 he was elected to the State Senate, but was defeated for reelection in 1932. As an efficiency-oriented progressive, he worked to modernize the state's antiquated tax laws and supported mildly progressive legislation, such as limitations on child labor.

He was an outspoken opponent of the Ku Klux Klan and supportive of civil rights, backing anti-lynching legislation, an end to the poll tax, and desegregation in the U.S. military.[2] Taft particularly believed in a conservative-oriented approach to ensuring equality and tried to pass "voluntary FEPC" legislation, which ultimately was defeated by a Senate filibuster.[3] Throughout the 1920s and 1930s he was a powerful figure in local and state political and legal circles, and was known as a loyal Republican who never threatened to bolt the party.

Cartoonists loved his rimless spectacles and moonlike face, portraying him something like a grapefruit with eyeglasses. Taft was a boring poor speaker and did not mix well, but his total grasp of the complex details of every issue impressed reporters and politicians. (Democrats joked that "Taft has the best mind in Washington, until he makes it up.") His fans were strongly dedicated to him, while his enemies feared him as the strongest force in Congress.

In the 1930s, he practiced law, giving speeches critical of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. However he supported some of its programs as collective bargaining, stock exchange regulation, minimum wages, old-age pensions, and unemployment insurance.

U.S. Senate

| |

Taft was elected to the first of his three terms as U.S. Senator in the Republican landslide of 1938.[4] The expansion of the New Deal had been stopped and Taft saw his mission to roll it back, bringing efficiency to government and letting business restore the economy. He proclaimed that the New Deal was "socialistic" as he attacked deficit spending, high farm subsidies, governmental bureaucracy, and the National Labor Relations Board. He did support Social Security and public housing, while attacking federal health insurance. Taft orchestrated the Conservative Coalition, which had effective control of Congress from 1939 to the early 1960s. Taft set forth a conservative program oriented toward economic growth, individual economic opportunity, adequate social welfare, strong national defense, and non-involvement in European wars.

Taft was re-elected again in 1944 and in 1950, after high-profile contests battling the labor unions in an industrial state. He continued to grow in power after the GOP swept the elections of 1946, though he left foreign policy to his colleague Sen. Arthur Vandenberg.

Moving a bit to the left in the late 1940s, he supported federal aid to education (which did not pass). He cosponsored the Taft-Wagner-Ellender Housing Act to subsidize public housing in inner cities. Government, he argued in 1946, should "give to all a minimum standard of living," including sufficient education to give "to all children a fair opportunity to get a start in life."[5]

Labor issues

The Taft-Hartley Act single-handedly ended a growing problem of strikes after World War II, and preserved capitalism in the United States. Ever since, Democrats have sought unsuccessfully for its repeal. It bans "unfair" union practices, outlaws closed shops, and authorizes the President to seek federal court injunctions to impose an eighty-day cooling-off period if a strike threatened the national interest.

Foreign policy

During 1939 to 1941 Taft was strongly opposed American entry into World War II, while supporting military mobilization and limited aid to Britain. He fully endorsed the America First Committee, arguing in January 1941 that "Hitler's defeat is not vital to us."[6]

After Pearl Harbor (Dec. 1941), however, he completely supported an all-out war against Germany and Japan. The war itself, Taft always argued, was being fought to "make clear that national aggression cannot succeed in this world",[7] and not as liberals said to advance the Four Freedoms, the Atlantic Charter, or publisher Henry Luce's "American Century."

In 1945 Taft found the new United Nations Charter sacrificed "law and justice" to "force and expediency." he lost some popularity when he stated that the Nuremberg trials were based on faulty ex post facto statutes; that position earned him a chapter in Senator John F. Kennedy's famous book, Profiles in Courage (1958).

In the late 1940s, Taft did not view Stalin's Soviet Union as a major threat. Nor did he pay much attention to internal Communism. The true danger he said was big government and runaway spending. He supported the Truman Doctrine, reluctantly approved the Marshall Plan but tried to cut its budget, and opposed NATO as unnecessary and provocative. In 1950-52 he took the lead condemning President Harry S. Truman's handling of the Korean War. Taft tolerated Senator Joseph McCarthy's attacks on Democrats, claimed President Truman was fostering a "police state," and blamed General George C. Marshall for the loss of China and the subsequent Korean War.

Berger (1967) rejected the liberal criticism of Taft as an "isolationist", which is a pejorative term used by the Left to smear opponents of globalism. Berger says Taft was rather a "conservative nationalist at odds with the struggling attempts of liberal American policy-makers to fashion a program in the postwar years." Taft profoundly believed in the exceptionalism of America and its people, and argued the "principal purpose of the foreign policy of the United States is to maintain the liberty of our people." Taft identified three fundamental requirements for the maintenance of American liberty-an economic system based on free enterprise, a political system based on democracy, and national independence and sovereignty. All three, he feared, might be destroyed in a war, or even by extensive preparations for war, so he did not see Stalin's Soviet Union as a major threat to American values. Nor did he pay much attention to internal Communism. The true danger he said was big government and runaway spending. He supported the Truman Doctrine, reluctantly approved the Marshall Plan, and opposed NATO as unnecessary and provocative. He consistently opposed the draft and took the lead condemning President Harry S. Truman's handling of the Korean War.[8]

Presidential ambitions

Taft sought the GOP nomination in 1948 but it went to his arch-rival, Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York. One reason was Taft's reluctance to support farm subsidies, a position that hurt his party in the farm belt. Taft relied on a national core of loyalists, but had trouble breaking through to independents, and hated to raise money.

