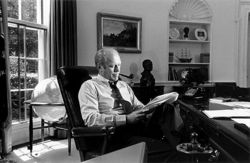

Gerald Ford

| Gerald Rudolph Ford, Jr. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 38th President of the United States From: August 9, 1974 – January 20, 1977 | |||

| Vice President | Nelson Rockefeller | ||

| Predecessor | Richard Nixon | ||

| Successor | Jimmy Carter | ||

| 40th Vice President of the United States From: December 6, 1973 – August 9, 1974 | |||

| President | Richard Nixon | ||

| Predecessor | Spiro Agnew | ||

| Successor | Nelson Rockefeller | ||

| Former U.S. Representative from Michigan's 5th Congressional District From: January 3, 1949 – December 6, 1973 | |||

| Predecessor | Bartel J. Jonkman | ||

| Successor | Richard F. Vander Veen | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Republican | ||

| Spouse(s) | Betty Ford | ||

| Religion | Episcopalian | ||

Gerald Rudolph “Jerry” Ford, Jr. (b. Leslie Lynch King, Jr., July 14, 1913 – December 26, 2006) was the 38th President of the United States of America, serving from August 9, 1974, to January 20, 1977. He was the first president not elected to either the presidency or vice-presidency. A Republican, Ford served as U.S. Representative, 1948–73, and was the House Minority Leader from 1965 to 1973. His most famous and daring decision was to pardon former President Richard Nixon of any crimes for the good of the nation. Nixon appointed Ford as Vice President on the resignation of Spiro Agnew. When Nixon subsequently resigned as President, Ford succeeded him.

President Ford received heavy criticism for pardoning Nixon. Ford watched helplessly as South Vietnam fell to a Communist invasion, after all American forces had been removed. He promoted détente with the Soviet Union, incurring the wrath of the conservatives, led by Ronald Reagan. He narrowly defeated Reagan for renomination in 1976 in the Republican Party primaries, then lost narrowly to Democrat Jimmy Carter.

Ford was pro-business and a local activist, and was known as a decent person and good family man; in his three years in office, he did much to heal the deep national wounds he had inherited from Nixon.

However, Ford nominated John Paul Stevens to the Supreme Court – Stevens became one of its most left-wing justices.[1]

Contents

Early life

Ford was born on July 14, 1913, in Omaha, Nebraska, and was named Leslie King after his father, a wool trader. When Ford was two years old his parents were divorced because of abuse. His mother, Dorothy Gardner King, moved to Grand Rapids, Michigan. There she met and married Gerald R. Ford, owner of a small paint factory. Ford adopted her son, and the boy's name was changed to Gerald R. Ford, Jr. Gerald Ford, Sr., described by biographers as a dominant athletic man and strong believer in self-discipline, later fathered three sons. He never told young Gerald that he was adopted until years later.

At South High School in Grand Rapids, the younger Ford was all-city football center for three years and also made the all-state team. He played football career at the University of Michigan; in 1934 he was the Wolverines' most valuable member. He graduated in 1935 with a bachelor of arts degree. Ford declined bids from professional football teams in order to attend Yale Law School. He alternated semesters at study with work as an assistant football and freshman boxing coach. Ford graduated in 1941 in the top third of his class and returned to Grand Rapids to practice law.

In 1942 he joined the Navy as an ensign. He served 47 months, including 18 months aboard the light aircraft carrier USS Monterey in the South Pacific. He served as athletic director, then gunnery division officer, an assistant navigator with major operations in the South Pacific, and then a lieutenant commander. He encountered a near death experience in December 1944 during a vicious typhoon. He came close to being swept overboard from his ship. After the war was over in 1946 he returned to his law firm in Grand Rapids.

Three weeks before his first election, on Oct. 15, 1948, Ford married Elizabeth "Betty" Bloomer, a former model and aspiring dancer. Born in Chicago, she had lived most of her life in Grand Rapids and had been married and divorced. Jerry and Betty Ford had three sons and a daughter. She became a vocal and effective spokeswoman for important social and women's issues during and after her years in the White House, appearing somewhat less conservative than Ford himself.[2]

Congressional career

Both his father, a Republican leader in Grand Rapids, and the late Republican Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg urged young Ford to run for Congress. Vandenberg, who was an internationalist, wanted to oust the isolationist Republican congressman from the Grand Rapids area district, Bartel Jonkman. Ford won the primary, defeating incumbent Congressman Bartel J. Jonkman by more than 9,000 votes and went on to an easy victory in the general election. At this stage his basic political outlook was influenced by Wendell Willkie, by service in World War II, and by hostility to the dominant local machine. Ford ran as a minority reformer. Ford's view of himself as a minority reformer willing to stand up and oppose what he saw as corruption.[3]In 1949, the year he entered Congress, Ford was selected by the U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce as one of the country's ten outstanding young men. Ford's rise in the House was steady, assured by his repeated reelection from the strongly Republican district in a conservative region.