Taft tried again in 1952, using a strong party base. According to conservative GOP congressman B. Carroll Reece of Tennessee's 1st congressional district, he had the solid support from the GOP delegations of southern and border states.[9] Indeed, "black and tan" delegations,[10] including the Mississippi group led by Perry Wilbon Howard, II,[11] supported the strongly pro-civil rights Taft over Moderate Republican Dwight Eisenhower for the GOP nomination.

Taft also promised his supporters that he would name Douglas MacArthur as candidate for Vice President, but was defeated by charismatic Eisenhower. Conservatives felt that chicanery by his opponents caused his narrow defeat at the Republican National Convention. To gain Taft's support in the campaign, Eisenhower promised he would take no reprisals against Taft partisans, would cut federal spending, and would fight "creeping socialism in every domestic field." All along Eisenhower agreed with Taft on most domestic issues; their dramatic difference was in foreign policy. Eisenhower firmly believed in NATO and committed the U.S. to an active anti-Communist foreign policy.

His death was untimely, succumbing to cancer only six months after becoming the Senate Majority Leader in 1953. He is honored with a special monument on Capitol Hill, and was selected in 1959 by senators as one of the five most significant senators in history.

See also

- Hugh A. Butler, former U.S. senator from Nebraska

- William M. McCulloch, former U.S. representative from Ohio's 4th district

- Howard Buffett, former U.S. representative from Nebraska's 2nd district

Bibliography

- Armstrong John P. "The Enigma of Senator Taft and American Foreign Policy." Review of Politics 17:2 (1955): 206-231. in JSTOR

- Berger Henry. "A Conservative Critique of Containment: Senator Taft on the Early Cold War Program." In David Horowitz, ed., Containment and Revolution. (1967), pp 132–39

- Berger, Henry. "Senator Robert A. Taft Dissents from Military Escalation." In Thomas G. Paterson, ed., Cold War Critics: Alternatives to American Foreign Policy in the Truman Years. (1971)

- Doenecke, Justus D. Not to the Swift: The Old Isolationists in the Cold War Era (1979), by a conservative historian

- Kirk, Russell, and James McClellan. The Political Principles of Robert A. Taft (1967), by a leading conservative

- Malsberger, John W. From Obstruction to Moderation: The Transformation of Senate Conservatism, 1938-1952 (2000)

- Matthews, Geoffrey. "Robert A. Taft, the Constitution, and American Foreign Policy, 1939-53," Journal of Contemporary History, 17 (July, 1982),

- Moore, John Robert. "The Conservative Coalition in the United States Senate, 1942-45." Journal of Southern History 1967 33(3): 369-376. uses roll calls in JSTOR

- Moser, John E. "Principles Without Program: Senator Robert A. Taft and American Foreign Policy," Ohio History (1999) 108#2 pp 177–92 online edition, by a conservative historian

- Patterson, James T. "A Conservative Coalition Forms in Congress, 1933-1939," The Journal of American History, Vol. 52, No. 4. (Mar., 1966), pp. 757–772. in JSTOR

- Patterson, James T. Congressional Conservatism and the New Deal: The Growth of the Conservative Coalition in Congress, 1933-39 (1967)

- Patterson, James T. Mr. Republican: A Biography of Robert A. Taft (1972), standard scholarly biography

- Radosh. Ronald. Prophets on the right: Profiles of conservative critics of American globalism (1978)

- Pietrusza, David 1948: Harry Truman's Improbable Victory and the Year that Changed America, New York: Union Square Press, 2011.

- Reinhard, David W. The Republican Right since 1945 1983 online edition

- Van Dyke, Vernon, and Edward Lane Davis. "Senator Taft and American Security." Journal of Politics 14 (1952): 177-202. online edition

- White; William S. The Taft Story (1954). Pulitzer prize online edition

- Wunderlin, Clarence E. Robert A Taft: Ideas, Tradition, And Party In U.S. Foreign Policy (2005).

Primary sources

- Kirk, Russell and James McClellan, eds. The Political Principles of Robert A. Taft (1967).

- Wunderlin, Clarence E. Jr., et al. eds. The Papers of Robert A. Taft vol 1, 1889-1939 (1998); vol 2; 1940-1944 (2001); vol 3 1945-1948 (2003) online edition; vol 4, 1949-1953 (2006).

notes

- ↑ Taft Papers 1:271

- ↑ Edwards, Lee (October 29, 2020). The Political Thought of Robert A. Taft. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ↑ Robert Taft’s Conservative Proposal for Civil Rights. fascinatingpolitics.com. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ↑ OH US Senate Race - Nov 08, 1938. Our Campaigns. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ↑ Taft, Papers 3:111

- ↑ Taft, Papers 2:218

- ↑ Taft, Papers 2:443

- ↑ See John Moser, "Principles Without Program: Senator Robert A. Taft and American Foreign Policy," Ohio History, (1999) 108#2 pp. 177-192.

- ↑ December 17, 1951. G.O.P. IN SOUTH SOLID FOR TAFT, SAYS REECE. The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ Rothbard, Murray N. (June 21, 2011). Swan Song of the Old Right. Mises Institute. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ Apple, Jr., R.W. (August 31, 2004). THE REPUBLICANS: THE CONVENTION IN NEW YORK -- APPLE'S ALMANAC; Father of the Southern Strategy, at 76, Is Here for His 11th Convention. The New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

- Old Right

- Conservatism

- Ohio

- Former United States Senators

- Republican Party

- Great Depression

- United States History

- New Deal

- Conservatives

- Patriots

- Civil Rights

- Nationalism

- State Representatives

- State Senators

- Republican Anti-establishment

- Non-Interventionist Republicans

- Movement Conservatives

- Best Conservative Politicians