Communism and ideological subversion

After two years in the House, Ford won a seat on the powerful House Appropriations Committee and soon became the top Republican on its defense subcommittee. He became an expert on defense and military affairs and emerged as a strong anti-Soviet hawk in the Cold War years. Ford headed a group of 15 House Republicans who produced an exhaustive study endorsing the Cold War policies of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

However, Ford voted on July 27, 1953 against the congressional re-enactment of a House select committee to investigate subversion among tax-exempt organizations.[4] The committee in the previous Congress was headed by Georgia Democrat segregationist Edward E. Cox, who conducted a poor investigation and released insufficient findings.[5] Advocating for its re-approval during the 83rd Congress was Tennessee conservative Republican B. Carroll Reece, who became the chairman. It was thus known as the Reece Committee.

House leader

In 1961, Ford became chairman of the House Republican Conference, making him the third most powerful Republican in the House of Representatives.

In 1963 Ford took over as chairman of the House Republican Caucus. Two years later, with the help of young Turk House colleagues Melvin Laird of Wisconsin, Robert Griffin of Michigan, and Charles Goodell of New York, Ford became House Minority Leader, ousting incumbent Charles Halleck of Indiana by a 73-67 vote.[6] His weekly press conferences with Everett Dirksen, the GOP Senate leader, made them the national voice of the Republican party. He supported Kennedy and Johnson's involvement in the Vietnam War.

Warren Commission appointment

Ford was appointed by the new president Lyndon B. Johnson in 1963 to the Warren Commission, which investigated the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Ford was known to have changed autopsy reports regarding JFK's assassination, changing notes to "clarify meaning", in his own words.[7] Despite his own claims of only intending "to be more precise", it is apparent that Ford intentionally changed the reports to support the single bullet theory.[8]

Tenure

Domestically, he was consistently conservative, and led the fight against Johnson's Great Society. As long as the Conservative Coalition was intact he usually won; Johnson's landslide in 1964 over Barry Goldwater brought in scores of new Democrats and opened the door for liberal legislation and Ford was usually on the losing side. Ford's conservatism was endorsed by the voters in 1966, as the New Deal Coalition started unraveling because of voter disgust with Johnson's inept handling of the Vietnam war and the violent outbreaks in large American cities.

Ideologically Ford was flexible. He once described himself as "a moderate in domestic affairs, an internationalist in foreign affairs, and a conservative in fiscal policy." Ford had a good television persona, which he needed as the main spokesman for his party. He showed a knack for wooing more liberal congressmen, especially within his own party. His easygoing amiability made him widely popular. Ford's leadership of an effort in 1970 to impeach liberal Supreme court Justice William O. Douglas was attributed to soldierly loyalty to the White House. Ford had harbored only one further ambition - to become speaker of the House - but he became discouraged when the Republican Party could not gain a majority.

Vice-President

In October 1973, Vice-President Spiro T. Agnew resigned in the wake of disclosures that he had accepted illegal bribes. President Nixon, empowered by the 25th Amendment to nominate a successor, was said to favor John Connally, former secretary of the treasury. But, Laird, then a White House adviser, convinced Nixon that Connally would be unacceptable to Congress, which had to confirm the nomination, and recommended Ford. Nixon nominated Ford on Oct. 12, 1973. Ford then underwent an intensive investigation of his personal life by the FBI and by Congress.[9] Charges by a lobbyist that Ford had done political favors for contributors were found to be fabricated. Ford was confirmed by Congress and was sworn in as vice-president on Dec. 6, 1973.

As vice-president, Ford called inflation "Public Enemy Number One," promoted the "WIN: Whip Inflation Now" slogan, and urged budget cuts. He was an ardent foe of busing to achieve racial integration. He repeatedly defended President Nixon's innocence in the Watergate affair and its cover-up. Ford dropped that defense only when Nixon, on August 5, 1974, released tapes that showed his complicity in the cover-up and made his impeachment and conviction inevitable. Nixon then resigned, and Ford became president on Aug. 9, 1974.

Presidency (1974–1977)

Gerald R. Ford took the oath of office as President of the United States on August 9, 1974. Responding to the Watergate affair, he focused his inaugural address on integrity. If you have not chosen me by secret ballot, neither have I gained office by any secret promises. I have not campaigned either for the Presidency or the Vice Presidency. I have not subscribed to any partisan platform. I am indebted to no man, and only to one woman--my dear wife--as I begin this very difficult job.

My fellow Americans, our long national nightmare is over."[10]

By telling the American people that he was "a Ford, not a Lincoln," he not only lowered public expectations about what he might accomplish, he also reassured the American people that the days of the imperial presidency in the style of Johnson and Nixon had ended.

Administration

| Office | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| President | Gerald Ford | 1974-1977 |

| Vice President | Nelson Rockefeller | 1974-1977 |

| Secretary of State | Henry Kissinger | 1974-1977 |

| Secretary of Treasury | William E. Simon | 1974-1977 |

| Secretary of Defense | James R. Schlesinger | 1974-1975 |

| Donald Rumsfeld | 1975-1977 | |

| Attorney General | William Saxbe | 1974-1975 |

| Edward Levi | 1975-1977 | |

| Secretary of Interior | Rogers Morton | 1974–1975 |

| Stanley K. Hathaway | 1975 | |

| Thomas S. Kleppe | 1975-1977 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Earl Butz | 1974-1976 |

| John Albert Knebel | 1976-1977 | |

| Secretary of Commerce | Frederick B. Dent | 1974-1975 |

| Rogers Morton | 1975 | |

| Elliot Richardson | 1975-1977 | |

| Secretary of Labor | Peter J. Brennan | 1974-1975 |

| John Thomas Dunlop | 1975–1976 | |

| William Usery, Jr. | 1976-1977 | |

| Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare | Caspar Weinberger | 1974–1975 |

| F. David Mathews | 1975–1977 | |

| Secretary of Housing and Urban Development | James Thomas Lynn | 1974–1975 |

| Carla Anderson Hills | 1975-1977 | |

| Secretary of Transportation | Claude Brinegar | 1974–1975 |

| William Thaddeus Coleman, Jr. | 1975–1977 |

Ford kept some of the original cabinet members from Nixon's Presidency, such as Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. He replaced Nixon's Secretary of Defense, Secretary of Commerce and Attorney General would resign. He chose liberal Republican Nelson Rockefeller, governor of New York, as his Vice President. After a bruising hearing. Rockefeller was confirmed in December 1974, over the opposition of some conservatives like Barry Goldwater. Rockefeller was ineffective and unhappy in the new role.[11]

In the "Sunday Morning Massacre" of November 2, 1975, Ford replaced Kissinger as National Security adviser (but kept him as secretary of state) with Brent Scowcroft; fired Defense Secretary James Schlesinger, a leftover from the Nixon administration whom Ford personally disliked, and replaced him with his chief-of-staff Donald Rumsfeld; replaced another Nixon appointee, CIA Director William Colby, with George H. W. Bush, the ambassador to China; and informed Vice President Rockefeller that he would be dropped from the ticket in 1976.

Pardon

Ford's honeymoon suddenly ended on September 8, 1974, when he gave Nixon an unconditional pardon for all federal crimes he might have committed in office. The timing was bad, and the Democrats had an issue they used to score massive gains in the November Congressional elections.[12] The Watergate tragedy had dragged on for two years and grievously undermined public confidence in core national institutions, as both the president and vice president, and many top aides, had been forced to resign. Many went to prison. Ford's role was to start fresh again, but the pardon cost him desperately needed momentum. He handled the pardon issue maladroitly, failing even to insist that Nixon give up his presidential papers and tapes or issue a statement of contrition before granting him a pardon, and timing it just before the midterm elections, allowing it to do maximum damage to the GOP candidates.

Ford was the target of two unsuccessful assassination attempts. One in Sacramento, California on September 5, 1975 was attempted by Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme. Then in San Francisco, Sara Jane Moore pointed a pistol at him, but a bystander grabbed the gun.[13]

Economy

Ford's vision for America were grounded in conservative principles that emphasized fiscal responsibility, decreased federal involvement in the economy, lower taxes, and long-term sustainable growth with low inflation. Rampant inflation was the economic terror of the 1970s, and its reduction was Ford's overriding domestic priority. But growth rates were also low—the combination was new and unexpected and was called "stagflation." Mus of the problem came from international economic trends, as oil prices skyrocketed and Japanese and German imports for the first time became major threats to American factories.Ford's favored means for combating inflation was the conservative stand-by: a combination of fiscal austerity and a tight federal monetary policy. He attacked the heavily Democratic 94th Congress for wasteful spending, and 66 times wielded the presidential veto to kill costly congressional bills. His refusal to help New York City's financial crisis was briefly popular in the hinterland.[14]

The weak economy was a major concern during the Ford administration. Inflation was in the double digits, unemployment was rising and the gross domestic product was in decline.[15] Ford proposed a tight lid of $300 billion on the federal budget and asked for a $5 billion surtax (additional income tax) on corporations and families in the higher income bracket. These were part of his "whip inflation now" (WIN) program; they proved ineffective.

Ford fought constantly with Congress, especially when Democrats made major gains after attacking his pardon in the 1974 elections. Sixty-six times he exercised his veto power. Congressional Quarterly reported that Ford won only 58% of congressional votes that he took a position on, the lowest level of support from any president. Ford's press secretary, Ron Nessen, was incompetent and repeatedly blamed the news media for reporting on Ford's failures.

Oil prices were also a major concern. Congress turned down Ford's proposals for phasing out the federal ceilings on the price of most domestic oil. Senate Majority Whip, the Exalted Cyclops Robert Byrd (D-West Virginia) explained why Democrats rejected Ford's plans: "After all, he doesn't have a national constituency, his is an inherited Presidency." Ford and Congressional Democrats finally reached a compromise with the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975. "Half a loaf was better then none, so I decided to sign it," Ford explained.

The initial goodwill toward Ford steadily eroded as the numbers turned sour. Unemployment went from 4.8% in 1972 to 8.0% when he took office; consumer price inflation jumped from 3.4% to 11.0%. Unexpectedly high inflation, fueled by soaring oil prices, made it difficult to plan for the future; cheap imports from Germany and Japan for the first time became a threat to autos and electronics; high unemployment troubled industrial areas. By early 1975 the jobless rate was the worst since the Great Depression. Ford insisted that inflation was the greater problem. He sought to slow it, as Nixon had, by severe restraints on government spending for social programs. He also tried to curb private spending by asking Congress to raise the taxes on personal incomes. But the Democratic majority refused, and in congressional elections in November 1974 Democrats increased their majorities to three-fifths in the Senate and two-thirds in the House. In January 1975 Ford finally yielded to liberals' demands for a program to stop the economic slump and promote hiring. He proposed personal income tax rebates, especially to higher-income people, who might spend extra money on durable goods such as automobiles. Liberals criticized Ford's proposal for offering little relief for the poor, so they pushed through Congress a modified, though modest, tax rebate bill favoring lower-income people. Ford signed it reluctantly. He continued to resist liberal demands for massive public works spending to employ the jobless, and vetoed many bills.

Ford also wanted to make the domestic energy industry more profitable, even at the cost of inflation, in order to encourage more private investment in it and thereby reduce the dependence on oil from abroad. He proposed huge public subsidies for developing new energy sources.

Deregulation - that is, the removal of the old New Deal controls on transportation, communications, finance and other businesses - began under Ford (Nixon was more of a New Dealer who liked federal regulations), and continued under Carter and Reagan until most of the New Deal controls on business had ended.

Supreme Court

When an opening occurred in the Supreme Court in 1975, Ford was determined to use the appointment not as a vehicle for his own political or ideological goals, but to help restore confidence in government. He did this by placing a premium on professional considerations and relying on his attorney general, Edward Levi.

Ford nominated Circuit Judge John Paul Stevens as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court in 1975 to replace Justice William O. Douglas, who had recently retired. Stevens was unanimously confirmed in December. In nominating John Paul Stevens, Ford chose someone he saw as a nonpolitical choice, someone he could allow independence from White House supervision, and someone who reflected a non-ideological, nonpartisan selection process, although Stevens over the years emerged as the most liberal justice, though less so than Douglas, who was one of the last new Dealers in power.[16]

Foreign policy

On November 23, 1974, President Ford and Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev reached an agreement by signing the SALT treaty, which froze the number of strategic ballistic missile launchers at existing levels.

Vietnam

Ford blamed Congress for Communist North Vietnam's conquest of American ally South Vietnam in April 1975, because it had banned the renewed use of U.S. military forces there and refused his request for more aid to the crumbling resistance.

Historians are sharply critical of Ford's handling of the Mayaguez incident in which fifteen Marines were killed and eight helicopters downed. They were rescuing the crew of the merchant ship Mayageuz, captured by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia when the ship allegedly sailed into Cambodian waters. More American rescuers died than crewmen were saved.

In 1975-1976 Ford sanctioned secret U.S. aid to the anti-Soviet factions in the civil war in Angola, which ended in a leftist victory.

1976 Reelection Campaign

For a more detailed treatment, see United States presidential election, 1976.

By late 1976 the United States was not involved in any war, but the détente policy was rapidly losing political support, with Kissinger a scapegoat. Inflation had moderated. Business had recovered from the deep slump, though unemployment was still high.

Ford, after overcoming a strong challenge for the Republican nomination from conservative Ronald Reagan, replaced liberal Rockefeller with conservative Senator Robert Dole of Kansas, as his running mate. He campaigned on his record of having blocked expensive social programs and thereby slowed inflation. Ford-the-insider was challenged by a complete outsider, Jimmy Carter, a former Georgia governor who promised to restore trust in government, reduce unemployment, and shrink the federal bureaucracy. Ford accused Carter of being fuzzy on issues and of lacking experience in foreign affairs. However he agreed to nationally televised debates - the first between presidential candidates since 1960 and in one debate Ford blundered badly by insisting falsely that "there is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe." Although Carter was expected to win easily, Ford almost wiped out his lead by the end of the campaign. Carter won on November 2, narrowly defeating Ford 50%-48%. Ford is the only president who never won a national election. Carter paid tribute to Ford in his inaugural address. "For myself and for our Nation, I want to thank my predecessor for all he has done to heal our land."

Historians generally agree with the verdict: the Ford presidency showed indecisive leadership, repeated political miscalculation, poor judgment, and lack of vision.

Post-Presidency

Ford attended the annual Public Policy Week Conferences of the American Enterprise Institute, and in 1982 established the AEI World Forum, which was a gathering of international former and current world leaders to discuss political and business policies. On August 11, 1999, President Bill Clinton awarded Ford the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nations highest civilian honor.[17] In 2001, Ford was also awarded the Profiles in Courage Award. After the 2000 Presidential election, he and his former rival Jimmy Carter co-chaired the National Commission on Federal Election Reform.[18]

President Ford died on December 26, 2006 at his home in Rancho Mirage, California due to arteriosclerotic cerebrovascular disease. Ford was 93 years old. President Ford's body was taken to Eisenhower Medical Center where it remained until the start of State Funeral Services.

Trivia

- The 1976 Presidential Election was the only campaign Gerald Ford had ever lost.

- Gerald Ford is the only President to serve in office with out having been elected to the Presidency or Vice Presidency.

- Ford was the longest-lived president in U.S. history, living to age 93, until George H.W. Bush surpassed him at age 94.

- He was the only President to have been an Eagle Scout.

Notes

- ↑ Watkins, William J. (July 29, 2019). How a misstep can shape the Supreme Court. The Washington Times. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ↑ Maryanne Borrelli, "Competing Conceptions of the First Ladyship: Public Responses to Betty Ford's 60 Minutes Interview." Presidential Studies Quarterly 2001 31(3): 397-414. ISSN 0360-4918.

- ↑ William A. Syers, "The Political Beginnings of Gerald R. Ford: Anti-bossism, Internationalism, and the Congressional Campaign of 1948." Presidential Studies Quarterly 1990 20(1): 127-142. ISSN 0360-4918.

- ↑ H RES 217. RESOLUTION CREATING A SPECIAL COMMITTEE TO CON- DUCT A FULL AND COMPLETE INVESTIGATION AND STUDY OF EDUCA- TIONAL AND PHILANTHROPIC FOUNDATIONS AND OTHER COMPARABLE ORGANIZATIONS WHICH ARE EXEMPT FROM FED. INCOME TAXATION.. GovTrack.us. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ↑ FascinatingPolitics (December 22, 2019). The Reece Committee on Foundations: Conspiratorial Nonsense or an Expose of a Threat to the Nation?. Mad Politics: The Bizarre, Fascinating, and Unknown of American Political History. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ↑ Wildstein, David (August 27, 2019). Another Frelinghuysen story. New Jersey Globe. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ↑ Gerald Ford forced to admit the Warren Report fictionalized

- ↑ Gerald Ford's Terrible Fiction

- ↑ A microscopic audit of his taxes showed only one mistake - he had deducted the cost of renting a tuxedo for inauguration ceremonies.

- ↑ http://www.ford.utexas.edu/LIBRARY/speeches/740001.htm

- ↑ http://205.188.238.109/time/magazine/article/0,9171,917422,00.html

- ↑ Soon after, Ford offered Vietnam War military deserters and draft dodgers a conditional amnesty, with penalties. Most war resisters in exile ignored the offer.

- ↑ Both were sentenced to life in prison, but Moore was paroled on December 31, 2007. report

- ↑ Yanek Mieczkowski, Gerald Ford And The Challenges Of The 1970s (2005).

- ↑ Henry F. Graff, "Gerald R. Ford," The Presidents, P. 538

- ↑ David M. O'Brien, "The Politics of Professionalism: President Gerald R. Ford's Appointment of Justice John Paul Stevens." Presidential Studies Quarterly (1991) 21(1): 103-126. ISSN 0360-4918.

- ↑ http://www.ford.utexas.edu/avproj/post-presidential.asp

- ↑ http://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/grf/timeline.asp#post

References

- Abramowitz, Alan I. "The Impact of a Presidential Debate on Voter Rationality, " American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Aug., 1978), pp. 680–690, advanced analysis of debate with Carter on unemployment, showing voters shifter their opinion to agree with Ford or Carter. in JSTOR

- Brinkley, Douglas. Gerald R. Ford (2007), short biography by scholar excerpt and text search

- Cannon, James. Time and Chance: Gerald Ford's Appointment With History (1998), 528pp; the major biography

- Greene, John Robert. The Presidency of Gerald R. Ford (1995), 272pp, the standard scholarly survey. excerpt and text search

- Greene, John Robert. The Limits of Power: The Nixon and Ford Administrations (1992)

- Greene, John Robert. Betty Ford: Candor And Courage In The White House (2004) excerpt and text search

- Hayes, Stephen F. Cheney: The Untold Story of America's Most Powerful and Controversial Vice President (2007). pp 70–122 on role as senior aide to Ford; excerpt and text search

- Mieczkowski, Yanek. Gerald Ford And The Challenges Of The 1970s (2005), 455pp; excerpt and text search

- Schapsmeier, Edward L. and Frederick H. Schapsmeier. Gerald R. Ford's Date With Destiny: A Political Biography (1989), strongest on Congressional years.

- Suri, Jeremi. Henry Kissinger and the American Century (2007)

- Werth, Barry. 31 Days: Gerald Ford, the Nixon Pardon and A Government in Crisis (2007), 416pp

Primary sources

- Council of Economic Advisors, Economic Report of the President (annual 1947- ), complete series online; important analysis of current trends and policies, plus statistcial tables

- Ford, Gerald R. A time to heal: the autobiography of Gerald R. Ford (1979)

- Greenspan, Alan. The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (2007), memoir by senior economics advisor

- Kissinger, Henry. Years of Renewal (2000). 1152pp; in-depth memoirs of the Ford years; excerpt and text search

- Zelikow, Philip. "The Statesman in Winter: Kissinger on the Ford Years" Foreign Affairs (1999) 78(3): 123–128. Issn: 0015-7120 Fulltext: Ebsco

- Laird, Melvin R. "A Strong Start in a Difficult Decade: Defense Policy in the Nixon-Ford Years." International Security (1985) 10(2): 5-26. Issn: 0162-2889 Fulltext: in Jstor

See also

- Gerald Ford's 1976 Republican National Convention Speech

- Conservative Coalition

- Henry Kissinger

- Richard M. Nixon

External links

- Gerald R. Ford Foundation

- Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum

- Works by Gerald Ford - text and free audio - LibriVox

| |||||

| |||||